A New York teacher was accused of raping a student at school. He went on to teach elsewhere

ROCHESTER, N.Y. – A 15-year-old girl walked into the music room at East High School in Rochester one afternoon in the spring of 1976 to fetch her guitar.

There, she says, her teacher grabbed her, pulled her into his office, shut and locked the door – and then raped her.

When he was done, he slapped her across the face and said "'Nobody’s going to find out about this, right?' I honestly don’t remember what I said to that," recalled the accuser.

In the coming months, the teacher would molest her dozens of times, said the woman, Betty.

A second woman, Laura, accuses the same teacher of locking her in that same office, for the first time when she was a shy sophomore in 1972. Over the next weeks and months, he groped and fondled her, over and over again.

The explosive allegations against the once-prominent music teacher, Edwin Davis Fleming, are laid out in lawsuits being filed by the two women under provisions of the Child Victims Act with additional details from face-to-face interviews.

It is the policy of the Democrat and Chronicle to not name victims of sexual assault without their consent. For the purposes of this story, the Democrat and Chronicle is calling the women Betty and Laura.

The lawsuits are seeking compensation from the school district and from Fleming, who is 87.

A reporter went to Fleming's South Carolina home. When he said he was there for the Democrat and Chronicle, Fleming said he had no comment and asked the reporter to leave.

Both women say the abuse they suffered at his hands has left them with lifelong psychological scars.

And it left them angry.

Betty says she reported Fleming’s actions to a top Rochester City School District administrator, Josephine Kehoe, two years after Betty graduated from East High in 1979.

Kehoe and two other officials familiar with the matter verified to the Democrat and Chronicle that the complaint was lodged, and one said it was passed up the chain of command as far as the superintendent of schools Laval Wilson.

But school district leaders allowed Fleming to walk out the door with his reputation unblemished and no police report filed. Kehoe, in a recent interview, said Fleming's dismissal was enough.

"She didn’t want it to become public. She just wanted to be sure no other girls were subjected to that," Kehoe said.

But Betty said she wanted more, and remains furious that Rochester school leaders did so little.

"It was like getting raped all over again," Betty said.

The Democrat and Chronicle has learned that Fleming went on to teach in a half-dozen local school districts – including the very same district where he’d been accused of preying on his students.

Quiet resignation

The case against Fleming highlights what once was a common response to such allegations – the quiet resignation, the practice of allowing an employee who is accused of sexual misconduct to slip quietly away while facing no consequences.

This practice is the heart of many of the 900-plus lawsuits that have been filed statewide under the Child Victims Act, which lets people seek justice and compensation for old child sexual abuse claims.

"It’s certainly a very, very common anecdotal refrain that we’re hearing in the Child Victims Act stories and that we’ve been hearing from victims for decades," said Deb Rosen, executive director of Bivona Child Advocacy Center. "Quiet resignations are just one example of the way that institutions chose not to control, expose or address inappropriate behavior. That allows inappropriate behavior to perpetuate and thrive."

Roman Catholic leaders, who are targeted in most of the Child Victims Act suits, became notorious for allowing sexually abusive priests to quietly leave one church and start work at another without any public acknowledgment of the priest’s abuse.

But the Child Victims Act docket is riddled with identical accusations against numerous other institutions, from the Boys Scouts to universities to public schools. The Democrat and Chronicle is being sued by a former paperboy.

Rochester is among 32 public school systems in New York to be named in such lawsuits since the act became effective three months ago. Most of those suits accuse school officials of failing to protect students from teachers, coaches, counselors or other school employees who were serial predators.

Almost all of those allegations are based on incidents in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s.

Awareness of the prevalence of child sexual abuse in educational settings grew beginning in the 1980s, and eventually reached the point that New York lawmakers stepped in. In 2000, the state Legislature passed a law requiring public school officials to report abuse cases, and explicitly forbidding them from accepting quiet resignations.

By then, it was too late for Betty.

'Debonair' or 'creepy'

Betty and Laura recently sat for an interview with a Democrat and Chronicle reporter in the office of their attorney, John Bansbach.

They were at first reluctant to speak and agreed to do so only if the newspaper promised not to publish their names and other information that might identify them.

The women, now within a few years of 60, had told virtually no one exactly what happened to them inside the confines of East High in Rochester. The courts have given permission for them to file their lawsuits using pseudonyms, BL Doe 1 and BL Doe 2.

