Youth in WA foster care face financial, educational barriers to earning a driver’s license

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A driver’s license is typically symbolic of a rite of passage for soon-to-be adults. It represents freedom and responsibility. But for some teens, the right to drive isn’t always guaranteed.

To a youth in foster care in Washington state, a license is a rare chance for autonomy that is often just out of reach.

Tashawn Deville is the middle school program manager at Peace Community Center, a program in Tacoma that focuses on youth education. Deville recounted her experience as a foster teen trying to earn their right to drive.

“I had people around me who didn’t want me driving because it would be too much liability for them or because they didn’t think I was mature enough to handle that kind of responsibility,” Deville wrote in a blog post from January. “Being a foster kid, in some people’s eyes, makes me untrustworthy, and I wanted to prove them wrong.”

Help for new drivers

Deville earned her license with the help from Treehouse, a Washington state-based organization that provides resources and educational assistance to youth in foster care. During its 2021-22 program year, Treehouse worked with around 6,400 youth in foster care across the state, according to Victoria Kutusz, Treehouse’s resource and operations program director.

Owning a license also lends to a sense of normalcy, Kutusz said. She added that many teens in the child welfare system can feel misunderstood and carry past trauma. Earning a license, not only grants them a newfound sense of autonomy but backs up the desire to fit in with peers.

“When you’re in a brand new community, you don’t know folks,” Kutusz said in an interview. “You’ve been removed from not just your family but your friends, your teachers, the school you knew.”

In 2018, Treehouse launched its Driving Assistance Program, which provides financial assistance to teens in foster care for driving-related costs like driver’s education, insurance, learner’s permits and test sessions. The program also allows a person in the foster care system to retake a class in its entirety, if necessary.

Treehouse’s driving assistance initiative has served about 1,500 youth in Washington since it started in 2018. The organization pays for financial requests to cover things like driver’s education, permits, licenses and auto insurance. Pierce County has had 208 participants.

The Washington Department of Transportation provides $1.1 million annually to the Department of Children, Youth, and Families, which contracts with Treehouse to provide the program.

Treehouse project manager Sarah Mazur told The News Tribune that access to getting a license is essential but difficult for youth in foster care to attain.

”A lot of the time, these youth are coming from lower-income homes or disadvantaged populations,” Mazur said in an interview. “And so I think you could just imagine the lack of access that they would have because of all of that.”

Financial costs to drive

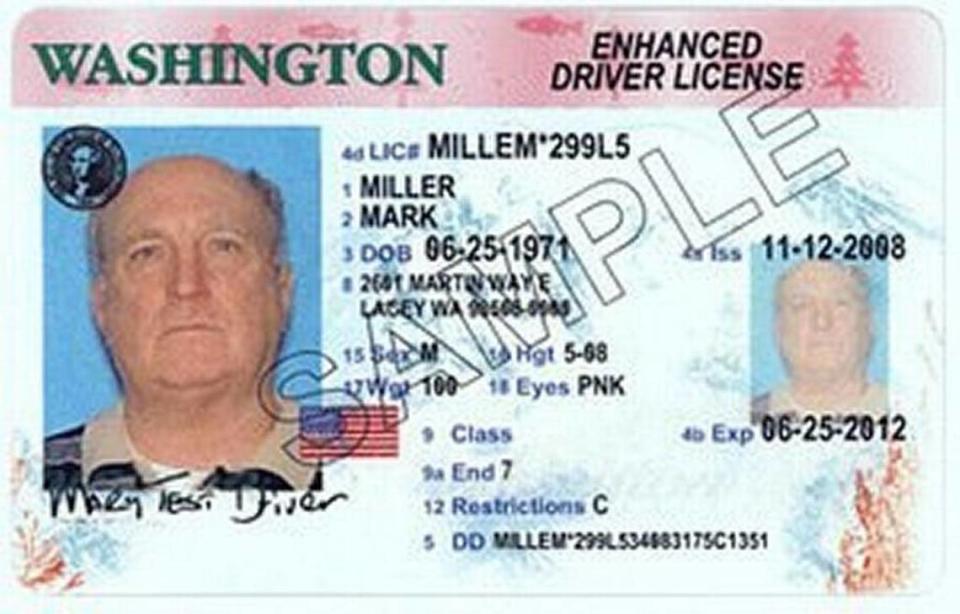

Like every other driver in Washington state, teens will still have to spend a decent chunk of change to actually apply for the actual license. The News Tribune previously reported that Washington has the most expensive driver’s IDs in the country. Currently, a six-year standard license in Washington state costs $89. California’s licenses, for instance, cost $41, and Oregon’s is $60.

But the cost of getting a license extends to driving lessons, too. Mazur said that the average cost of a driving school ranges anywhere from $400 to $700, depending on what each individual program offers, such as knowledge tests or practice exams, in its course packages.

“One of the things we were getting requests for frequently was, ‘can you help pay for driver’s ed?’” Mazur says. “We made sure that our funding ... could pay for those things that, quickly we learned, is a lot more expensive than we could cover in our current funding.”

From 2014 to 2018, Mazur said she began to notice an increase in the cost of driver’s ed courses. In 2018, Treehouse would support a foster teen with up to $500 for driving finances. But during the pandemic, costs for driving courses and tests shot up to $625 in 2020 due to an increase in driving tutoring. Today, the assistance program caps its assistance limit at a total of $750 per person. Fortunately, nobody has reached that limit, Mazur says.

