80 years ago, Tuskegee Airmen trained at Selfridge Airfield to fly in World War II

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Eighty years ago, military planes zoomed back and forth across Michigan's skies like streaks of red-tailed lightning with the purring thunder of a spinning propellor.

But for the first time in U.S. history, African American pilots sat in the cockpits.

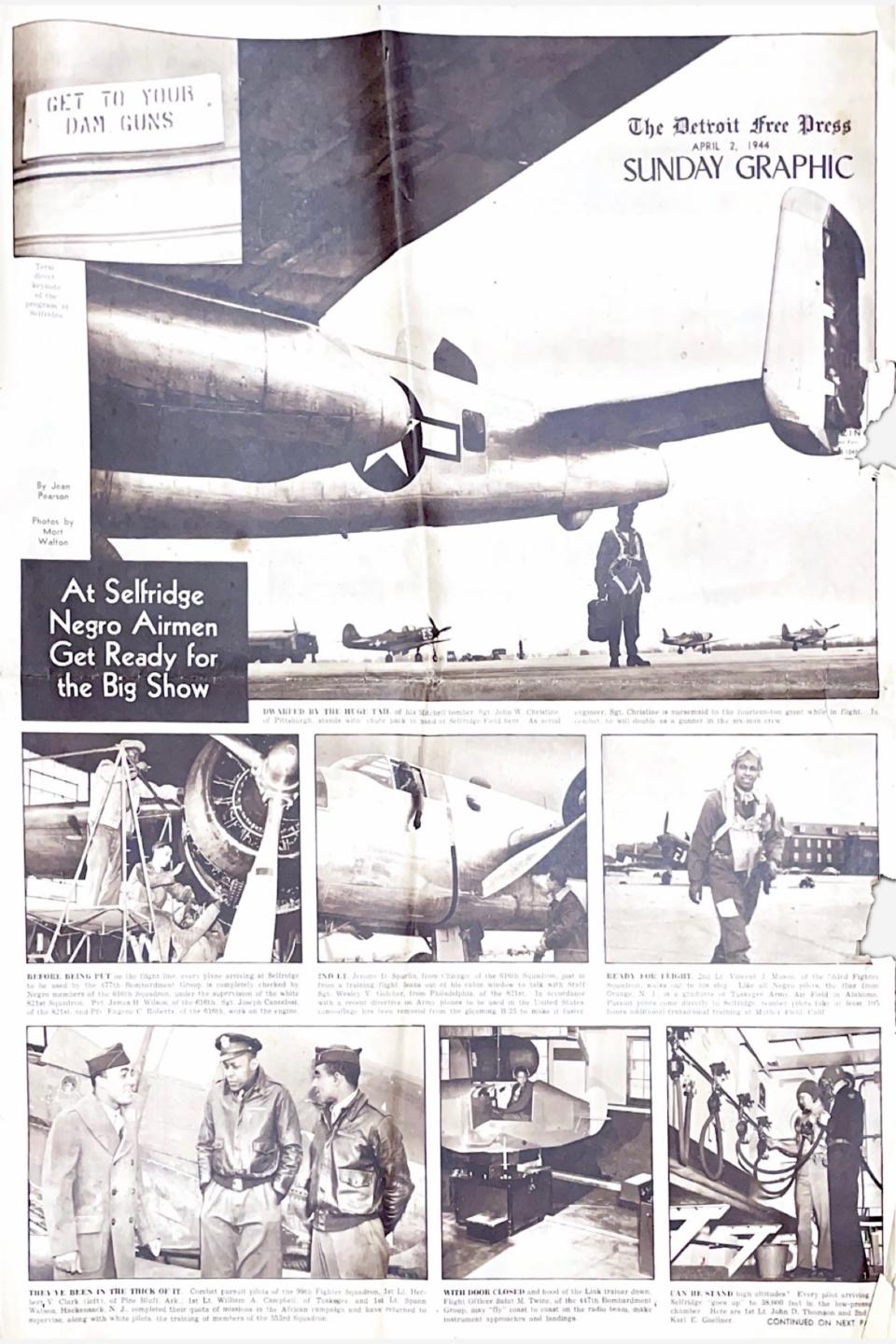

The Tuskegee Airmen — made up of the 332nd Fighter Group, the 477th Bombardment Group and up to 16,000 of the individuals who supported the pilots' training — were the first Black pilots and airmen in the U.S. military during World War II. For a time, they trained here in Michigan, zipping above metro Detroit and proving the era's societal prejudices wrong.

Today, families, historians and the Tuskegee themselves look back at their war-torn days with dignity, not just for fighting battles overseas but fighting battles back home — and winning.

"Their impact started the Civil Rights Movement. They set a standard for which you could not deny their value as Americans," said Brian Smith, president of the Tuskegee National Historical Museum and son of an African American solider in the 92nd Infantry Division.

