York County’s position on Mason-Dixon Line muddies sense of identity

(This is the first of a series of occasional columns about York County and its relationship with the Mason-Dixon Line. The second column will be published on April 16.)

If parts of York County’s story are new to those in the OLLI at Penn State York classes that I teach, then they likely aren’t widely known.

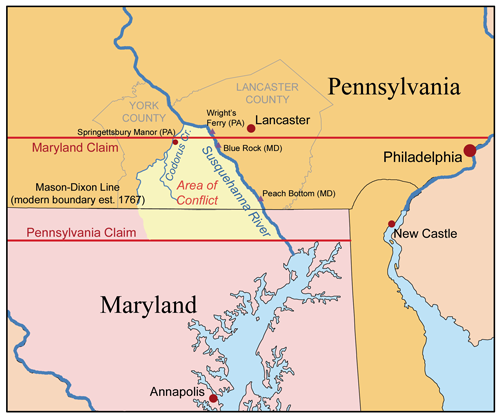

I’ve found those 50-plus-year-old students really are on top of things, so I decided to check their knowledge about the Mason-Dixon Line in the recent class “What makes York County, York County.” That line that separates Maryland and Pennsylvania and North from South, of course, also defines the county’s southern boundary.

So here’s one question I posed: How many miles of York County border did Mason and Dixon survey in 1765, considering that the total boundary was 233 miles long?

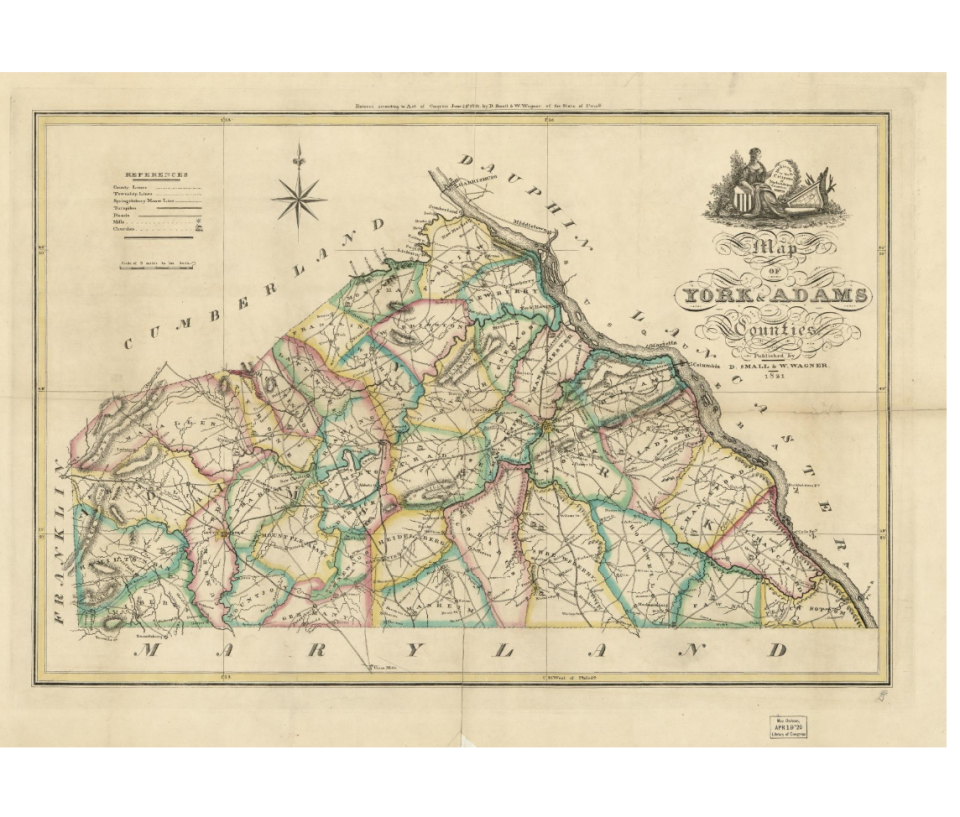

That proved to be a tough one for this class and likely for most people. The answer is 65 miles or 28% of the line before 1800 and 45 miles or about 19% after Adams County separated in that year.

