‘Zero-fail’: How the Navy remained ready in the early days of COVID-19

PEARL HARBOR — While the eyes of the world were focused on a rapidly spreading COVID-19 outbreak onboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt aircraft carrier in March 2020, the Navy was working to quell another wave of infections on a submarine.

Five days after the USS Theodore Roosevelt's first case, a sailor stationed aboard the USS Ohio tested positive for the virus, in what became the first outbreak among crew members aboard a Navy sub.

The boat's leaders faced a daunting challenge from what was then a far-from-understood disease, with COVID-19 test kits in scarce supply and a vaccine many months away.

"We looked at this as an obstacle to readiness and a threat to our sailors," said Chris Kline, the former deputy commander of the submarine squadron that includes the USS Ohio. "We understood the nature of a submarine. It's like a giant Petri dish. If someone gets sick, lots of people get sick."

Documents obtained by the Kitsap Sun through a Freedom of Information Act request show, for the first time publicly, how the Navy thwarted the virus using early on what became a widely adopted strategy for everything from sports leagues to daycares: the bubble. Infected sailors were isolated. Close contacts quarantined. But equally important, every sailor was tested to find asymptomatic cases.

The Ohio, the oldest submarine in the Navy, was fortunate to be moored in Pearl Harbor during the outbreak, where it was possible to shuffle sailors through barracks throughout early spring 2020. Yet its example, along with other Navy outbreaks like the USS Theodore Roosevelt's, informed later deployments, like the USS Nimitz's global 11-month, 99,000-mile journey later the same year and into 2021.

The Kitsap Sun conducted interviews with sailors, from those in the enlisted ranks to retired admirals, and received documents through the Freedom of Information Act to piece together the Navy's response in those initial chaotic days of the spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

The results showed the fast-emerging bubble strategy, when combined with testing, was effective at keeping Navy ships at sea — but took a physical and psychological toll on sailors. Periods of isolation, round-the-clock face-masking and confinement to a vessel for prolonged periods were far from easy. However, those measures kept COVID-19 from spreading.

"It was rough — very tough on the sailors," said Bryan Wooldridge, a Navy doctor who served aboard the USS Nimitz. "But I think the Navy's leaders made the best decisions they could at the time."

'Out of an abundance of caution'

The Navy entered the pandemic unprepared. Four out of five Navy Component Commands — different Navy leadership groups — failed to perform a required "pandemic influenza and infectious disease exercise," according to the Department of Defense's Office of Inspector General.

Yet the USS Theodore Roosevelt's outbreak showed just how threatening the virus could be, with 1,331 crew members — about a fourth of the crew — getting COVID. Even as young as the ship's population was, 23 sailors were hospitalized, four were admitted into the intensive care unit and one sailor died. An investigation found that the USS Theodore Roosevelt's leadership was too quick to let sailors out of quarantine and allowed common areas to be open during the outbreak, which sidelined the ship in Guam.

But the USS Theodore Roosevelt's example, combined with the experience of the USS Ohio and the USS Kidd destroyer, in which at least 78 sailors caught the virus, proved scientifically that COVID could be spread through people who didn't even know they had it. Roughly half of all the cases of those who tested positive aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt never developed symptoms, according to the New England Journal of Medicine.

The Navy's challenge, like other branches of the military, was to keep sailors safe, but not at the expense of "readiness," or its ability to fight successfully in combat — even if a pandemic was raging.

"Some believed we should basically shut down the military by pausing all recruiting, in-processing, basic training, field maneuvers, and other activities critical to maintaining readiness," wrote Mark Esper, the Secretary of Defense at the time, in his memoir, "A Sacred Oath." "That was not realistic, nor was it warranted, and our outcomes over time would demonstrate this to be the case."

The USS Ohio is one of four guided-missile submarines in the Navy and one of two based in the Pacific Northwest. The boat, formerly filled with Trident nuclear missiles, was converted in the early 2000s to hold up to 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles and deploy special forces like Navy SEALs.

It may be obvious to say Navy vessels — particularly submarines — involve sailors working in tight quarters.

"Submarining is a team sport," Kline said. "You're gonna have contact with folks."

A sub, with a fraction of the crew size as a carrier, has only so many specialists in each critical position to operate, points out Henry Hargrove, a senior technical analyst at the RAND Corporation and retired submariner. Its recirculated air means the entire crew could be exposed to a virus in a short time span.

