The Ticket

The TicketWhy Mitt Romney can’t shut up about his money

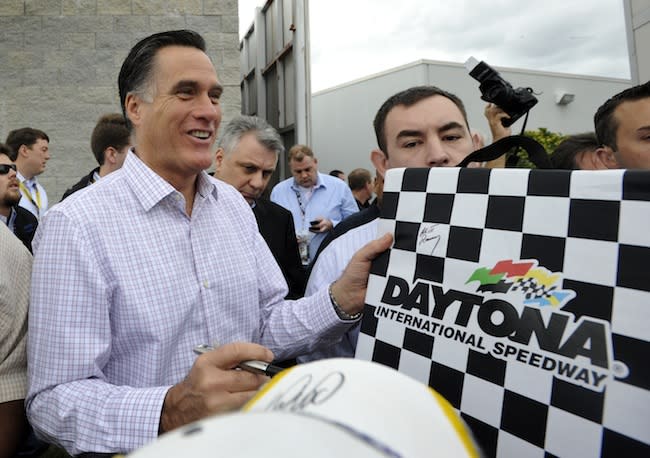

Over the space of a few months, private equity millionaire Mitt Romney has cavalierly bet a Republican rival $10,000 during a debate, enthused about the joys of "being able to fire people who provide services to me," told Detroit voters that his wife drives "a couple of Cadillacs," and said at the Daytona 500 that while he is not an ardent fan of the sport, he does have "some great friends that are NASCAR team owners.''

Each time Romney has slipped up, his Republican and Democratic rivals have seized on his comments to paint him as an out-of-touch millionaire who doesn't understand Americans' economic pain. When Fox News' Neil Cavuto asked Ann Romney about this perception on Monday, she jumped on her husband's gaffe train, saying, "I don't even consider myself wealthy, which is an interesting thing. It can be here today and gone tomorrow." Mrs. Romney was making a larger point about how material wealth is fleeting. But it's surprising that the likeable Mrs. Romney, who humanizes her husband on the campaign trail, is almost as awkward as he is when it comes to talking about their good fortune.

Romney has acknowledged that his comments have hurt him, yet he keeps on going there. "It's really mind boggling, because he seems so disciplined in so many ways, that some of these things would come out of his mouth," Republican strategist Keith Appell told the New York Times.

"I'm trying to do better and work harder," Romney said in Michigan.

That might be part of the problem. Research suggests that the more Romney tries to not talk about his wealth, the more likely he is to do just that. The human mind is perversely drawn to fixate upon the subjects we most want to avoid, especially when under stress.

Authors and athletes have known this intuitively. In Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Idiot, the childlike and excitable protagonist Prince Myshkin is told by his sweetheart that the worst thing he could do at an upcoming party is to break an expensive Chinese vase. Myshkin becomes consumed by the thought that he must not break it, and makes a point of sitting as far away from the vase as possible. But "an ineradicable conviction had taken possession of his mind that, however he might try to avoid this vase, he must certainly break it." And of course, he does--upsetting the vase near the end of the party with one of his wild gestures.

In a real-world example, former St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Rick Ankiel had to give up pitching after he became fixated by--yet unable to prevent--his sporadic wild throws. He called these pitches "the Creature," while others have termed it "Steve Blass disease," after the Pirates' pitcher who suddenly lost his ability to throw strikes in the 1973 season.

The Harvard social psychologist Daniel Wegner began to examine what he called this "perverse psychological process" in a 1987 experiment, in which he told people not to think of a white bear before asking them to talk aloud for several minutes. Participants who were told not to think of the white bear mentioned it once a minute on average, showing that people are not very good at suppressing even very mundane thoughts when specifically asked to.

This is because our brain is always helpfully looking around for the very worst things we could do or say in any given situation, and then actively trying to suppress them with other, more appropriate thoughts and actions. The process has two parts--the unconscious, automatic monitoring of our forbidden thoughts, and the conscious, effortful way in which we distract ourselves from it. So when a person is trying not to think or talk about something--say, to pick an example at random, his personal wealth--he needs to both monitor the forbidden thought and distract his mind with other thoughts. This is called the "ironic process," and it usually works, otherwise we would always be blurting out our secrets and insulting our loved ones.

"By and large this can operate very well. But all bets are off when there are other demands in the situation that require a great deal of cognitive effort," Ralph Erber, a DePaul professor who co-wrote several studies on the ironic process with Wegner, told Yahoo News. When a person is under stress, the automatic process that monitors the forbidden thought still works well, but the conscious part that finds him something else to think about is no longer running smoothly. Public speaking is just the sort of stressful situation to muck up the distraction part of the equation. "That really impairs the part of the process that would help Mr. Romney or anyone else keep thoughts about money out of consciousness," he said.

"This simple process of trying to keep a thought out of consciousness can become a borderline obsession," Erber continued.

But there are ways to overcome the problem. Wegner wrote in the American Psychologist journal last year that the best treatment may be "avoiding the avoiding," or, in reference to his own experiment, "setting free the bears."

This happens to be the advice of Brad Phillips, a former journalist who is now a media consultant. He wrote not long ago that instead of unconvincingly pretending to be a regular Joe, Romney should embrace his wealth as other candidates, like New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, have. They've argued their wealth means they can't be bought by special interests. "It's time for Romney to start running as the person he really is: a rich guy," Phillips wrote on his blog. "Instead of hiding from his wealth, Mr. Romney should start explaining why his wealth will help the American people."

Romney's campaign has occasionally trotted out this tactic, but if it doesn't work, there are other treatments to try. Talking or writing as much as possible about the suppressed topic helps the unconscious stop monitoring it so assiduously and thus pushing it up into our thoughts.

"If he spends some time before he talks ... thinking about money all he wants to the point that he's literally exhausted it's less likely to enter into conversation later on," Ralph Erber, the DePaul professor, told Yahoo News.

As in most things, practice also helps. "People who manage to chronically suppress things about themselves get good at it," Erber said. "Over time this is likely to get better."

Another potential cure is hypnosis. In 1996, an experiment found that patients who were told to forget the name of their favorite car were less likely to remember the car after the hypnosis session. But many people do not respond well to hypnosis, and it's unclear if it would benefit Romney.

As Erber said, "I really wouldn't bet the election on it."

More popular Yahoo! News stories:

• On jobs, former Obama aide Goolsbee warns against irrational exuberance

• Mitt Romney faces challenging primaries in Mississippi and Alabama

• Ad race of 2012: Obama spot tops most frequently aired political ads

Want more of our best political stories? Visit The Ticket or connect with us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, or add us on Tumblr. Handy with a camera? Join our Election 2012 Flickr group to submit your photos of the campaign in action.