The beginning of the Tuskegee Airmen

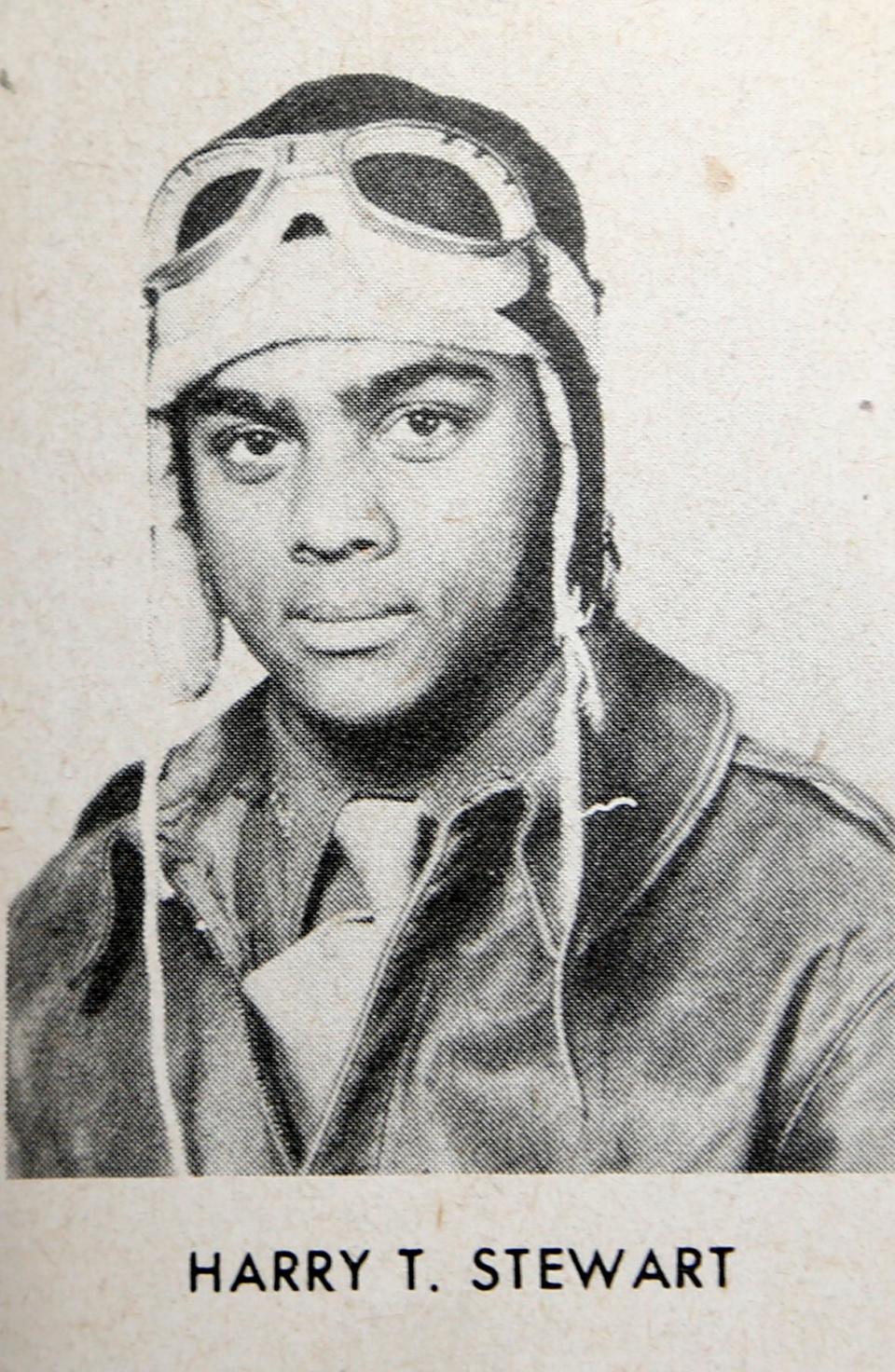

When the United States entered World War II and began drafting young men in 1941, many African American men, such as Lt. Col. Harry Stewart Jr., rushed to their local draft board to volunteer.

Stewart, now approaching his 100th birthday later this year, grew up in New York next to what we now call LaGuardia Airport and was fascinated with planes from a very young age.

“I used to go down to the field and stand at the boundary of the airport and watch the planes take off and land and fantasize about being a pilot on a plane," said Stewart. "Then, in 1941, World War II came along, and I felt morally bound and very patriotic from the standpoint of ... I wanted to volunteer and try to get in as soon as possible.”

Like Stewart, many young African American men were motivated to join the Army Air Corps because they dreamed of flying while others dreamed of respect. "But all of them wanted to fight for their country," said Smith.

Aspiring aviation cadets from around the country were sent to Tuskegee Army Airfield in Tuskegee, Alabama, to learn the basics of flying before transferring to other bases to learn skills like gunnery, cross-country navigation, and how to fly operational aircraft as opposed to training aircraft — hence their move to Selfridge Army Airfield, about 30 miles from Detroit.

At Selfridge Airfield

By 1943, U.S. troops were preparing to invade southern Italy and north Africa, meaning that the Tuskegee Airmen would very quickly need to learn how to fly over marine-like conditions with nothing but water as far as the eye could see.