"It is possible that, if you cough all the way in the front part of the boat, it could travel all the way to the ventilation system at the back," Hargrove said. "And the submarines of Bangor cannot fail. They are zero-fail missions."

The USS Ohio had only 11 N95 respirators when its outbreak began on March 28, according to documents obtained by the Kitsap Sun. A few days later on April 2, the crew got hold of 200 expired surgical masks. The Ohio's example showed masking "likely helped slow the spread" of the virus and pushed the need for such PPE onto the Authorized Medical Allowance List, items deemed medically necessary for deployment.

The boat's sailors focused on a "whole ship sanitation" on March 28, with a second sanitation two days later. The focus on cleaning vessels has continued throughout the pandemic, even after scientists have shown that the virus transmits primarily through aerosols exhaled by an infected person.

But likely, the most important move the USS Ohio made was to use the bubble strategy, the presentation found. Any clusters of cases appeared to come from berthing areas. After the quarantine took effect, the boat's sailors suffered no further "symptomatic clusters."

In the end, the Ohio outbreak was kept to just 12 sailors on a crew of more than 130, the documents said. Of those, two cases were severe enough that they required trips to the local emergency room. One sailor developed long COVID and did not return to duty aboard the Ohio. By May 16, 2020, the virus had abated aboard the sub, the Navy presentation said.

Kline said sailors, especially those enlisted and of lower ranks, had it hardest through the onset of the pandemic. While older and more experienced sailors might go home to families, "there was no escape for our junior folks," he said — including public areas to blow off steam, like outdoor recreation facilities.

"You got used to hearing senior leadership say 'out of an abundance of caution,'" Kline said. "I worried that, when senior leadership is rigorously enforcing rules of questionable effectiveness, it could undermine their credibility with sailors."

'Mucus express': Keeping ships at sea kept cases down

In a different part of the world, the Navy faced the same problem. As the virus ravaged Italy, the first western country whose hospitals were quickly overwhelmed, leaders of the U.S. military in Europe feared a coming crisis that could cripple their ability to keep ships at sea.

"We were gravely concerned if this thing spread in southern Italy we'd have no hospital capacity to deal with it," said Adm. Jamie Foggo, then the Naples-based commander of 35,000 sailors and personnel based in Europe and Africa in the spring of 2020. "Nobody was ready for this."

Isolating sick sailors became the highest priority, from the "commanders down to the deck plates," Foggo said. But how to determine who had COVID-19 and who didn't?

The U.S. military had only one machine that could test for COVID — commonly known today as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method — for all of Europe and Africa. And it was located at a base in Germany.

Mailing swabs was too slow. So Foggo ordered some Cold War era-aircraft — the twin-propped C-26 — to fly samples to and from the base. Its mission quickly became known as "the mucus express," Foggo said.

Tests conducted onboard Navy vessels would be given to pilots who maintained a distance from those on board — a "physical separation that was safe," he said.

The bubble had to be preserved at all costs.

"We just kept them at sea," he said of the Navy's ships, including the USS Harry Truman aircraft carrier and its strike group of destroyers and cruisers. "And if they came to port, our preference was not to bring anyone on board."

Foggo acknowledged the strategy was hard on everyone. But keeping the Navy ships at sea was too important.

When case counts began mounting at home, only then did "the United States get religion," and more PCR testing machines started arriving in Europe, Foggo said. The Navy honed its strategy, one that was emulated in later 2020 throughout other industries and professions in the world, from Hollywood filmmaking to Major League Baseball.

"I think the military did lead the way," Foggo said. "There was no excuse for a ship not getting underway. Nobody wanted to see (the USS Theodore Roosevelt outbreak) happen, it was absolutely terrible."

Nimitz's bubble resulted in zero cases; but a 'rough deployment'

In April 2020, amid the backdrop of a spreading virus, the Bremerton-based USS Nimitz had the unenviable task of being the first aircraft carrier to deploy following the onset of the pandemic. The Navy could not afford another sidelined carrier.

Like on the USS Ohio, the Nimitz's leaders deployed the bubble. Sailors stationed on the carrier remained quarantined for an entire month at the Naval Base Kitsap-Bremerton pier. About 8,000 sailors across Nimitz's strike group endured the restrictions, testing and making daily evaluations to put the ship at sea COVID-free.

"It was draconian," said Wooldridge, who has since retired as a Navy physician and entered private practice in Bremerton. "But it worked. It kept the ship at sea, the sailors ready."