BL Doe 1, or Betty, filed a legal complaint laying out her allegations against the school district and Fleming on Friday. The complaint for BL Doe 2, or Laura, is in preparation, Bansbach said.

Laura graduated from East High the year before Betty started and they did not know each other until they met through Bansbach. By coincidence, each of them had contacted Jeff Anderson & Associates, a nationally-known law firm that handles child sex abuse cases. That firm referred both to Bansbach.

During the emotional two-hour interview with the Democrat and Chronicle, the women shared their stories with a reporter and with each other. They seemed to find strength in the retelling and support in standing together.

It was the first time Betty allowed herself to speak aloud the words "I was raped."

Bansbach and Betty said they’ve heard of other possible victims of Fleming, though none have come forward.

Both Betty and Laura believe there were other girls who were exposed to the same abuse at Fleming’s hands.

"I can't imagine there weren't," Betty said.

Rising stars

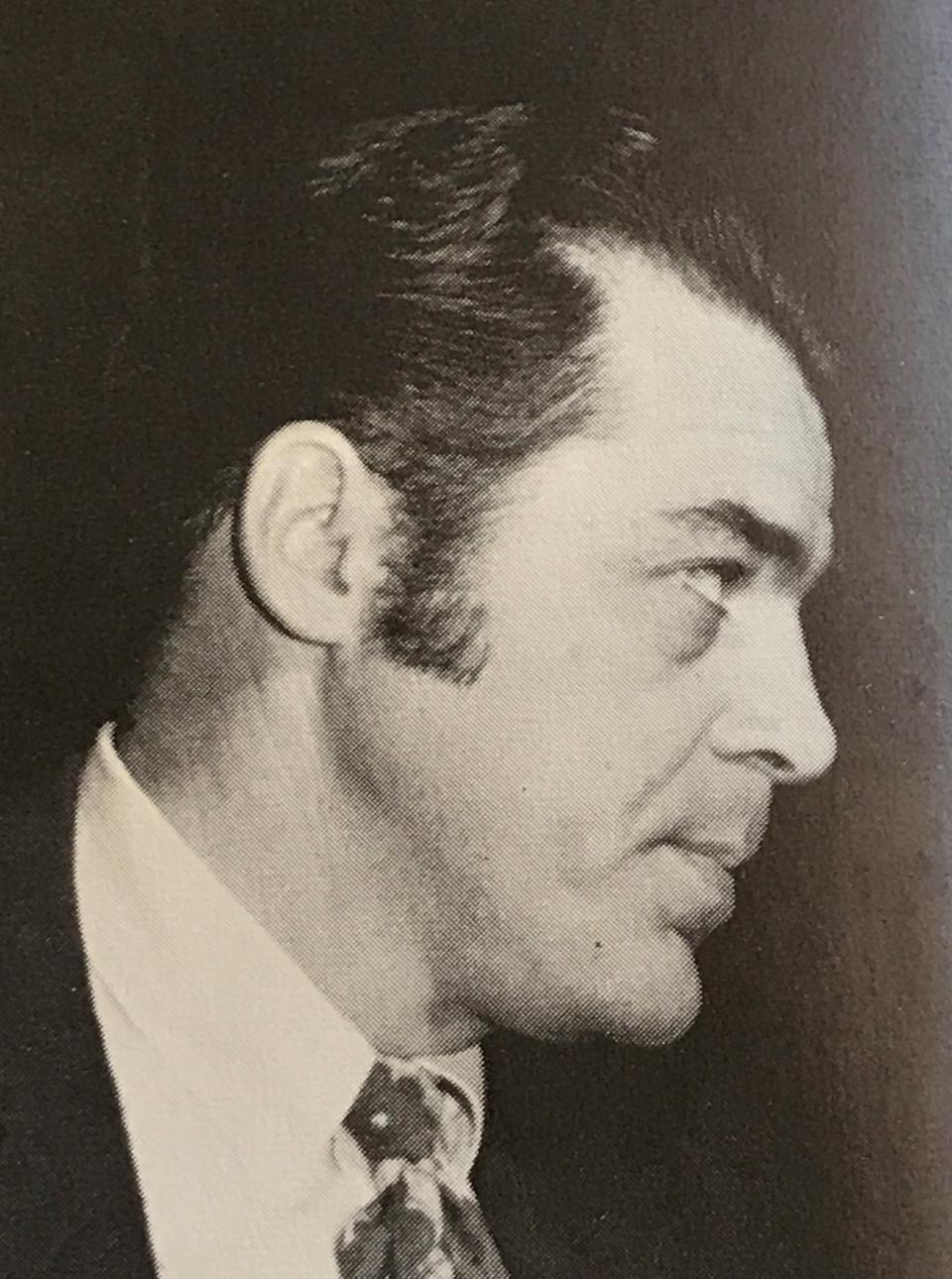

Edwin D. Fleming, now living in Fort Mill, South Carolina, is remembered today as the father of Renée Fleming, the renowned soprano.