And where better to simulate that environment than our very own inland seas?

“One of the reasons they wanted to bring them up here was that when they were in the Mediterranean, they’d be flying over water a lot. The climate (of the Great Lakes region) had similar characteristics and we had a lot of water for them to practice flying over,” said Steven Mrozek, executive director of Selfridge Military Air Museum.

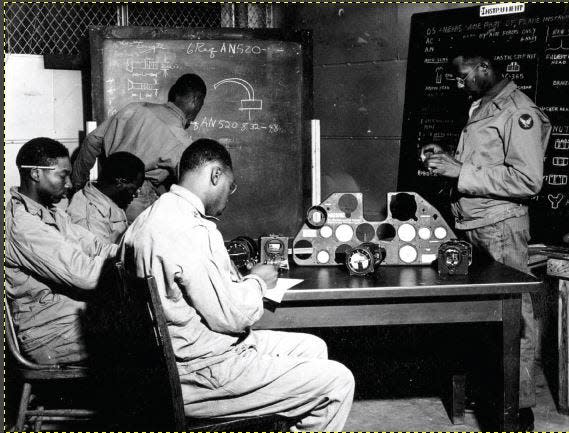

On base, the Airmen spent half of each day soaring their P-40 Warhawks and P-39 Airacobras over the Lakes or flying to remote areas to practice gunnery. The other half of their day, they'd hit the books, studying navigation, meteorology, armament and maintenance.

As described by Stewart, who trained at Tuskegee and never made it to Selfridge, “Training was so arduous that most of your time was taken up by flying or training, but the little bit I did get out … I would go over to Tuskegee Institute on a Sunday or a day off, there may be dances or parties or something else, so that’s what I did for social outlet.”

Once the Airmen at Selfridge managed to get leave, they'd venture down to Detroit and surrounding neighborhoods or travel as far as Chicago for a weekend. Or they'd meander on over to a speakeasy — a guilty pleasure for many during the Prohibition era — just a couple miles away in Mount Clemens.

“They were actually in their element here. (Before) there wasn’t a big group of African Americans, but in Detroit, there was. They loved it,” said Smith. “This was the place to be, socially. But there was still that segregation on base.”

In a country still deep into Jim Crow laws, Selfridge Airfield had a particularly discriminatory and segregated environment. Experienced airmen and other military officers were treated as trainees, and against Army regulations, were additionally excluded from the on-base officers' club. The African American airmen founded their own Black officers' club, but the inequalities between the two were evident.

The end of the Tuskegee's time at Selfridge

The conflict at Selfridge came to a climax on May 5, 1943 — as racial tensions were climbing just over a month before the Detroit race riot in 1943 — when Col. William Colman, a commandant of the base, drunkenly shot Pvt. William MacRae, an African American solider assigned to chauffeur him, after Colman refused to be driven by anyone other than a white soldier. He was court-martialed but only reduced in rank, triggering protests concerning the leniency of his sentence. As a result, many Tuskegee Airmen were transferred to Godman Field in Fort Knox, Kentucky.

“We were learning about what actually ‘caused’ (the shooting) at the same time that we were protesting segregation," said Smith. "They may have said, ‘This might be the spark that ignites the gasoline, so let’s get these guys out of here before we have a riot. Because if we have a riot, folks are going to come from Detroit to help them,’ so they shipped them out immediately.”

For those who remained at Selfridge Airfield, life continued as it did before.

The 553rd Fighter Squadron, which trained replacement pilots for the 332nd Fighter Group, was the last group to train at Selfridge Airfield before moving to Walterboro Army Airfield in South Carolina in early May 1944.

But the segregation didn't stop at Selfridge. Tuskegee Airmen who were moved to train elsewhere in the U.S. and fight overseas faced battle after battle with racism. Some Airmen even recalled seeing German prisoners of war with more freedom than the Black pilots on base. But the Airmen kept fighting.

Overall, just under a thousand men flew as pilots for the 332nd Fighter Group and the 447th Bombardment Group and they were crucial to winning the war in Europe. The 332nd Fighter Group set an unprecedented record flying 200 of their 205 bomber escort missions without losing a bomber to enemy aircraft, earning them over 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses and a Presidential Unit Citation, as well as the claim "Never Lost a Bomber."

More: Detroit woman, 87, writes book about her life that began in Black Bottom

After World War II

Coming home, many of the Tuskegee Airmen expected more respect for their sacrifices made during the war and were disappointed to return to their country's unchanged segregated ways.

Fortunately, not everyone denied their accomplishments.

In 1948, President Harry Truman signed an executive order that banned segregation in the military, making the U.S. Armed Forces the first institution in the U.S. to end the physical separation between Black people and white people.

The Tuskegee Airmen continued to do great things, some continuing their time in the military and others becoming doctors, lawyers, teachers, businessmen and much more. Several, like Stewart, tried to pursue flying as commercial pilots, yet all but one were rejected for their skin color.

But through the years, many let their bitterness go, Smith said, only reminiscing on their cockpit days with pride and honor.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Tuskegee Airmen trained at Michigan's Selfridge Airfield during WWII