York in American History: Invasive species in York’s history

Note: Invasive plant species are rapidly becoming a significant problem in York as it is in nearly all communities. The article presents illustrative cases from the historical record of non-native (invasive) plants and insect infestations that once ravaged the town and state and how these menaces were addressed.

"...The plant grows in patches, matting the ground and killing all other vegetation. Its rank growth and rapid spreading show that it flourishes in Maine climate and soil… It spreads by runners both above and under the ground, thus extending the patches…"

Cautionary words from Charles D. Woods, related to the first appearance in the state of an invasive plant known as King Devil Weed, which had been brought here from Europe.

The notice, published in the July 16, 1897, York Courant, 126 years ago, could be just as readily applied to Japanese knotweed, an invasive plant with distinctive features that can be readily identified as growing throughout this town at the present moment. Knotweed outcompetes all other vegetation by blocking the sunlight, spreads rapidly, and extends its growth using the so-called runners, or more correctly rhizomes, a horizontal root system that can be broken into tiny fragments and be sufficient to give rise to a fully developed plant. Seed dispersal is rare.

The rhizomes split when disturbed, and each fragment can form a fully functional clone of the parent plant. Fragments are often disseminated along waterways during flooding events or by the movement of soil containing root fragments. New plants can also form from stem fragments when in contact with moist soil. This vegetative spread makes established Japanese knotweed populations extremely difficult to control, as suggested by the Brandywine Conservancy.

Invasive plants of any kind jeopardize biodiversity, and not only in terms of plants but also in other forms of life associated with the plants. But Knotweed, which is aggressive in its growth, can also inflict significant damage by its strength, breaking through cracks in paved surfaces. Strangely, like the story of so many invasives, knotweed begins somewhat innocuously in the nineteenth century, being brought into geographically remote sites from a place of origin.

York in American History: How Dr. Emily Blackwell made history as a woman physician

It would seem the critical event in the story involved a man named Philipp von Siebold, who on August 9, 1850, had shipped a box of 40 oriental plant specimens to Kew Gardens in London. In Britain, where knotweed has developed into a significant environmental threat, the pervasive growth throughout the country can all be traced back genetically to Siebold's specimen.

This botanical monster was let loose upon the world deliberately, as an exotic thought to have potential as an ornamental plant, and it was even thought to have practical application, placed at riverbanks to diminish the chance of erosion. But, because it thrives where there are no predators to maintain control naturally, it can spread without any resistance and kill the native plants that are unfortunate enough to stand in its way.

In Japan, the plant is called itadori. It inhabits the extreme conditions found on volcanic slopes, and after an eruption, it can be the first sign of the recovery of organic life.

This is the background of a plant that has so many advantages outside of its native environment, because there are no insect predators to maintain control, and native plants are hardly a match for its unique qualities of adaptation to extreme conditions. Once you recognize it from an illustration, you will soon realize that it is everywhere around you.

York in American History: How a wealthy minority tried to split up the historic community

Invasive plants are not the only problem that this town has to deal with. Invasive insect pests are also a serious threat. Consider the brown-tail moth, originally from Europe. In 1897, as the warnings against King Devil Weed were being sounded, in the area around Somerville, Massachusetts, near Boston, an infestation of brown tail moths was documented. In the beginning, a relatively small area was involved, but within three years, the area of the moth's domain had extended as far north as Canada and into most of the New England states.

By March 1908 and the annual town meeting, the moths had reached a crisis here. Article 30 reads, "To see if the town will vote to appropriate a sum of money for the destruction of brown tail moths." Simultaneously, Spongy Moths, formerly called European gypsy moths, also had to be dealt with. The Report of Maine's Agricultural Commissioner for that year said of York, "this is the worst town of all as far as the gypsy moth is concerned."

Included in the report is a photo of a tree in York upon which were found 1034 egg clusters, "a record in the state," according to the report. Now multiply this number by many hundreds, and the crisis this town faced becomes obvious.

This time we can look to an expatriate Frenchman, Etienne Trouvelot, who intending to create a resilient silkworm, brought the gypsy moths from Europe to his Medford, Massachusetts, home during the late 1860s. Some of the insects inevitably escaped, and the era of their reign of terror was opened. The caterpillars strip foliage from the trees and are endowed with special attributes that enable them to be carried by the wind from tree to tree.

