'Young ladies do not swing their arms that way': Book reveals how UT women's athletics evolved

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Texas author Michael MacCambridge knows his pop culture cold.

The former music and film critic for the American-Statesman (1988-1995) writes with equal acuity about subjects such as media, literature and modern history.

Yet since 1997, when his first book, "The Franchise: A History of Sports Illustrated Magazine" came out, MacCambridge — disclosure: a good friend — has written volume after clear-thinking volume about sports as social, cultural and economic powerhouses.

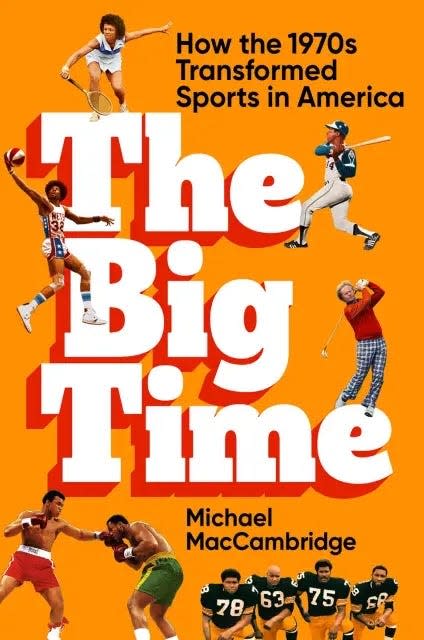

His most recent outing, "The Big Time: How the 1970s Transformed Sports in America" (Grand Central), which comes out Oct. 10, might be his most ambitious project to date.

And the state of Texas takes center stage almost from the first chapter.

"So much that we take for granted about sports today either began or reached critical mass in the 1970s," MacCambridge writes, "the move of sports into prime time on network television; the dawn of free agency and the beginning of athletes gaining a sense of autonomy for their own careers; integration becoming — at least within sports — more the rule than the exception; and the social revolution prompted by Title IX legislation that brought females into the world of sports in unprecedented numbers, as athletes, administrators, coaches and spectators."

More: New Title IX laws go into effect

On this last trend, MacCambridge writes tellingly about the seismic changes in women's sports in Texas, particularly at the University of Texas. There, the philosophy of ladylike exercise propagated by physical education teacher Anna Hiss from 1918 to 1957 — a UT gymnasium is named for her — abruptly became about competition and winning under women's athletic director Donna Lopiano during the 1970s.

I asked his permission to run an excerpt from the book about these powerful, fascinating women and their diametrically opposed attitudes about women in sports:

Hiss: 'Young ladies do not swing their arms that way'

If there was one university in America that encompassed all of the contradictions and challenges of the coexistence of men’s and women’s sports, it was the University of Texas in Austin.

It was often said that Darrell Royal could have been a governor or a senator if he’d wanted, because in the nearly two decades he’d been at Texas, he’d brought multiple national championships and created an athletic program as big and powerful as the aspirations of the school’s legion of boosters. That ethos of organized competitive excellence had been followed by coaches in other sports — notably Cliff Gustafson in baseball and Harvey Penick and George Hannon in golf — also earning national honors.

Women athletes at UT, on the other hand, were largely invisible, though this was a matter of choice. For decades, the female students who sought physical education or longed for extracurricular athletic activities at UT were all under the guidance and unblinking eyes of their protector, advocate and chaperone, Anna Hiss.

More: A Title IX lawsuit casualty, gymnastics program could have been a success for Texas

Raised in a moneyed but troubled family in Baltimore, the young Anna Hiss found refuge in scholarship and physical activity. She was 13 years old when her father, having been ruined financially, took his own life. Hiss set out on her own, far from her family, and forged her own way. She was 61 and already an institution at UT in January 1950 when her younger brother, Alger, made national headlines, leading to his later conviction on two counts of perjury for lying to a grand jury about spying for the Soviets.

As always, she lost herself in her work. Hiss had been a proponent of young women engaging in athletics as a way to promote comportment and posture rather than to attain peak athletic performance. She viewed competition — especially intercollegiate competition — as anathema to the development of young ladies.

So Hiss designed the women’s physical education program at UT to avoid the corrupting influences of the male gaze and the dreaded beast of competition. To that end, the court to play basketball was purposely built short of regulation length and surrounded by close walls so as to avoid spectators. The pool was similarly built short of competition length, so there could be no intercollegiate meets.

In her decades at UT, Hiss oversaw physical education programs for thousands of young women. One of them was the Texan Waneen Wyrick, who in 1953 was a freshman at UT. Her athletic dreams had already been dashed during her first days in Austin.

“I was active in the early ’50s and I was not allowed to do anything in athletics,” she recalled. “In fact I was told by a professor when I arrived as a freshman at the university that I could not be a teacher and a softball player. Because women softball players were cheap, and smoked, and drank beer, and teachers could not be seen as that kind of lady.”

Hiss had an office on the ground level of the Women’s Physical Education Building. She kept her door open, the better to supervise the young co‑eds. Wyrick had two encounters with Hiss that semester. The first, she was whistling while walking by, and Hiss called her into the office. “Young ladies do not whistle when they walk — or any other time, for that matter.”

Another time, Hiss summoned Wyrick into her office to inform her that, “You are swinging your arms too vigorously; young ladies do not swing their arms that way.” Wyrick didn’t stop swinging her arms, but she did stop walking by Hiss’ office, choosing instead to regularly detour through the basement to the stairs on the opposite side of the building.

After Hiss retired and the building was renamed in her honor, the Anna Hiss ethos was still embraced, to a great degree, by Betty Thompson, the head of UT recreation department. Thompson was also a supporter of athletics for its comportment and health benefits. Reserved and dignified, she played squash regularly, either at Gregory Gymnasium or on the ninth floor of Bellmont Hall. And she never, ever kept score.