Those are both large swaths and mean something: One might logically conclude the longer the border, the stronger the links with the South.

So that geographical kinship helps explain some of the “what and why” about York County, given our long border with the slave state of Maryland before 1865.

And then I asked the OLLI class about the length of the Mason-Dixon Line in Lancaster County. The answer surprised the 100 present, as it did for me when I first looked at it.

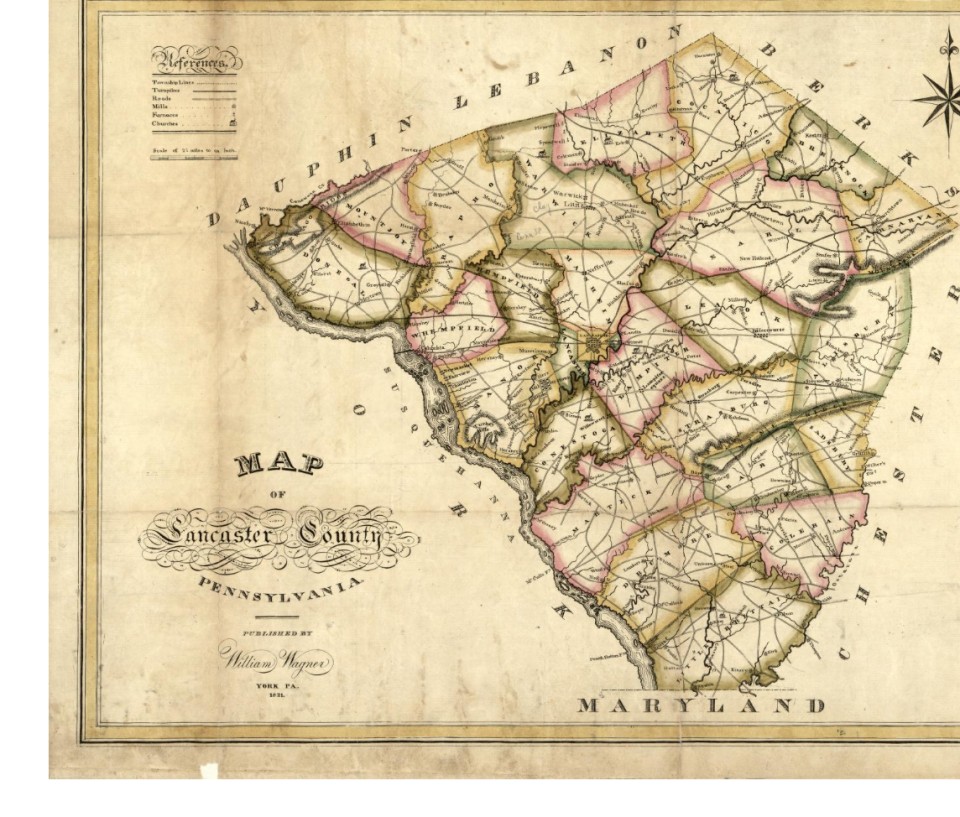

Lancaster County’s border with Maryland is just 6 miles or about 2.5% of the line.

So York County has a different story from Lancaster, with this wide variance in exposure to the South. This also might help answer a question that you’ll hear around the county: Why are there so many Confederate flags flying around here?

First county west of river

The milewide Susquehanna River shaped York County, too.

