Young robotics engineers work to give 'Red Bull' — and themselves — championship wings

From the outside, the space is unassuming, another storefront in a light industrial park in Chandler. Architecturally, it gives little away: red brick, concrete, tinted windows, gravel. Its perimeter is lined with empty parking spaces. And the only clue to what’s inside requires some basic Spanish.

“Si Se Puede Foundation,” reads the lone sign tacked to the wall outside. There's a logo of two birds carrying a leafy twig.

Inside, in what is clearly a workshop, the mood is electric. A corridor doubles as a busy thoroughfare, teeming with young people, high schoolers most of them, wearing bright red T-shirts. They duck in and out of a conference room, tap away in a computer lab and chat by a silent shelf of 3D printers waiting for their next task.

In a classroom, whiteboards covered in text and diagrams run the length of one wall, the backdrop to a fervent planning discussion. Here, the number of students on missions increases, and so too does a loud buzzing sound, emanating from a white door in the corner.

The door opens to a cavernous workroom, replete with banners and a dizzying array of mounted tools. Screeching saws are being operated by teenagers wearing safety glasses and big white ribbon bows that, one student explains, signify an “enduring commitment to empowering female engineers.” Across the room, others are wrestling yellow pool noodles into tubes made of bright red canvas.

Amid the chaos — which, it must be said, is occurring within the parameters of standard workshop safety regulations — a little whirring robot struts its stuff. It travels across a practice area in spurts and fits, alternating between launching balls into an 8-foot-tall plastic funnel and swinging precariously on a set of uneven bars.

Its name is Red Bull.

In February, one of its creators, Liz Seaton, witnessed a moment of perfect synergy. She and the team had gathered for the robot’s first-ever test drive. The mechanical team had built the robot. The electrical team had wired it. Liz’s team had programmed it. And it worked.

“I remember the excitement flowing through me,” Liz says. “It was so awesome.”

Liz was first introduced to the field around age 10. “I think I programmed a picture of a koala,” she says. But it was not until last year, when she joined Degrees of Freedom (DoF), a Chandler-based robotics team run by the nonprofit Si Se Puede Foundation, that her passion — and possibly her career — began in earnest.

Now a 14-year-old high school freshman, Liz is in her element at the Si Se Puede STEM Center (STEM stands for science, technology, engineering and mathematics). No matter how much time she spends here — and lately, it’s been a lot — she always wants to come back. It’s not like she doesn’t have other stuff going on. She has schoolwork, and basketball, friends and a 10-year-old sister (who, obviously, now wants to join the robotics team).

But this spring, Liz is navigating the biggest programming challenge of her life.

Her mission is to get Red Bull — a beloved construction of metal, plastic and wire that sports little white wings and weighs roughly 105 pounds — to climb up the bars, each higher than the last.

Autonomously. As in, by itself.

It is a mammoth programming task for a freshman. But if Liz can pull it off in time for the FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) Championship in Houston this week it will give her team an edge. And Liz loves her team.

Seven days out from Houston, she is in the classroom, punching code into a laptop.

“It’s crunch time,” she tells The Arizona Republic. “We’ve got a lot still to do. But I think it's totally possible we can get it done, especially if we work hard.”