The bubble worked so well that there were no COVID-19 cases aboard the Nimitz during its record-setting deployment, Wooldridge said.

Wooldridge joined the crew in September 2021. Flying to Bahrain, headquarters of the Navy's Fifth Fleet where the Nimitz was sailing, he, like other crew members, remained in a Conex box for two weeks, testing twice for the virus. When those tests came back negative, he went aboard, where he spent seven more days in an enlisted bunkroom that housed around 40 sailors for further quarantine. And even once out of quarantine, he donned an N95 mask.

The ship carried convalescent plasma — the best-known COVID treatment at the time — as well as a bolstered medical staff that included an additional critical care doctor, ICU nurse, contact tracer and microbiologist for COVID testing. The ship also had aboard an additional psychologist for the mental health and well-being of the sailors.

"That ended up being far and away the hardest position," Wooldridge said.

Some sailors interviewed by the Kitsap Sun referred to the deployment as a "prison-like" environment, with the only port visits brief stops to step onto a pier for rest and relaxation.

But it was only in spring 2021, after the Nimitz returned home, when COVID-19 cases started spreading among the crew — because they were finally back among the general population, he noted.

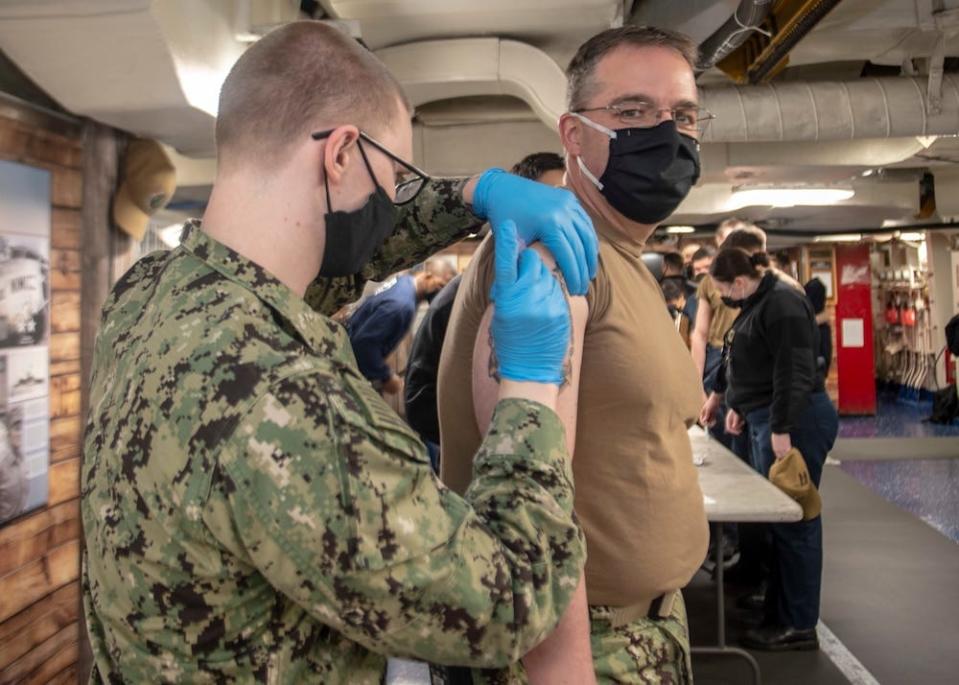

Once the Navy had a vaccine to offer sailors at the end of 2020, the service begin dialing back the harsher measures of quarantine. Wooldridge said that in 2021, the ship began to take aboard sailors positive for COVID-19, confident then they would make a full recovery. The Nimitz is preparing for its next deployment in the coming months, with the near half-century-old ship due for decommissioning in 2025.

The USS Ohio, meanwhile, resurfaced in the news when the Navy announced it had trained with the Marine Corps expeditionary forces in February 2021 near the Japanese island of Okinawa. Among the early goals: ensure the Marines can hop aboard the 560-foot-long sub quickly. The boat is often forward-deployed to Guam, where it alternates with its sister boat the USS Michigan.

The USS Ohio returned home in December 2021, a massive silver and black lei draped across its sail. The submarine, now the oldest in the U.S. fleet, is due to be decommissioned in 2026.

To date, 17 sailors in the Navy have died from COVID-19.

Josh Farley covers the military for the Sun. Follow him on Twitter @joshfarley.

Watch before you go:

This article originally appeared on Kitsap Sun: The Navy and COVID-19: How sailors weathered the pandemic's early days