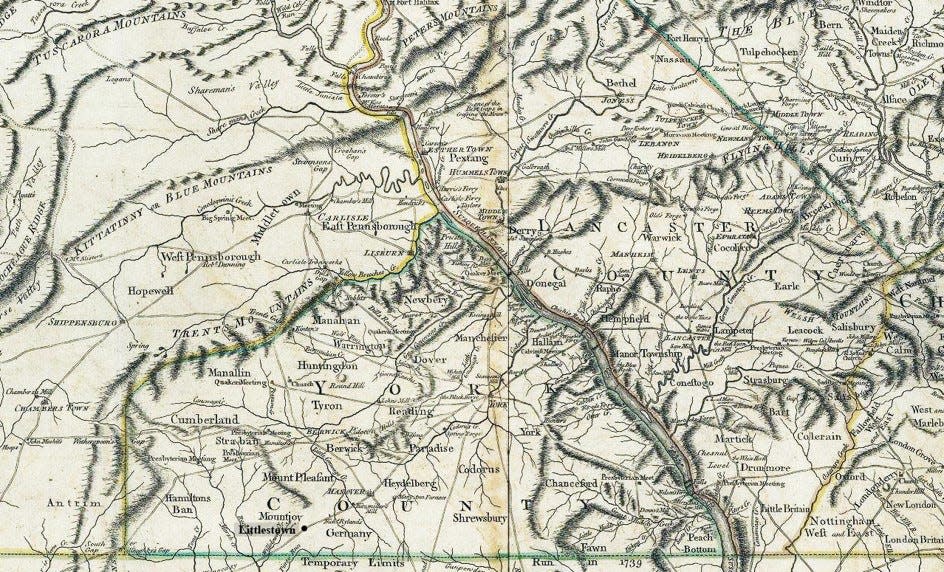

When European pioneers crossed the rocky river in numbers after about 1730, many settled on the frontier: future York County.

York was the first county west of the Susquehanna, separating from Lancaster in 1749 because it needed a sheriff and court system to address outbreaks of lawlessness in its 1,430 square miles.

The county sprawled “to the setting sun” as described in a Penn treaty with Native Americans. That actually meant South Mountain, 65 miles, as we’ve seen, from the Susquehanna.

Cumberland County, to York’s northwest, was formed in 1750, so York wasn’t entirely alone west of the mile-wide river. But as you head farther west, Franklin County formed in 1784, more than 50 years after those settlers started crossing. Dauphin County, to York’s north, was founded in 1785.

More:Strolling writer takes in York County and the region at 3 miles an hour

More:‘Endurance’ is apt title for York native’s latest book

So where could York County partner in the 1700s? The Susquehanna, between York and Lancaster, was not bridged until 1814. Settlers could cross on Wright’s Ferry, wait in line and pay a fee. If heading east, they faced a 70-mile journey to Philadelphia.

It was convenient to look south about 50 miles to Baltimore, a Southern port city since the early 1700s. In fact, some York County residents, particularly in today’s Hanover area, arrived from Maryland, different from most county residents who came here from Philadelphia and New Castle, Delaware.

York County’s geography always adds complexity to its story. Philadelphia wanted to trade with the fertile and well-watered York County. Historian Jo N. Hays has shown in a study covering 1800 to 1850 that York County merchants and residents bought things from Philadelphia and sold their goods in Baltimore.

Philadelphia competed with Maryland to secure York County as a market. Hays points out that Philadelphia backed the turnpike from Wrightsville to York, and Baltimore supported the toll road to York, both in 1810.

This research shows how economically blessed York County was — and is — to have such connections with these two major markets.

But in the minds of York County residents, a certain ambiguity set in.

They were Pennsylvanians, after all, and their state government and many important trade partners were in Philadelphia.

But they were somewhat sealed off by the Susquehanna, and their family, friends and customers for their distilled spirits and other farm products lived in Maryland and points south.

Did southern York County’s Civil War farmers working the soil along the long Mason-Dixon Line, differ in their views about equality of the races from their Maryland counterparts, owners of enslaved people? The invisible surveyor’s line was not designed to stop the racism that came with slavery.

C. Vann Woodward, in “The Burden of Southern History,” writes about Civil War-era Marylanders and others in slave states that remained in the Union as well as those in the southern parts of states that shared the border with the South. That would include Maryland, Pennsylvania and York County.

“… (A)nd many of their attitudes and habits were not very different from those to the southward,” he wrote, “Their enthusiasm for the third war aim (equality of the races) was a matter of some doubt.”

Was York a Northern county facing south? Or a Southern county looking north? Either way, York County residents, then and now, would struggle at times with Southern attitudes toward race.

Crown enters border dispute

A map in 1770 shows York as a popular crossroads, particularly in hosting traffic along the Great Wagon Road, connector of two great rivers: the Susquehanna with the Potomac. This road was the main feature of a corridor for settlers moving through today’s Wrightsville, York and Hanover to Frederick, Maryland, and then the Shenandoah Valley and points south.