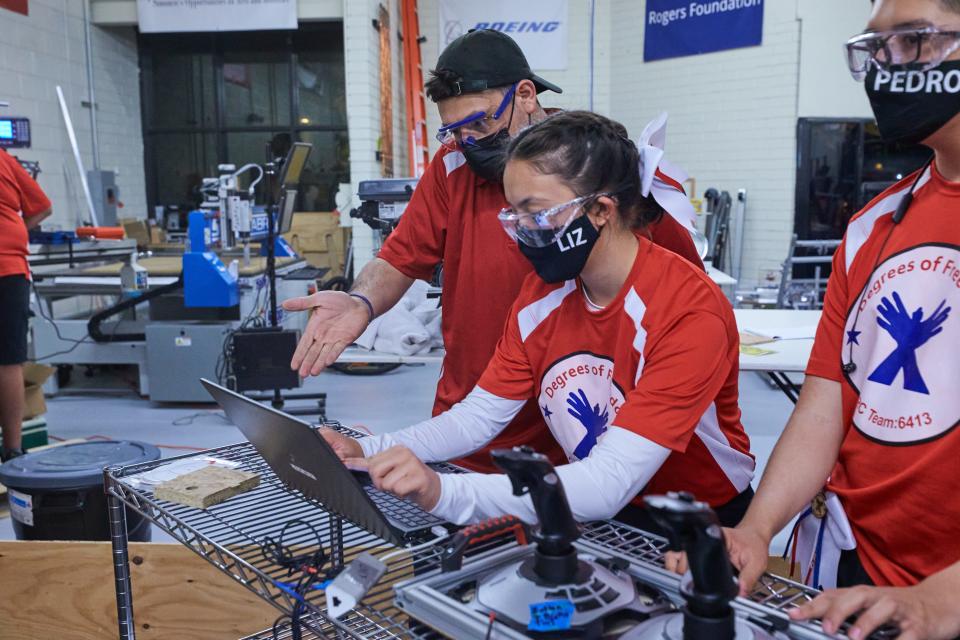

Next to her, mentor Juan Palomino offers a stream of advice in the form of questions that Liz registers, answer, and works into the code without her eyes ever leaving the screen.

Her red shirt displays the team logo, a blue silhouette of two open hands with thumbs interlocked to resemble a bird in flight. Her neat braid is affixed with the symbolic white bow. Her black mask has the DoF logo and team number, 6413, on one side, and LIZ in block white letters on the other. Her fingernails are painted in sparkly red and blue, one color on each hand — an idea she picked up from team captain Natali Rodriguez, who matched her nails and eyeshadow at the team’s last meet. On her feet are black Doc Martens.

“I'm proud to be here, you know?” Liz says. “Some of my friends will be like, ‘She's such a nerd.’ I'm like, ‘And? I'm building robots. What are you doing?’”

March 19: The road to Houston

The DoF teenagers are sitting in a high school gym in Scottsdale, a red patch in a sea of students, closely watching the awards ceremony for the FIRST Robotics Arizona Valley Regionals.

They had placed seventh. It was a strong result, but their robot was eliminated too early to secure a ticket to Houston. The students deeply wanted to make it to the championship, which everyone calls "Worlds," the highest level of FIRST competition between teams from across the globe.

Now they had one chance left: winning the Regional Chairman’s Award.

Known as just “Chairman’s," the award is described by FIRST as its most prestigious. It is about more than robots, though an impressive one is still required, and at its heart rewards a team that uses STEM as a force for good in the community. The winner would be announced last of all.

The moment was particularly fraught for Tanisha Baliga, Khushi Parikh and Maria Estrada, who had crafted the application making the case for why DoF should win. Prior to the ceremony, the girls had received conflicting information. Their coach, Faridodin “Fredi” Lajvardi, an old hand in robotics competitions, was a judge in other categories and knew who had won Chairman's. He had given a pep talk the teens interpreted as kind of dispiriting. On the other hand, Khushi had asked the Magic 8 Ball app on her phone if they would win.

Its reply: “It is certain.”

They had decided to enter just a week and a half out from the competition, mostly due to Tanisha's persistence. Mentor Izzy Thalman thought they had left it too late.

“I was like, I don’t know how to break it to (Tanisha) that I don’t think we can do this,” she says. But the 16-year-old Hamilton High student was very persuasive. “Of course, Tanisha doesn’t let me say no.”

The team had won once before, in 2019, and the three girls thought they had another shot. In the application essay, they drew on the DoF logo for inspiration, describing the team as “birds of a feather” with Si Se Puede, and as a group that had transformed over time into a “larger flock that strives to soar even higher”.

The team had changed a lot in the past year. Until 2021, DoF was an all-girls team, but when COVID-19 led to a dearth of money, mentors and budding engineers, they merged with their brother team, Binary Bots.