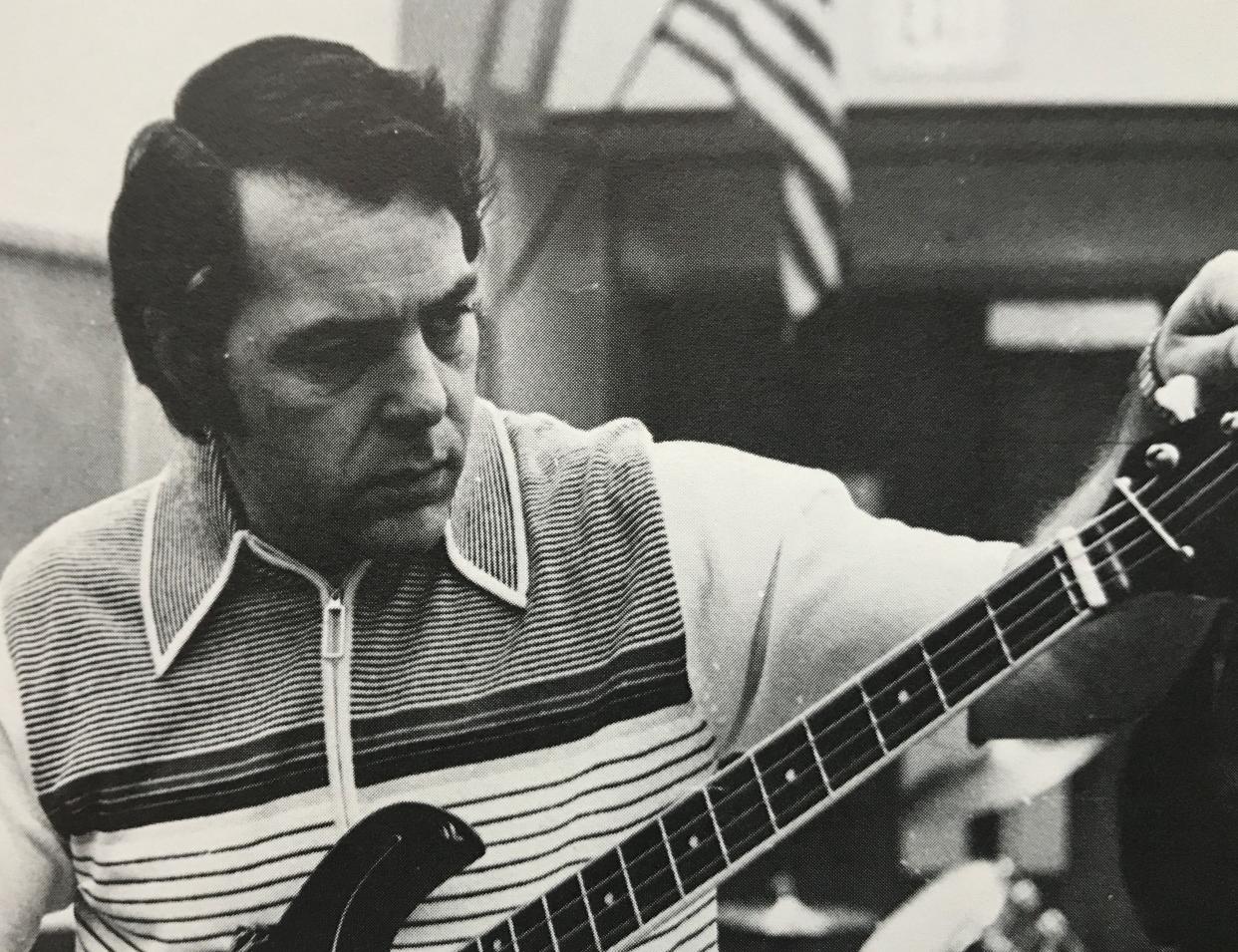

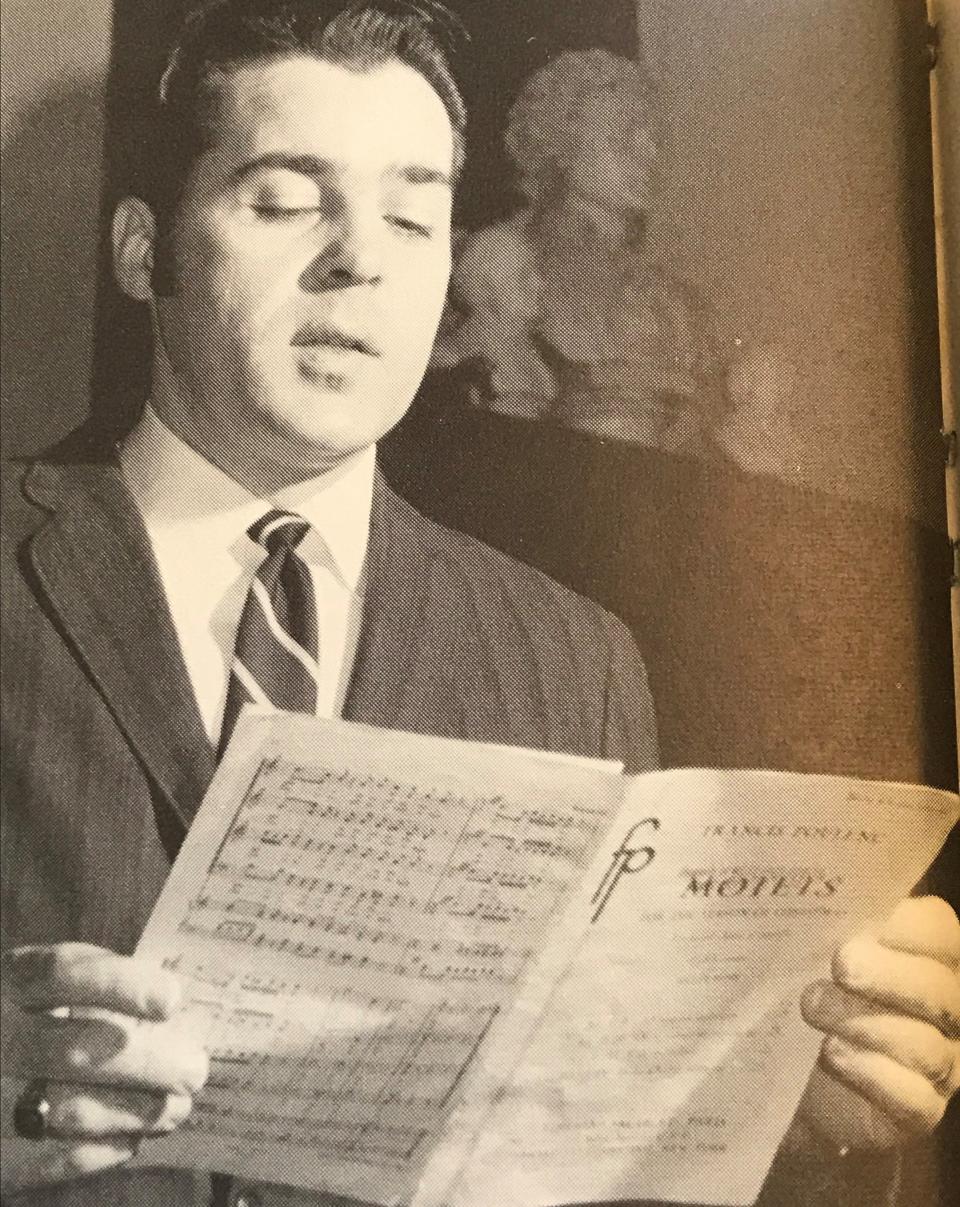

But in the 1960s and '70s, he was a highly-regarded vocal music teacher. He taught at West High School and moved in 1971 or 1972 to East High, which had the city’s best music program.

He became department head there. He also directed church choirs, an all-county school choir and sang with the Opera Theater of Rochester.

"He was good. I went there excited by the things that I had heard about the music program, the choruses, the music lessons," said Edward Cavalier, the now-retired principal at East High who joined the administration there in 1981. "He was well-thought-of."

Renée was at Churchville-Chili High School during the same period the two women were at East High.

Attempts to reach Renée Fleming for comment on this story were not successful.

In her 2005 autobiography, The Inner Voice, Renée Fleming described her father as "handsome, with a soft lower lip and shining black hair that fell across his forehead in an Elvis Presley curl."