Driving schools in the Tacoma area charge around $600 for full driving courses, such as A+ Driving School, Freedom Driving School and Complete Driving Experience. Additional driving lessons may cost extra.

One Tacoma school owner said her utility and service costs have increased over the past two years. Tara Dubois, owner of Complete Driving Experience, opened her school in 2021. Dubois told The News Tribune via email that she launched driving lessons over Zoom but began offering in-person lessons as health restrictions eased. Dubois says her program saw an increase in enrollment in 2022, but she’s been spending more to keep the program running due to rising prices in rent, gas for cars, insurance, maintenance for all vehicles and other operational costs.

Another integral piece to the financial side of getting a driver’s license is vehicle insurance. Treehouse’s Mazur says that because teens in foster care may have little to no driving experience and no credit history, their insurance rates could be higher when they get their license.

Mazur said she worked with youth in foster care who age out at 18 and ended up paying anywhere from $800 to $3,500 for six months of auto insurance. According to insurance website The Zebra, auto insurance for teenagers and young adults is significantly higher than for people in their 20s and those middle-aged.

The average annual cost for auto insurance in Washington:

$6,301.42 for a 16-year-old

$4,893.49 for a 17-year-old

$4,157.56 for an 18-year-old

$2,716.21 for a 19-year-old

$1,511.22 for drivers in their 20s

$1,112.68 for drivers in their 30s

$1,057.87 for drivers in their 40s

$998.70 for drivers in their 50s

$1,024.50 for drivers in their 60s

$1,283.54 for drivers in their 70s

Social network barriers

Youth in foster care often relocate, and when learning to drive, a foster teen may not be able to complete a driving course if they move to a different city. The experience and time they invest into one course may not carry over to another, Mazur says, so the teen will end up having to take a different driver’s ed program in its entirety.

Kutusz, the resource and operations program director, says that when teens enter the foster care system, they may bounce from several locations to another for a myriad of reasons.

“Even if a youth is only in one foster home, that still means they’re moving at least twice,” Kutusz says. “Once when they’re removed from their family, and then potentially, again, on reunification with their family. We also see youth who will be reunified, and they’ll do what’s called a ‘trial return home,’ and they’ll move back in with birth parents, but then sometimes that doesn’t work out. So sometimes they’re in and out of the system multiple times.”

Earning a driver’s license could help to remedy part of the burden that comes with relocation. With a car and license, a teen could possibly continue attending their same school instead of transferring to another, allowing them to hold onto established social connections and sense of “normalcy,” as Kutusz put it.

In general, continual relocations can significantly impact a teen in foster care’s mental and behavioral health, which by extension impacts their education, says Heidi Hiatt, one of Treehouse’s co-directors of its Graduation Success program.

On top of completing a course, foster teens could have learning challenges due to prior trauma, lack of mental and behavioral support and stigma surrounding foster teens in education, Hiatt says. Stigma, in particular, impacts how educators and foster parents communicate with teens in foster care due to preconceived notions about a teen’s identity. According to the National Council for Adoption, some of the most common myths surrounding youth in foster care are that they are “problem” children, they’re hard to bond with or carry too much trauma.

More support for a driver’s license

There are continuous efforts to widen the accessibility of getting a driver’s license for adolescents in foster care in Washington state. In April, Treehouse expanded all of its foster-assistance programs to all youth-age foster children across the state. Previously, the organization could assist teens in certain areas of the state, such as the Seattle metropolitan area, Tacoma, Spokane or Tri-Cities regions.

Now, all foster kids who meet the age criteria are eligible to receive support from Treehouse.

Treehouse’s broader service range will be especially important to Washington teens in rural areas who have fewer community resources to tap into or have to travel farther to attend a driving school.

Advocates are also pushing for further legislation in Washington that would bring additional financial support for foster teens to attain their driver’s licenses and improve driver safety. ESHB 5583, which was signed by the Washington Senate president and passed to Gov. Jay Inslee on April 21, would implement a driver’s education voucher program. The program would waive the average cost of a driver’s education course for those who reside in low-income households.

The bill would also dictate that adolescents ages 18 to 24 must complete a driver’s education course to earn a license, similar to the current rules for teens ages 15 to 17. The Washington Traffic Safety Commission says that motor vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death in Washingtonians ages 16 to 25. A factor that makes this a leading risk of death is lack of driving experience.

Requirements for getting a license as a teen

In Washington state, teenagers have to fulfill certain requirements to be on track for a driver’s license.

Teens aged 15 to 17 must receive their instruction permit and have one for at least six months prior to earning a driver’s license.

There are two ways to obtain one:

Pre-apply to a driver’s ed course with a parent’s signed permission.

Teenagers aged at least 15 and a half can pass the driver’s knowledge test with a parent’s approval to get their permit.

Even though teens could fast-track their way to the driver’s seat by passing a driver’s knowledge test, many opt to enroll in a driver’s ed course. All driver’s education programs have to provide students with a certain amount of training. Students must complete:

A total of 30 hours of class instruction with a maximum of 2 hours a day.

A minimum of six hours of driving practice with a maximum of one hour a day.

A minimum of one hour of behind-the-wheel observation.

The state doesn’t approve online or parent-taught courses. Aside from driver classes, teens must complete 50 hours of practice driving alongside a parent — or someone who has been licensed for five years or more. Ten of these hours should take place at night.

But for children in the foster care system, driving for dozens of hours with a legal guardian, or with a driving school instructor, may not be feasible. For instance, a legal guardian may not be comfortable driving a foster teen, or they may only have one car that isn’t available for practice driving, Mazur says.