From New York to Milburn, a piece of 9/11 finds a home in Oklahoma

You don't have to live in New York or a big city in Oklahoma to view artifacts from the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001.

Because of the efforts of Milburn High School's 2011 graduating class — all 11 students — a piece of a steel I-beam from one of the World Trade Towers is on permanent display in the Johnston County Courthouse on Main Street in Tishomingo.

But, apparently, not that many people remember the display, or know much about it.

"We have people in town who have no clue it's there," says Nellie Garone, the high school teacher who sponsored the students' efforts beginning in 2010 to bring the artifact to their small, southeastern Oklahoma town.

"I don't think it's well-known that it's there, which makes me sad," says Mike Whalen, 30, now living in Tishomingo. He was 9 years old when terrorists hit the two New York towers in hijacked commercial aircraft.

It was Whalen's idea to bring an artifact from the disaster to Milburn as their 2011 class legacy project. It was then moved to the courthouse so that more people can view it.

"I think the exhibit is important to 'physicalize' the tragedy that we saw on the news," Whalen said.

'Maybe it's a sign of healing'

Remembering the tragedy continues to inspire him, especially on difficult days.

"It reminds me of both the perseverance of a nation in turmoil and our class's determination to accomplish the goal," he said.

That people there don't remember the artifact doesn't mean they don't care, he said.

"The wound isn't as fresh as it was then. So, maybe it's a sign of healing that it's not as well known as it should be," he wrote in an email.

Kim Canady, the deputy court clerk of Johnston County, said, "I don't think people know it's here unless you've been here to pay your taxes, or go to court, or to file with the county clerk's office."

The pandemic can be blamed for some of the problem, she said.

"Since COVID, a lot more things are online now. I think that has slowed down the (foot) traffic," she said, while standing in the front entrance of the courthouse looking at the display just a few feet from her office.

The display — normally in the first floor foyer — sits by the entrance to the courthouse as interior walls are being painted and the floor is being re-tiled.

Marcus West, 30, the president of Milburn's 2011 senior class, says it probably doesn't make much difference where the I-beam is located but thinks the courthouse is a "good place for it."

It's only natural, he says, that a younger generation wouldn't know that much about the event because they didn't live through it.

"It's not relatable. It's just seen in the video or the date once a year. There's always going to be a little disconnect," West said. "In the world we live in, people have to go through something personally to be affected by it."

More: How many people died in 9/11? Firefighters, passengers and more who died 22 years ago.

Jason Bryant, a former fire chief and now the director of Emergency Management for Johnston County, passes by the display three to four times a week as he goes about his official business.

"I think it's pretty neat to have something like this here from New York all the way down to little Tishomingo, Oklahoma," he said.

As a former fireman, he said he is often reminded of the number of firefighters who died in New York.

"We had 343 firefighters die that day. One hundred ten flights of stairs. The dedication and everything that went into what those guys did. They didn't run. They ran into it, up to it. Not away from it," he said, while measuring the I-beam in the Plexiglas display case.

Bryant believes some good did come out of the tragedy.

Today's emergency responders, whether they are firefighters, paramedics or law enforcement, are all more efficient because of changes made to unify and streamline their services as they work together. Among the many changes, various agencies are finally using a unified code in order to better communicate with one another, he says.

Bryant likes that the display sits in the courthouse, even if some people use the top of the case as a desk to finish paperwork. He recalls that he saw an artifact from Pearl Harbor sitting in another courthouse, and it gives him a good feeling.

Sharing a special kinship between Oklahoma and New York

Originally designed to hold up a floor on one of the towers (it's not known which one), the I-beam is 28 inches tall, 15 inches wide and weighs at least 100 pounds. Getting it shipped to Milburn was a Herculean, community effort that still makes Garone shudder.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which had the authority to distribute the artifacts, rejected the students' efforts twice, which still miffs Garone, especially since chunks of beams — more than a thousand — have been distributed to all 50 states and several foreign countries.

Realizing that their application probably needed to be more sophisticated, Garone said the students became more persistent.

"We just decided, 'Dang it. We need to get this!'" Garone recalls.

The students researched how to write a persuasive letter in order to convince the Port Authority that an artifact from 9/11 belonged in their small community of barely more than 300 people at the time. They looked for more forceful adjectives to beef up their vocabulary, the teacher said.

The class emphasized that because of the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in 1995, everybody felt a special kinship between what happened in New York and what happened in Oklahoma City.