In an intensive effort to contend with the menace, which it should be noted involved not only York but all of the contiguous towns, different strategies were employed. Over 16,000 egg clusters were located and destroyed and 77,000 caterpillars were killed. The scale of the problem faced by this town is also revealed: "83 infestations in York, 80 being in orchards and 3 in the woodland."

Consider what was encountered at Henry Moulton's, "the worst infestation ever found in the State of Maine." The entire thirty acres of the property had been effected, "here was found 5,001 egg clusters in the stone walls, board piles, and the trees. In July of 1907, at the A. Thompson property in Cape Neddick, large numbers of caterpillars were observed crossing the road. This was another of the worst local infestations.

When we know something of the damage caused by these pests, the final chapter in George Ernst's book, "New England Miniature: A History of York, Maine," may possess a deeper meaning. Ernst gave this the title "A Modern Miracle" and it describes how an unusual natural event at the end of December 1914 decimated the populations of brown-tailed moth caterpillars, effectively freeing York for several years.

In 1914, the problem had been especially severe, so that by June, "the trees looked as bare as they had in winter." Next, he noted, as the caterpillars went through the transformation into moths, "the air was white with them." Then, shortly after Christmas, the cold weather was interrupted by a thaw of several days. The caterpillars appeared as if conditions were ideal for them. But the unusually warm temperatures were followed by extreme cold, below-freezing temperatures. "Every last insect was killed in this one action." Such was the modern miracle.

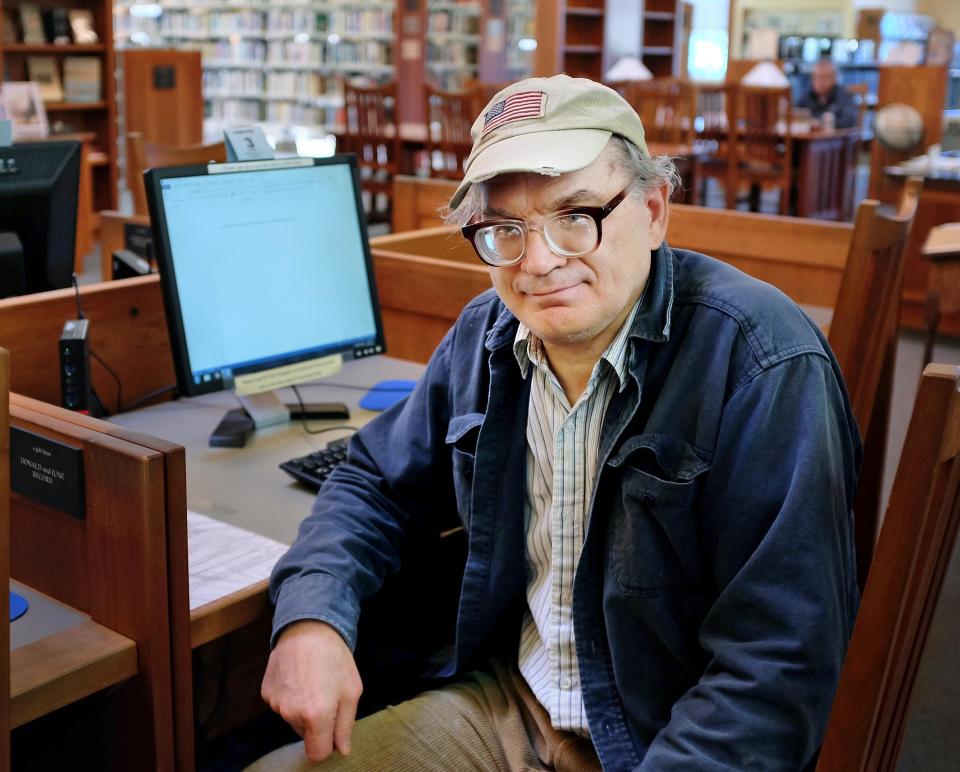

James Kences is the town historian for the town of York.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: York in American History: Invasive species in York’s history