The transition came with some bumps. Lajvardi, who is the vice president of STEM initiatives at Si Se Puede as well as a hybrid coach/manager for DoF, recalls some initial resistance. But it ebbed, he said, after the students realized more people meant more time to specialize in the parts of robotics they were most interested in. Mentor Megan Cheng noticed that while the girls tended to wait their turn to speak, the guys would jump in, eager to say their part. After some changes, like raising hands and calling on people instead, the group adjusted.

Still, DoF retained a feminist core and ethos. It is reflected in the team’s structure, with all leadership positions occupied by girls or nonbinary people, all of them people of color. It is symbolically manifested by the white bows, which students of all genders wear proudly. And it is evident in the experiences of students, who talk passionately about what it means to be part of a place that welcomes and celebrates them just as they are.

It means a lot to Maria to be a Mexican woman in STEM.

“It really brings me joy that I get to inspire my family members and other people in the community,” she said.

Khushi said she overcame her self-doubt about venturing into the field after watching women succeed on the Arizona State University and Si Se Puede college team, Desert Wave.

Tanisha was drawn to the fact that in DoF she could do hands-on work, instead of people assuming she would take on a secretarial role.

“I could ask questions without feeling like an idiot because every man wasn't trying to sit there and explain basic concepts to me,” she said. “Like, I know how to use a saw. I’m asking how the code works.”

Eight languages are spoken among DoF’s 17 students, who hail from a variety of high schools. Many of them speak Spanish, which has allowed them to promote robotics to parents from the local area in their first language, and to mentor a rookie team from Mexico. They have guided youth teams, and adapted toys for children with disabilities.

Recently, the team Zoomed with a STEM organization based in Ghana, and now has plans to fundraise for robotics equipment for its 500 students and get one of their teams to next year’s championship.

The students have at times been surprised by their own strengths. For Khushi, one past challenge sticks out. The task was to create an assistive technology necklace for a girl who was losing her sight and speech. The jewelry would consist of interactive beads, with a braille letter on one side and an icon on the other, allowing the girl to communicate.

Creating the beads required software Khushi didn’t know how to use. “I remember going into that project thinking I wouldn't be able to contribute anything,” she said.

What she could offer was just as important as the software: empathy, for a fellow teenage girl. “What do we need to tell our teachers? What do we need to talk to our parents about? What are some emotions and needs that we have? How can we make this necklace into something that's a stylish piece that she'd want to wear?” Khushi said. “Little things like that, that key to understanding her, is why giving a voice to these underrepresented communities in STEM is so important. Because you come out with products that are more inclusive and more user oriented.”

When Cheng, now a software engineer at General Motors, was growing up, conversations about diversity never got further than, “Oh, you’re a girl. That’s so great.” Cheng, 26, said it was amazing to see the students fully recognize the unique contributions they can make to STEM.

“When people talk about diversity and engineering, it's not just like, ‘Oh, you think differently,’ but like, they really do bring different life experiences that some students may not have,” she said. “And through these different experiences, our team finds ways to help others who may not be seen, or who may be left behind as the world moves faster and faster.”

Tanisha, Khushi and Maria had done their best to relay all of this, or some version of it, anyway, to the judges. The verdict seconds away, Tanisha clutches the hands of Thalman and another mentor, her body twisted awkwardly to reach them both. Her eyes are tense above her signature black mask. She is sure another team, one with rockets in its branding, is going to win. As the ceremony announcer starts reading the judges’ comments, Tanisha scrutinizes every word for clues.

“One team takes to the sky, spreading the FIRST mission…”

I’m thinking of like, rockets soaring.

“… from using their engineering and robotics knowledge to mentor teams and engage with children …”

There's a program for younger kids, so that could apply to anyone.

“… to their analytical approach towards measuring their impact …”

What is analytical about our team?

“… the community flocks to this team.”

Flocks … Flocks!

Tanisha’s eyes widen. One of her hands flies up to cover her masked mouth. She gasps in delight. The team is buzzing now, slapping legs, turning in their seats, huge smiles radiating from under their masks. The announcer finally reaches her conclusion — “Team 6413!” — and the teenagers erupt in a sea of celebrating red.