Laura, whose encounters with Fleming took place in the early 1970s, recalled his "big, round face and baby soulful eyes.

"He was well-dressed and kind of had manners and he was debonair. I think he liked to think of himself as, you know, a European-style, sophisticated person in the arts," she said.

Betty, whose experiences with Fleming she said were violent, remembers him as only as a teacher, an authority figure. She said one of her friends "thought he was creepy."

'I was like a robot'

When Betty went to the East High music room to pick up her guitar that day in the spring of her freshman year, just after she’d turned 15, Fleming was the only other person there.

"He said ‘just a minute’ and he went over and he locked the door," Betty recalled. "He took my guitar from me and put it down and started, I guess you would call it, kissing and everything, and took me into this office and…"

She paused for a moment.

"And had sex with me. Forced me," she whispered. "And then when it was over, he slapped me."

Her abuse continued, Betty said, for more than two-and-a-half years. In her legal complaint, she puts the number of incidents at more than 40.

"At one point, he said to me that when I say I want you here, you need to come here after school," she said. "So in the middle of class, in front of everybody, he would say 'Betty, I need to see you after school, or I want to see you here after school.'"

Every time he summoned her, she returned to the music room. She said he was always prepared with a condom.

"Having the benefit of the last 45 years it's like, 'Well, why didn’t you just not go?'" she said. "Why didn’t this, why didn’t that and then, you know, those thoughts haunt you and you feel stupid and embarrassed and like a horrible person because you did this terrible thing and you allowed this thing to be done. But at the time, you're terrified.

"And I was terrified every day of my high school years. So when he said, 'I need to see you,' I was like a robot and I went. That was it."

She confided in a friend as the abuse continued, omitting some of the details and not mentioning the slapping and hitting, "but the interesting thing is that neither of us thought to tell anybody else," she said.

Betty said if Fleming felt she was starting to resist his commands, he would pile physical abuse on top of the sexual abuse.

"He'd slap me or punch me and his thing was, 'If anybody does find out about this, it will be my word against yours. You'll never graduate from high school, I’ll make sure that you never go to college, I’ll make sure you’ll be embarrassed, you’ll be a whore.' So when you’re 15…"

She trailed off.

"This is why I'm completely paranoid of anybody finding out."

She once feared a family member had discovered what was happening, and in a panic tried to take her own life. The abuse finally ended, Betty said, when in her senior year she gathered the courage and threatened to tell an authority figure what Fleming was doing.

It would be two more years before she spoke up.

What the school district did

Betty enrolled in college after she graduated from East High, but had a difficult time living with what she said had happened to her.

"I started having flashbacks. I started having horrible nightmares. I was having alcohol issues," she recalled.

After her sophomore year, Betty's friend convinced her they needed to tell city school officials what had happened. Together, they sought counsel from a woman they knew who had been active in school district affairs.

In the summer of 1981, Betty, her friend and the woman lodged a complaint with Josephine Kehoe.

Kehoe had been vice principal and then principal at East High during the time that Fleming allegedly abused Betty. She left high school in June 1981 to become the district’s supervising director of secondary education.

She had been one of the first women to be a city school principal and went on to become the first woman in Monroe County to serve as a superintendent.

They met in Kehoe’s new office at the district’s downtown office. According to her legal complaint, Betty told Kehoe that Fleming had forced her to have sexual intercourse.

In a recent interview with the Democrat and Chronicle, Kehoe told reporters she remembered the meeting clearly, but she didn't recall how explicit Betty had been about Fleming’s alleged abuse.

She did recall that his alleged misconduct had taken place in a music practice room in an isolated part of the building with little traffic. Kehoe, who supervised the music department, would make rounds there occasionally.

"He had her in one of the practice rooms and he told her to be quiet when I walked by," Kehoe recalled being told.

Betty remembers being told that Fleming had been the subject of rumors. "Dr. Kehoe said to me, 'I know there have been whispers, I know people have been talking, but you’re the only one who's come forward,'" Betty said.

In the recent interview, Kehoe denied having heard rumors about Fleming’s conduct.

Kehoe said that after the meeting ended, she confronted Fleming with the accusation.

"When I faced him with that, he resigned that same minute," she said. She didn’t recall what Fleming said or if he admitted to any misconduct.

No police report

Betty said Kehoe told her during their meeting what would – and would not – be done.