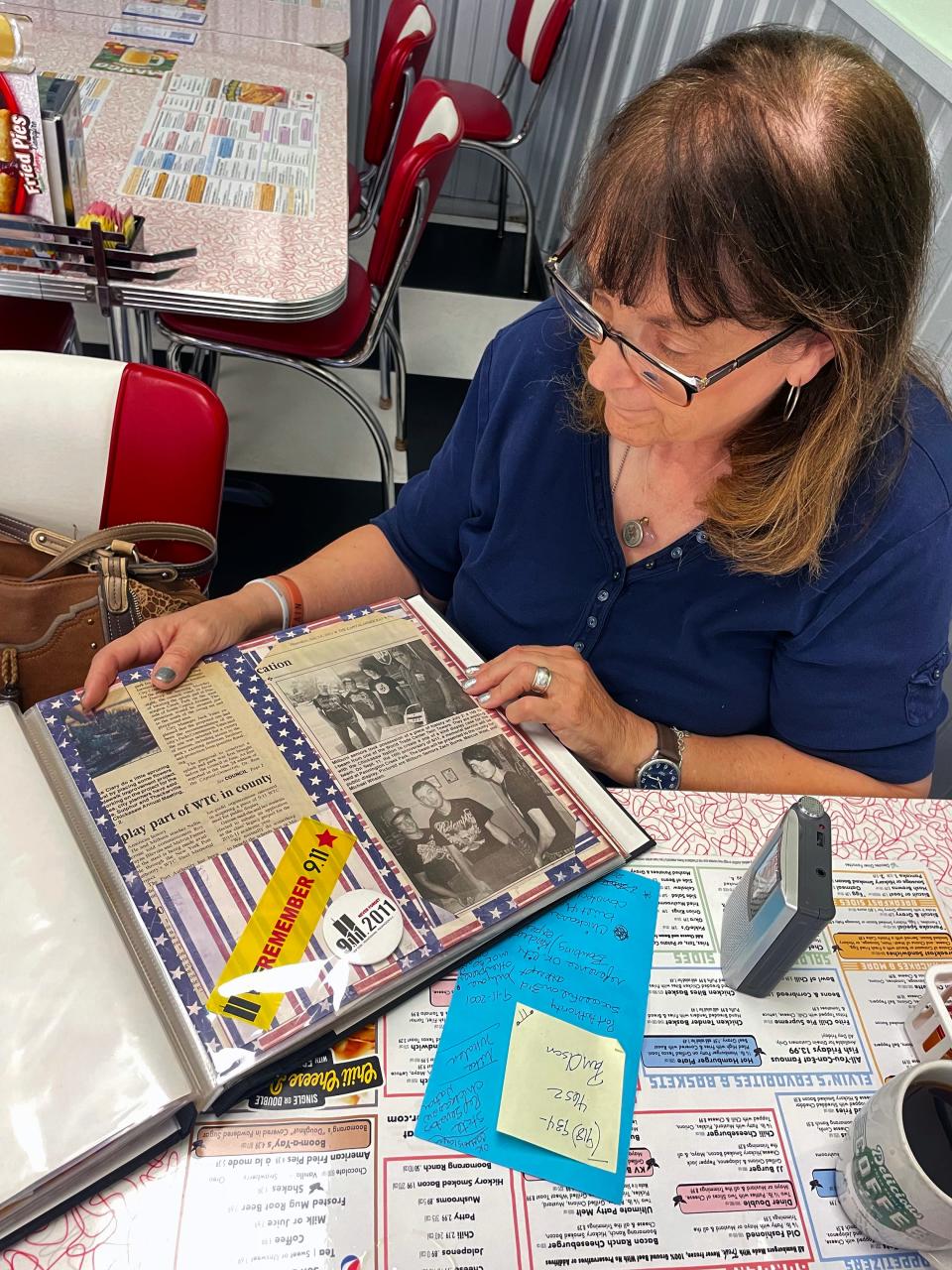

"We brought out all the big guns," Garone said as she sat in a local diner on Main Street in Tishomingo. Letters of support came from local leaders, elected state officials, county commissioners and the Chickasaw Nation, which constructed and donated a display case to protect the beam from vandalism.

On their third attempt, the Port Authority awarded them a chunk of the beam. Since then, the artifact has been on display in the foyer of the Johnston County Courthouse, 403 W Main, Tishomingo, which is open 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Mondays through Fridays.

People are welcome to come view it, says Canaday, the deputy county clerk.

"This is the people's house," she said.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Milburn High School class of 2011 brought piece of 9/11 to Oklahoma