Khushi’s Magic 8 Ball app was right.

April 6, 2022: Two weeks out

Natali Rodriguez, team captain and Liz's nail polish inspiration, is surveying the practice field at the Chandler workshop, where students are tending to a stationary Red Bull.

“I probably spend more time here than I do anywhere else,” she says. “This is probably like my second home.”

Natali, a senior at Chandler High, is in her fourth and final year as a DoF student. She became captain after a “nerve-wracking process,” she says, that involved writing out why people should vote for her, posting it in a team Slack channel. When she found out she had won, she was at Ikea, of all places, with Maria Estrada. “I was screaming and all happy,” she says.

She is interrupted by a loud whirring sound. Red Bull is back in action. The robot has scooped up two customized tennis balls, each red and roughly the size of a basketball. It drives forward and abruptly fires them in the direction of the giant funnel. One of the balls goes in, a neat basket. The other hits a fluorescent light hanging from the ceiling with a loud bang and ricochets off at an angle, leaving the long bulb swinging erratically.

Was that … a success? “I guess, to us, it will always need refining,” Rodriguez says. “It hit the light. But having one of the balls at least get in is a success to us, because it's kind of difficult, even though it may not seem like it.”

For Lajvardi, the coach, success is about more than winning and losing. He is a relentlessly animated man who explains concepts with gusto, often by reenacting conversations, and comes across as part engineering coach and part motivational speaker.

But he is best known for a robotics victory almost two decades ago. In 2004, while working as a teacher at Carl Hayden High School in west Phoenix, Lajvardi co-coached a team of four Latino students, three of them undocumented, to victory in a college robotics competition.

Team's legacy: In 2004, they beat MIT. Today, it's complicated

Their underwater robot, which was named “Stinky” and involved the artful deployment of tampons to defeat a last-minute leak, beat out schools including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Cambridge. A movie about the unlikely victory, starring George Lopez as a character loosely based on Lajvardi, was released in 2015.

Lajvardi happily recounts the enduring lessons from this astonishing triumph. One, you don’t get to choose who plays you in a movie (he wanted Keanu Reeves). Two, the boys won after he convinced them of a simple fact: Their brains were equal to the brains of the students from the fancy colleges.

“Genetically, there is no difference, right?” Lajvardi said. “If you believe that, then there's absolutely no reason why you can't compete.”

After 30 years in public education, Lajvardi joined Si Se Puede and was appalled by a study showing girls dropped out of STEM, or avoided it altogether, because of male-dominated culture. Now, he is working to instill a sense of self-belief in the DoF kids.

“You are the only one that can control whether or not you're successful,” he said. “If you let society decide that for you, you're doomed.”

Lesson number three: It’s all about human connection. Role models are essential, not just having them in the first place, but becoming them, too. Lajvardi recalls meeting a Latina woman at a convention who had driven her sons for 4½ hours to meet the Carl Hayden High School boys.

“I was stunned,” he said. “I realized in that moment, how much it means.” After the woman left, he leaned over to one of the boys, Lorenzo Santillan, and told him: “You’re a role model.”

“He goes, ‘I don't want to be a role model,’” Lajvardi said. “I go, ‘Too bad. So am I.’” If I don't always do the right thing, he told Lorenzo, people will think "Oh, you don't think you have to do that, because you're Mr. Lajvardi who beat MIT."

“‘So now I have to ask myself, what would the person who I'm supposed to be do?’” he told Lorenzo. “‘So now I have to do the right thing. Whether I want to or not. Because if I don't? Everybody's gonna know. There's no anonymity anymore.’ And he goes, 'But that's not fair.’ I said, 'Well, you can choose to live up to it, or let everybody down. That's the only two options I can see. So pick!’”

What does success look like for DoF? “For this team, if they're all positive and they come back on fire. That's what I want,” Lajvardi said. He wants the students to get ideas, get excited, and be even better next year. “Winning is not the only thing,” he says, “but knowing how to win is important.”