"She said, ‘We will ask him to resign, but we are not going to put it in his file why he's resigning because I don't want to ruin his career. He's a dear friend of mine,’" Betty said, quoting her recollection of Kehoe's words. "It's weird the things you remember. I can tell you those words, almost word for word."

Betty recalled that Kehoe also told her not to call the police.

"You go to these adults and you think they’re going to do the right thing, and they’re going to protect you and instead, she asked me to not go to the police," she said.

Several days later, Betty said, Kehoe summoned her back to district offices.

"We went back and she did say to us that he resigned immediately," she said. "She said he didn’t argue it, he admitted it and that was that. It was literally maybe a five-minute conversation."

Kehoe denied ever telling Betty that Fleming was a friend or that she wanted to spare his career and asserted that the police weren’t notified at Betty’s urging.

"I’m sorry. I feel terrible for her. I just recall her being satisfied that he would lose his job but she didn't want more because at the time she was seeing someone who she thought she might marry."

Betty said she's still angry with Kehoe.

"You feel like you’re a piece of trash because you go and tell an adult and that adult, not only do they not do anything, but they basically tell you don’t do anything," she said. "And honestly, I shouldn't have listened to that. But I was afraid. I didn’t want to go to court. I didn't want my dad to find out."

Today, policies and rules are in place at the Rochester school district that would prevent an outcome such as the one about which Betty complained, district spokesman Carlos Garcia said.

All allegations must be reported to central office immediately, and staff members who witness or hear of child sexual abuse must fill out a form that is sent to police, Garcia said.

Any teacher or other employee accused of child sexual abuse would be placed on leave and likely fired if the accusations were borne out.

He also said Fleming's file had been thrown away in accordance with state record-retention rules and there was no way to know if it had contained any reference to the abuse allegations.

Garcia said district officials had no comment on the Fleming litigation.

'Tappity-tap-tap'

When Laura learned in recent weeks what Fleming allegedly did to Betty, her thought was that she might have gotten off easy.

"It probably emboldened him to move on to bigger and worse things," Laura said of the abuse he allegedly inflicted on her.

When Laura entered East High in 1970, she was, as she puts it now, "just a virginal, shy, quiet girl."

But she liked to sing. She was in the school choir and in her junior year took a voice class with Fleming. She said the class was held in a large practice room with an attached office.

"He took a liking to me and started taking me into his private office and give me busy work to do," Laura said, recounting how he once had her type out the full lyrical script to the opera Porgy and Bess.

"I thought it was kind of an honor, like he picked me out of everybody else to put me in there."

One afternoon, as she was typing, Fleming strode into the office and began stroking her hair.

This became a ritual.

"He would help me stand up, kiss me, caress my entire body," Laura said. "I mean, really my entire body, my breasts, my behind, my crotch. He would kiss me. I’d never been kissed by a man and I would just kind of stand there stiffly."

As the weeks and months progressed, Fleming would tell her she was beautiful and whisper "I love you" in her ear, she said. He'd set his class full of students to some task or another and disappear into his office with her.

No other students ever asked what was going on behind that closed door, Laura said. And she never told.

She was able to resist his repeated invitations to join him in a small recreational vehicle that Fleming drove to work and parked in a side lot near the high school.

"I always had this gut feeling that something really bad would happen if I went out to that RV," Laura said.

But she didn’t know how to stop him from groping her in his private office.

"I was raised in a home where you just let the adults be the boss and I didn’t have any inclination to push him away or tell him to stop," Laura said.

"I felt that he had regard for me," she said of Fleming. "And I felt maybe I should be pleased that I’m getting this attention. I was really confused by it."

'I just felt snuffed'

Over time, she came to realize how wrong Fleming’s actions had been. She finally spoke about what happened after a few glasses of wine with friends at her 60th birthday party.

"I remember his office, that tappity-tap-tap of the typewriter I was typing on and not really much else. Not much of the classes or anything, it was just that room for me that I was encased in," Laura said. "It was a long time ago, but I really remember that office. In fact, I was recently in that high school and walked down to the music wing and it really creeped me out just being around there."

She finally had enough partway through her senior year.

Laura fled East High, moved out of town and changed her name so she could "start over, you know, as a new person who wouldn’t be a victim."

She did not finish college, she said, because she was fearful of male professors.

"When I was in the early years of high school, I always wanted to go to … one of the famous women's colleges and become a journalist or an attorney or some great job, some great future," she said. "But by the time I was done with high school, I just felt snuffed."

