'This is how you're going to change the world': Using Holocaust education to end bullying

A small group of Sharp Middle School students was quiet during a recent visit to the Nancy & David Wolf Holocaust & Humanity Center. When tour guide Julie Gore asked how many of the students knew a Jewish person, none of the kids raised their hand.

Phillip Sharp Middle School is a rural school in Pendleton County, Kentucky. It serves about 550 children, 95% of whom are white, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

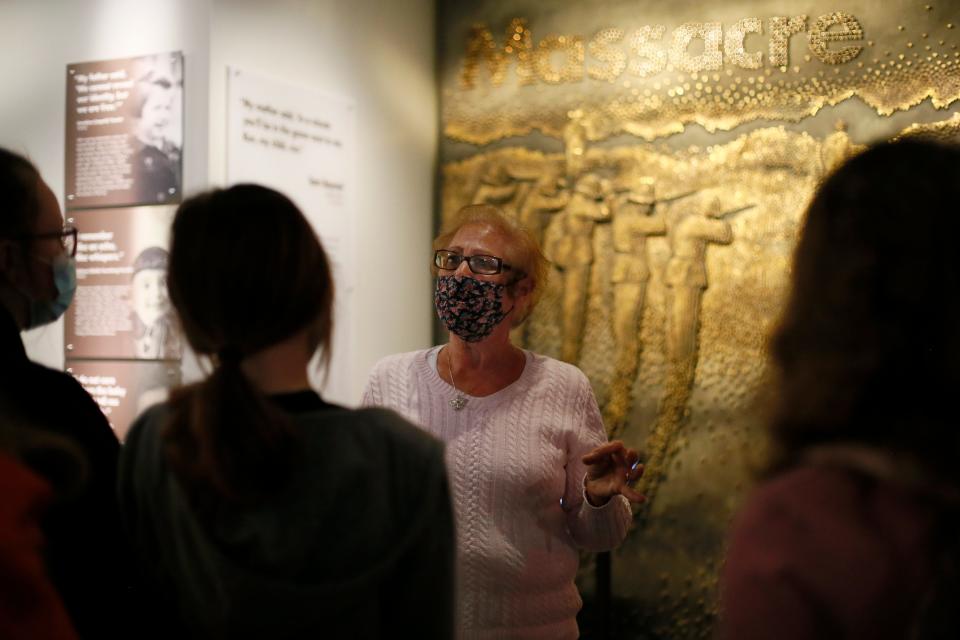

Gore led the students through the center, pausing to share personal anecdotes and expand on the local stories that line the walls of the museum. She asked them if they knew how to define key terms: antisemitism, upstander, bystander, perpetrator. She drew connections to current events like what's happening in Ukraine with people hiding, living in bunkers and fleeing their country.

Caroline Mains, an eighth-grader at Sharp, said she found the whole experience "inspiring."

It's important to learn about the Holocaust, she said, "so history doesn't repeat itself."

Lessons from the Holocaust: Standing up for others

Cincinnati's Holocaust & Humanity Center opened in January 2019 inside the Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal. The center asks visitors to reflect on their strengths, passions and ability to stand up for others in need.

Its mission and partnerships also make the case that Holocaust education is part of the solution to bullying in schools today, and helps promote inspirational leadership in our communities.

The center's desire to regularly host school field trips was altered during the coronavirus pandemic. Tours turned into virtual visits, which CEO Sarah Weiss said is effective but not ideal.

"There's something to being in a space," she said.

That's especially true at Union Terminal, she said, where many Holocaust survivors and World War II soldiers came through after the war. Gore started her tour in the terminal's center, explaining to the Sharp students the significance of the building to the local eyewitnesses students were about to "visit" inside the museum.

Holocaust education links history, social justice, anti-bullying efforts

Weiss said the museum connected with about 10,000 students before COVID-19 forced its doors to close. That number has more than doubled since the center reopened to visitors in July.

In the last nine months the center has engaged with nearly 25,000 students, she said, through tours, speaker series, traveling exhibits and Echoing Voices, an activity where students analyze the story of a local eyewitness to the Holocaust.

A new partnership will allow all Cincinnati Public Schools freshmen and a handful of other local schools, including Sharp Middle School, to send students each year for the next five years. The initiative is funded by Roger and Julie Heldman.

“We know that through this experience, students are learning about the dangers of prejudice, discrimination and dehumanization, and their responsibility to take action against intolerance and injustice today," Julie Heldman said in a news release.

Both the center and Cincinnati Public Schools use techniques from Mayerson Academy, a local nonprofit that works to build positive learning communities in schools and workplaces.

The program is part of Cincinnati schools' anti-bullying effort. Students identify positive traits in themselves and in each other, which prevents conflicts at school and at home. At the museum, students use those same traits to identify what makes a good leader and upstander.

David Traubert, social studies curriculum manager for Cincinnati schools, says the Holocaust museum experience aligns with Ohio standards which teach about the Holocaust in ninth grade. It also aligns with a CPS goal: to link academics, social justice, social and emotional learning and community engagement.

"That's what we want kids to think of social studies," Traubert said. "How to be better citizens. How to see and find opportunities and learn how to impact positive change, whether it be in their school, in their neighborhood, in their country or worldwide."

Earlier this month, the center received an $18 million donation, its largest yet. The anonymous gift was offered to help maintain and grow the museum, expand its offerings for family and youth leadership programming and generally expand its reach.

Next generation is 'going to change the world'

Gore told the Sharp students about her brother-in-law, who was very young when his family fled Europe for the United States. At a pier in Barcelona, she said, a sailor offered him an orange.

"He'd never seen an orange before. He didn't know what to do with it," she said.

The students peeked through the walls of the exhibit to read about Jewish kids and adults who were beaten, starved and killed. They looked up at a pile of shoes representing those who died at death camps in Poland.

This all began out of hate, Gore said. She pointed to Nazi propaganda, kids' board games and old German textbooks that depicted Jews with large noses and moneybags.

"You had to be taught to hate," she said.

Before sending the kids to the last stop on the tour in the humanity section, which focuses on social justice and empathy through interactive videos and digital activities, Gore took a deep breath and surveyed the room, looking at each of the young students in front of her.

"This is how you're going to change the world," she said. "Because your generation is our hope."

After her school's tour, Sharp eighth-grader Ava Wood said she could use what she'd learned that day when dealing with bullying in her own life.

"An upstander would go tell a teacher" if they saw someone being targeted, she said.

That's exactly what Weiss said she hopes comes from Holocaust education, that young people are more empathetic, civically engaged and connected with their community.

Weiss said she hopes to continue partnering with local schools, though she is worried about the impact of controversial Ohio House Bill 616. If it passes, she said, it could prove difficult for teachers to bring kids on field trips to the museum.

"We are hearing from teachers that they are going to be fearful to teach many topics" including history, Weiss said. The bill, which would ban teaching "divisive concepts," and others like it across the country could impact Holocaust education.

"It's a concern," she said.

The Holocaust & Humanity Center is open to visitors Thursday through Monday from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The center will host a special Yom HaShoah Commemoration for Holocaust Remembrance Day on Sunday at 2 p.m. The event is both in person and virtual.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Educators, students use Holocaust education to fight bullying