And the teenagers are working on it. The game they will be playing in Houston, Rapid React, lasts an intense 2½ minutes. For the first 15 seconds, Red Bull is on its own. If all goes well, Madhumitha “Madhu” Thumati, a 17-year-old junior and DoF’s programming lead, will get the robot, already pre-loaded with a ball, to autonomously pick up another ball from a defined spot on the field and fire them both into the goal.

Then Pedro Rojo will take over. The 18-year-old is the team’s lead driver, and in his final months of high school robotics before he heads to ASU's Walter Cronkite School of Journalism in the fall. He thinks he might want to work in audio. But first, he will commandeer the joysticks in Houston for 1 minute and 45 seconds of each game, maneuvering Red Bull from ball to ball, scoring goals and evading his opponents' defensive strategies.

In the final 30 seconds, Red Bull will attempt to climb up four bars. The low rung garners four points, the medium six, the high bar 10, and the uppermost, known as the traversal, a solid 15. Pedro can drive the robot up the rungs, with impressive ease, if he has to. But the aim is for it to happen autonomously.

That’s Liz’s task. Will the programming be ready in time?

“Definitely,” she says. “We have to have it ready for Worlds.”

Park University: Gilbert's move into higher education had a rocky start. This university has turned it around

April 13: One week out

With seven days to go, excitement is still the dominant emotion at Si Se Puede STEM Center. But stress is encroaching fast. In the workshop, Palomino, Liz and Madhu are in a brief programming team huddle.

“What is left after today?” Palomino asks the two girls, reminding them they need a definitive plan. “Tomorrow’s Thursday,” Madhu says in response, her face stricken, fingers on her temples. Then she and Liz begin to recite a list of tasks.

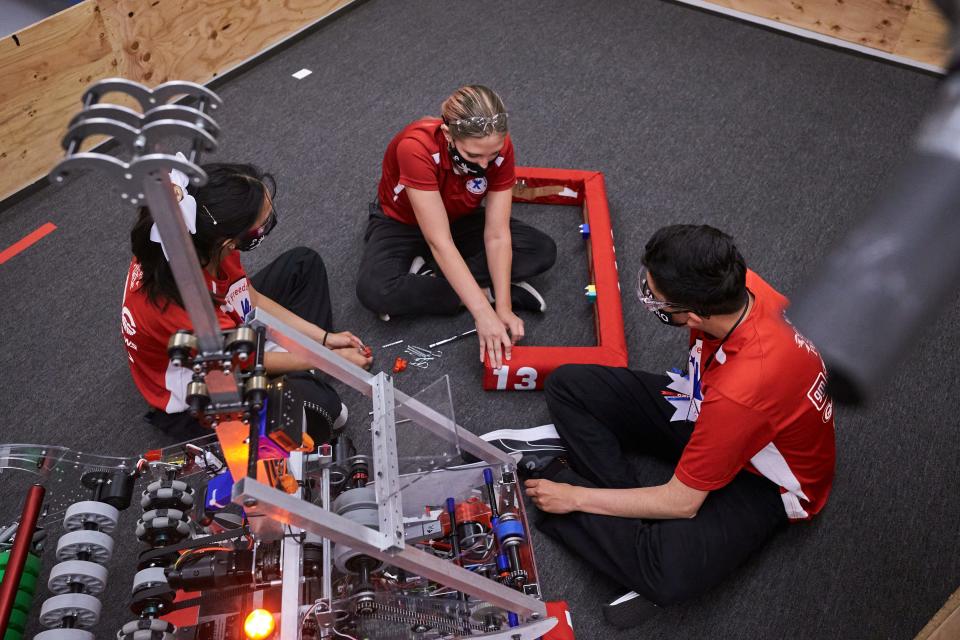

Behind them, eight people are crowded around Red Bull. (What’s with the name, by the way? Pedro: “Because Red Bull gives you wings!”) The robot is looking good. The pool noodles, ensconced in canvas, have taken their rightful place as safety bumpers. A little red sign bearing the team's sponsors is now attached to Red Bull's front.

In the conference room, Tanisha, Khushi and Maria are standing in a row behind a colorful stuffed bird, practicing their presentation for Worlds. Their speech draws analogies between the life of birds — like nurturing their young — and the activities of DoF — like mentoring youth robotics teams.