All these years later, Laura shares, she’s still excavating the debris Fleming’s alleged abuse left on her psyche.

"It’s very easy for me to think, ‘I’m fine,’" she said, voice breaking. "But the truth is, I’m not fine. I’ve been single almost my entire life. There’s no reason for that. I should have been in a happy marriage all these years...I just feel like it impacted my feelings about who I am and my value to this world.

Fleming went on to teach

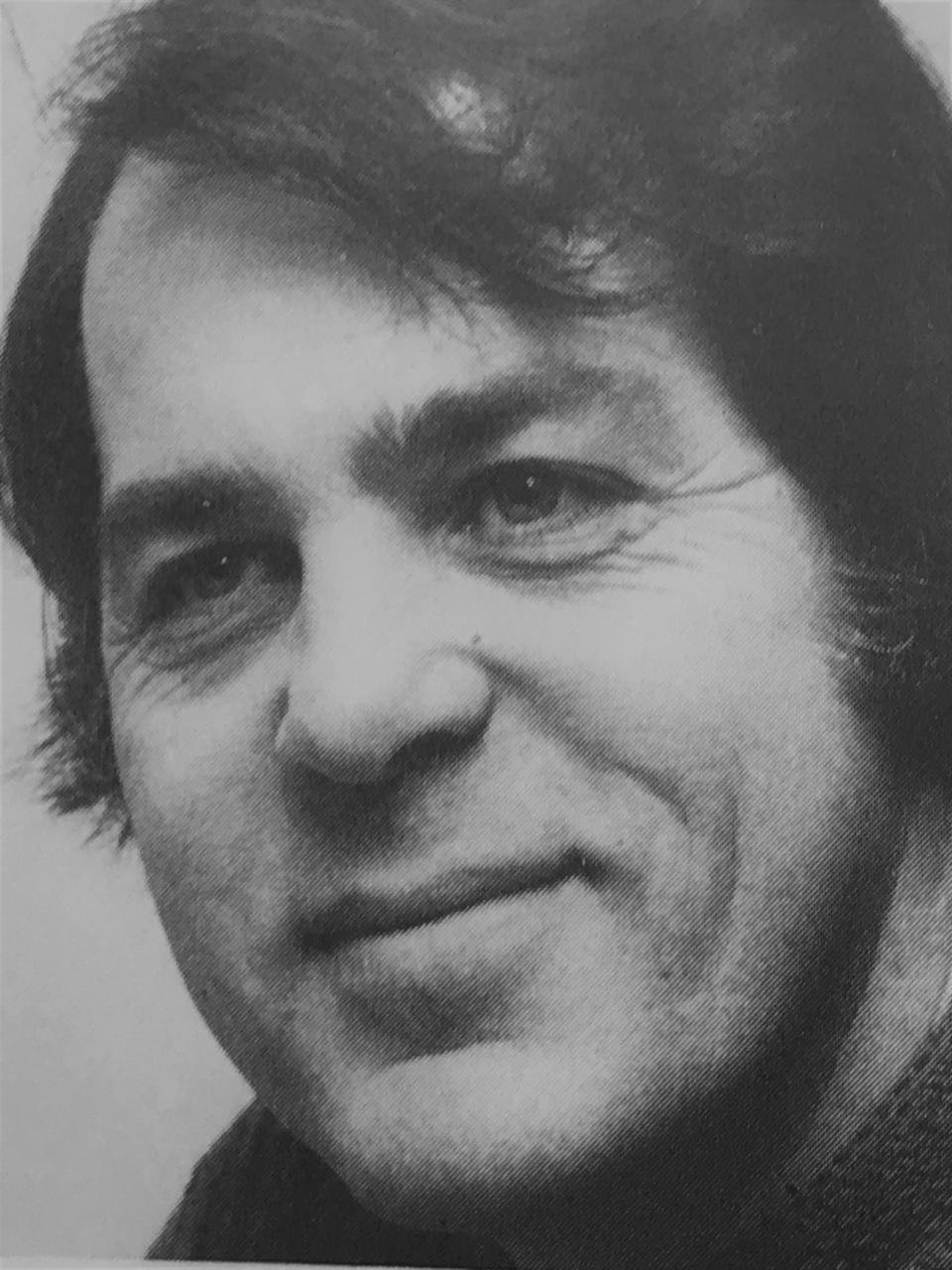

Adam Urbanski, the long-time leader of the Rochester teachers union, had a nodding acquaintance with Fleming when they both taught at East High in the 1970s.