The dozy, prim ethos that characterized women’s athletics at UT was all about to change.

Lopiano: 'I’m a Yankee, I hate country music'

With the prospect of Title IX implementation looming, Royal made it clear that he had no interest in overseeing the women’s athletic program at UT. Modest funding of $128,000 was approved for a separate women’s athletic department and director of women’s athletics. The head of the committee recommending a women’s athletic director would be the same Waneen Wyrick — by now Waneen Wyrick Spirduso — who as an undergraduate had been scolded by Anna Hiss two decades earlier, and was now back at UT, teaching in the kinesiology department.

Spirduso reached out to Carole Oglesby, the first president of the AIAW, for recommendations. One of the women that Oglesby named was an energetic, fiercely competitive woman named Donna Lopiano, only 28 at the time. They’d been on opposite sides for some epic Amateur Softball Association games, Lopiano pitching for the Raybestos Brakettes, Oglesby hitting for the Whittier Gold Sox.

More: Golden: Texas' national women's sports takeover couldn't have come at a better time

Lopiano’s life had already been a refutation of every cliché about women being uninterested in sport. She was an athletic prodigy, dominating the sandlots and the newly opened Mickey Lione Park off of Stillwater Avenue in Stamford, Connecticut. She grew up loving the Yankees — Mickey Mantle of course, but also the pitchers Don Larsen and Whitey Ford. She modeled her wind‑up on Larsen’s.

Her childhood was marked by the spring day in 1957 when the 10-year-old Lopiano and her friends ventured down to Lione Park to try out for the Little League baseball team. Lopiano’s prowess was well known in the neighborhood, and she was among the first players chosen. Later, waiting in line with her new teammates to pick up the team uniforms of shirt and cap, she saw that she’d been assigned to a team with the same midnight blue color as the Yankees — dark cap, pinstripe shirt. She thought happily it was an omen.

Just then, a man came up to her — the parent of another player — holding in his hands a Little League rulebook, and showed her the provision that prohibited girls from participating. Tears welling up in her eyes, Lopiano went out of the line and left her friends.

That summer, she just kept crying. Watching games, reading at home, the tears would come without warning. Her parents tried to find her some league — any organized league — in which she could participate. But there was nothing in Connecticut in the mid-’50s for young girls.

More: Women's pioneer Lopiano still trying to level college sports' playing fields

Her parents ran Casa Maria, an Italian restaurant named after her grandmother, in Stamford, Connecticut. One evening in 1962, Lopiano’s father plied his friend Sal Caginello — a high school baseball coach and regional scout for the Pirates — with Chianti, and persuaded him to get Lopiano a tryout with the powerful traveling softball team, the Raybestos Brakettes.

Caginello was hung over and regretful the next day, but he kept his word. On the day of the tryout, Caginello picked up Donna, but didn’t say a word to her on the 25 mile drive up to Stratford, where he introduced the young girl to Wee Debbits, the manager of the Brakettes, then returned to his car.

Lopiano proceeded to hit everything, and showed good fielding sense and great promise as a pitcher. It would take her a year to adapt to the underhand delivery. But she instantly earned a spot on the Brakettes.

She’d spend much of the next decade playing softball for the nationally ranked Brakettes team, part of an awesome pitching duo with all- time multisport great Joan Joyce. Lopiano would go to Southern Connecticut State University and major in physical education, then got her master’s and, later, her Ph.D. from USC. After finishing her coursework, she applied to 50 schools before getting hired — still in her mid-20s — as the assistant athletic director and women’s softball, basketball and volleyball coach at Brooklyn College.

Dark-haired and decisive, there was a headstrong brusqueness to Lopiano, the aura of a woman in a hurry to right past wrongs, and fiercely advocating for her right to a spot at the table and on the field. In her athletic career, she had competed for 23 different national championships in four different sports. She didn’t need to be told about the value of competition.

She flew to Austin to interview for the women’s athletic director job, and was introduced to Darrell Royal at a lunch in the Headliners Club in downtown Austin.

Royal lobbed the prospect an easy pitch: “Donna, do you like country and western music?”

Lopiano, for all her idiosyncrasies, remained an Italian from the East Coast, and one completely unaware that Royal was a regular golfing partner of Willie Nelson.

“No,” she explained. “I’m a Yankee, I hate country music.”

Several people in the lunch party looked down at their plates during the pregnant silence that followed, which was broken soon by Royal’s gentle laughter. He took it in stride.

The hiring process soon reached a stalemate. The new president at the University of Texas, Lorene Rogers — a biochemist who’d just become the first female president of a major research university — had asked Spirduso’s committee for three candidates, but while the committee had sent her a list of three names, it only recommended one candidate: Lopiano.

Rogers demurred. She had gotten wind of Lopiano’s visit and summoned Spirduso to her office to discuss it.

“I don’t want to hire Donna Lopiano,” Rogers said. “She’s harsh and grating, and she’ll alienate Darrell. He doesn’t like her.”

“She’s smart and she gets things done,” responded Spirduso. “She will learn — and learn quickly — how to navigate.”

Rogers grumbled that she would think about it. A few days later, she wrote Spirduso to say she could hire Lopiano. As it turned out, both women were right. Donna Lopiano would alienate Darrell Royal, but she’d also learn how to adapt.

In the process, the noncompetitive philosophy of the Anna Hiss Gymnasium would be wiped out by Lopiano’s thirst not merely to compete but to excel on every athletic stage possible.

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Waneen Wyrick, Donna Lopiano built Texas women's athletics program