The three girls deliver their lines, one after the other, to the near-empty room. They finish with a flourish, their hands rising in unison in the position of the DoF bird logo. The routine is nearly perfect. A forgotten word here. Lines spoken too fast there. But the girls have high standards for themselves.

“A little rusty,” one of them declares. They immediately launch into a discussion of pre-presentation anxiety, and how it’s immediately followed by post-presentation anxiety.

Back at the practice area, the programming huddle is over, and students are constructing … something … out of white plastic pipes.

“This is a makeshift pit,” Lajvardi explains, a structure to serve as their home base in Houston. The team has a metal one, which lives in the workshop, but not enough funding to take it to Houston.

In front of the construction effort, Liz and Pedro are stationed at the metal trolley that holds the joysticks and the programming laptop. It’s a big moment. Programming preparations for the autonomous climb are complete. It’s time to start writing the routine.

Red Bull climbs by alternating between its two arms. There is an extendable metal arm protruding straight out of the top of the robot at a 90 degree angle, and a wide plastic arm that spans across Red Bull’s base. To climb, the metal arm first latches on to a rung and pulls the robot up. When it is high enough, the plastic arm reaches up and takes over the hold, allowing the robot to tilt. Then the extendable metal arm can reach for the next rung, and so on to the top. In theory.

Liz is writing the routine bit by bit, sending Red Bull up the rungs and incorporating things like the degree of the tilt into her code. At the start of every attempt, she calls out “Three, two, one!” Sometimes the robot does what she wants it to, and sometimes it doesn’t. But before too long, she presses a button and Red Bull makes it to the high bar all by itself.

Palomino erupts. “Yeah! Let’s go! That’s how you DO it!” He high-fives Liz. “Now let’s do it three more times. Make sure it wasn’t a fluke.”

It’s an invigorating early success. But getting to the traversal, the highest bar, is proving more difficult. Palomino and another mentor are stationed on either side of Red Bull, tossing foam underneath the machine as soon as it first latches on to soften any potential falls. They are also ready to step in and catch the robot if it doesn’t latch on properly, to avoid a catastrophic breakage.

As the night goes on, they seem to be rescuing Red Bull more and more. The two ends of the plastic arm won’t quite latch on symmetrically, leaving the robot hanging at an angle. They change the battery.

“Can I get a quick time check?” Palomino says. It’s 8:29 p.m.

“Ohhh,” Liz says. “My mom’s picking me up. I’ll just tell her I’ll be out a little bit later."

They keep going. “Three, two one!” “Three, two one!” “Three, two one!” The metal arm grazes the traversal once, twice. But it just won’t latch on. Suddenly it is 8:56 p.m. “This is your last one,” Palomino tells Liz. “Otherwise your mom’s not going to let you come back.”

“Three, two, one!” The arm moves, and hits against the high bar, a rung they have just about perfected at this point … but on the wrong side of it. “What?” Liz says. A few minutes later, at 9 p.m. on the dot, Palomino calls it. An autonomous climb to the very top is not happening. Today.

“You made incredible progress tonight,” Palomino tells Liz.

“I know, I know!” she replies, dancing with pent-up energy behind the metal trolley. But she isn’t disappointed. In fact, Liz is pumped.

“Tomorrow I’m going to get it. I’ve got that to look forward to,” she says. “I’ve got two tests tomorrow, and after that? Right here.”

She stabs a finger towards Red Bull. “Coming for this.”

Epilogue: The competition

The Degrees of Freedom team arrived in Houston on the afternoon of Wednesday, April 20, ready for practice matches.

Over the next two days, the crew competed 10 times, eventually placing 67th out of 76 teams in their division. They did not make it to the finals, but learned a lot and left excited for next year.

During the competition, Red Bull successfully climbed to the traversal bar twice.

Reach the reporter at lane.sainty@arizonarepublic.com. Follow her on Twitter @lanesainty.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona's Degrees of Freedom robotics team eyes world championships