And by happenstance, Urbanski learned of the accusations against Fleming shortly after Betty came forward in 1981 in a way that indicated that word of Fleming’s alleged misconduct, and the decision to allow him to resign, had reached the highest echelons of the district.

By then, the full-time Rochester Teachers Association president, Urbanski was meeting with then-city schools superintendent Laval Wilson when Wilson mentioned "as a courtesy" that allegations had been made against Fleming and "he would be resigning."

"I remember asking him one question when he said that to me. I said that I trust a condition of that would be that he get some treatment or therapy. But I do not remember the response or if there was any response at all," Urbanski said.

Wilson, who is retired after a long career in public school administration, could not be reached for comment.

Fleming left East High before the start of the 1981-82 school year and later worked for six local school districts, according to records released by the state teacher’s retirement system pursuant to a Democrat and Chronicle open-records request.

And on Nov. 12 and 13, 1987, Fleming worked somewhere in the Rochester City School District.

Garcia, the Rochester district spokesman, said the district today "would not knowingly employ anyone that it had reason to believe sexually assaulted a student."

Fleming didn’t teach again in New York after that school year and apparently moved out of state thereafter. He lived in Palm Beach County, Florida, for a time; school officials could find no record of him teaching there.

Edward Cavalier, who would spend 15 years as East High’s principal, was the vice principal that summer when Betty met with Kehoe to accuse Fleming. He said in a recent interview that he heard about the meeting shortly after it ended.

Cavalier verified that no police report was filed, and said he was told that Betty didn’t want one.

"It was not my call," Cavalier said. "In those days, you solved the problem any way you could. They didn’t necessarily take the action that would prevent it from happening again.

"It’s better now," he said.

Quiet resignations now rare

Rosen, from the child advocacy center, agrees that quiet resignations are less frequent than they once were.

"What we used to see was an institution saying 'Oh, we’ll handle this ourselves.' State law now prohibits that," she said.

Since 1973, while a major child-abuse reform was adopted, the list of professionals that must report child sexual and physical abuse has grown. Today, doctors, dentists, social workers, camp directors, day care center workers, police officers, therapists – and yes, teachers, school counselors and school administrators – are obligated to inform authorities if they suspect a minor is being harmed.

While most mandatory-reporters take that responsibility seriously, Rosen said, that doesn’t mean that every suspicion is phoned in to child protection agencies or police. People still have a tendency to disbelieve a young person who reports abuse.

And while the practice of letting a suspected perpetrator off easy is less common than it once was, it’s not extinct.

"It’s institutions that are enabling the behavior. I have always found it to be a particularly tragic element of these stories of child sexual abuse," Rosen said.

"The motivation is twofold. One aspect is quite human – the very natural question, 'What if I’m wrong? What if I expose this alleged behavior and it turns out not to be true and I’ve ruined someone’s life?'

"The other motivation is significantly less human and less understandable – and that is to avoid culpability and avoid financial liability," she said.

"You have a merging of human fallibilities with institutional self-interest to avoid financial and legal responsibility. That combination is very toxic."

Why now? #MeToo

As the #MeToo movement swept across the world and other women found the strength to speak up and fight back against sexual violence, Betty and Laura began to reexamine their own lives.

Through much of her life, Laura said, she tried to minimize what happened to her, telling herself that her abuse wasn’t significant because other people have suffered more.

"I just didn’t think it really measured up to other abuse I’ve heard about," she said.

She realizes now she was wrong.

"It truly did have an effect on me and I just didn't put it together until I was older," she said.

Seeing women expose the misdeeds of powerful men like Bill Cosby, Charlie Rose, Harvey Weinstein, and Louis C.K. had a profound effect on Betty.

"You know, you want to do something," said Betty. "And you feel like you’re enabled now. You have this strength behind you. You’ve got this army of female soldiers who came before you…like you’re being lifted up on the wave, which I never felt when I was younger."

When the Child Victims Act became law, both women decided it was time to raise their voices.

"What’s pushing me forward is the ones that came before me," Betty said. "Now I'm hoping that we might be the soldiers for somebody else and that we will be the army behind them."

Contributing: Kevin Ellis, managing editor of the Gaston (N.C.) Gazette, contributed to this story.

Here's the real Democratic debate: Which one can defeat Donald Trump?

Prince Andrew scandal: Accuser's lawyers praise his resignation; Queen Elizabeth stays busy

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Child Victims Act: Accused rapist Edwin Fleming kept teaching