Some put down shallow roots to farm for a spell in York County and later moved south. For those staying “a while” or longer, they were faced with another ambiguity about place.

For about 35 years after John Wright’s ferry opened in 1730, many settlers did not know whether they were farming under the Penn proprietorship in Philadelphia or Marylanders under the Calverts in Annapolis.

Maryland was claiming as far north as Long Level, then in Hellam Township, and then a straight line west. So would a Long Level settler live in Hellam, Pennsylvania, or Hellam, Maryland?

The Penns and Calverts held far different views of their property lines until the British Crown contracted with the surveying team of Mason and Dixon starting in 1763 to settle the heated dispute.

Hays, the historian, titles his essay “Overlapping Hinterlands,” with York County squarely in the overlap between Philadelphia and Baltimore’s markets.

Though relationships with both cities ebbed and flowed in the early 1800s, York’s kinship with Baltimore and the South accelerated with the laying of the Northern Central Railway connecting Baltimore and York about 1838, just in time for the buildup to the Civil War. Later, the Maryland and Pennsylvania and Western Maryland railroads would connect Baltimore and York.

Over time, York County would take on characteristics attributed to Baltimore: working class, grittiness, fond of King Syrup and liking Ocean City, Maryland, beaches. There was not enough educational muscle in the county to create a four-year college until about 1970, when York Junior College became York College.

Lancaster was influenced by Philadelphia, America’s largest city in the 1700s and filled with enough refinements and amenities to delight British officers in their occupation in 1777-78. And by the 1800s, Lancaster would host three colleges: Franklin & Marshall, Millersville and Elizabethtown.

The point about higher education is important. Until about 50 years ago, York County did not have a higher-education system to disrupt Southern thinking wafting across that long line.

York in the North or South?

People can easily overlook York County’s complexity and the array of influences coming its way. It’s in the Keystone State, linking the Northeast and Southeast. It’s the midmost of the Middle Atlantic states. In both cases, North meets South here.

Further, it’s in the North, a market long coveted by Philadelphia. It was almost in the South but for the work of Mason and Dixon.

Indeed, it was ground zero for the dispute that drew the surveyors here in the first place.

In the 1730s, Marylander Thomas Cresap lived on a large tract in Long Level and served as a propagandist for the Calverts and an advocate for the Maryland border running as far north as his land.

His acreage lay about 18 miles north of where the line eventually would run.

His tactics got him in trouble with Pennsylvania authorities, who smoked him out from his fort – his home. They transported him to prison in Philadelphia.

It is said the resolute Cresap admired Philadelphia, saying, “Dammit, this is one of the prettiest towns in Maryland.”

York County can thank Mason and Dixon for clearing up geographical confusion and for providing the physical size that contributed to a high national profile in agriculture and industry.

But that line has not cleared up York County’s identity — its sense of place — a point of ongoing struggle illustrated by those Confederate flags waving from houses and attached to vehicles.

The county has an ambiguity of place, common in border counties, that has caused us to falter at times: York surrendered to the invading Confederates, some of them Southern family and friends, in the days before the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. The county has a long history of racial discrimination that spawned late-1960s race riots and then delayed arrests for 30 years in murders coming from those revolts.

Work is underway on many fronts in helping county residents better understand the past, those times that our confusion about identity trumped judgment.

Neil King Jr., who walked through York County as part of a Washington, D.C.-to-Manhattan trek in 2021, laid out one path forward, noting “the memory boom” taking place in York County.

This movement is creating a deeper understanding of our past, he said in an interview, and hope for a “wise and more inclusive path forward.”

“That is so essential,” he said, “to the vitality of a place.”

Sources: YDR files, G.A. Mellander and Carl E. Hatch, "York County's Presidential Elections,” Jo N. Hays, “Overlapping Hinterlands: York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, 1800-1850,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1992.

Upcoming event

Neil King Jr., author of “American Ramble: A Walk of Memory and Renewal,” will discuss his book and impressions about his walk through York County at 5 p.m. April 11, at York College’s Center for Community Engagement, 59 E. Market St., York. “An American Rambles through the Heart of York County” is open to the public free of charge and co-sponsored by the center and Hometown History, a video/podcast series.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: York County’s position on Mason-Dixon Line muddies identity