A public health employee predicted Florida's coronavirus catastrophe — then she was fired: 'This is everything I was trying to warn people about'

“More people are gonna die,” Rebekah Jones wrote to her mother and sisters on Facebook. It was April 26, a warm spring Sunday in Tallahassee, Fla., and she was just finishing work at the Florida Department of Health, where she was managing the state’s much-praised coronavirus dashboard, which she had also created.

“I feel sick,” the 30-year-old doctoral student continued.

The exchange marked the beginning of an exceptionally turbulent period for Jones, who was demonized by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis as a rogue employee while also being celebrated by his detractors as a brave truth teller willing to stand up to political power.

In a whistleblower complaint Jones filed last Thursday with the Florida Commission on Human Relations, her attorneys alleged that she was fired by the state’s Department of Health for “refusing to publish misleading health data.”

DeSantis’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

“We wanted to be wrong,” Jones told Yahoo News. “What we’re seeing right now is actually far worse than what we anticipated.” Back in May, DeSantis’s combative press secretary dismissed as “alarmist” new projections showing the state suffering 4,000 mortalities from COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Florida now has more than 5,000 coronavirus fatalities.

Of the many supposed errors DeSantis has allegedly committed in the course of the pandemic, his administration’s firing of Jones may prove the most symbolic to those who see it as a Trumpian rejection of numbers that don’t look good.

Six months since the coronavirus is believed to have entered the U.S., Florida is recording some 10,000 daily coronavirus cases, more than most countries, and Jones’s dire predictions appear to have been borne out. Her rapid rise and sudden fall from grace in the Florida Department of Health illustrate the larger tension between science and politics when it comes to pandemic response. Initially hailed as a hero for building an easy-to-comprehend dashboard, Jones claims she was pushed aside when the numbers clashed with DeSantis’s desire to reopen the state.

Last weekend, the state recorded more coronavirus infections than the entire continent of Europe. “This,” Jones says, “is everything I was trying to warn people about.”

On Jan. 23, long before most Americans were even aware that a new virus was spreading from China, Johns Hopkins University announced the launch of a coronavirus dashboard that had been created by Lauren Gardner, a young civil engineer.

“This is something I think we should watch,” Jones told superiors at the state health department on Jan. 24. At the time, she was head of the department’s geographic information system division, which mapped how hurricanes like Michael battered the state.

Jones, who had been a journalism student at Syracuse University in New York and then studied climate science at Louisiana State and, later, Florida State, had joined the state health department in 2018 while still pursuing her doctorate in geography. As the coronavirus spread from China to Europe and the Middle East, Jones pestered her superiors to be allowed to create a Johns Hopkins-like portal for the state. She says they told her it wasn’t necessary, as it would only frighten people.

Finally, on March 12, she got a call from Carina Blackmore, the head of the health department’s infectious disease division.

“They wanted a dashboard, and they wanted it up today,” Jones says Blackmore told her. The task would have been impossible, except Jones had prepared mock-ups of the dashboard. “I had it up in two hours.” (Blackmore declined to speak to Yahoo News for this article, as did all other health department officials contacted.)

Software engineer Olivier Lacan, who lives in Orlando and volunteers for the COVID Tracking Project, remembers when he first encountered Jones’s creation, only to be astonished by the ease with which it allowed him to access information about the coronavirus. “It really felt like plugging into ‘The Matrix’ in some ways,” Lacan says. He remembers thinking, “I can’t believe I have access to this.”

Lacan says Florida stood out, for once not as the butt of jokes but as an example of getting it right. “Everyone had data. It was just a question of how much of a mess it was,” he told Yahoo News. “California was a tragedy for months.”

Others noticed too, including Dr. Deborah Birx, the coordinator of the White House coronavirus task force. “That’s the kind of knowledge and power we need to put into the hands of American people,” she said of the Florida dashboard on “Face the Nation” on April 19, “so that they can see where the virus is, where the cases are, and make decisions.”

A site Jones initially figured might garner a couple of thousand views overall had registered 100,000 unique visits within a week of launching, as worried Floridians checked whether the virus was making its way down from New York and New Jersey, which some said it would inevitably do. Others said the heat and humidity of Florida would keep that from happening.

The heat-and-humidity hypothesis was especially popular in a White House eager to declare victory over the pandemic and have the country begin a return to normal. At a White House coronavirus task force briefing on April 23, President Trump trotted out William Bryan, head of the science and technology division at the Department of Homeland Security, who described the results of a recent government study.

“Our most striking observation to date is the powerful effect that solar light appears to have on killing the virus,” Bryan said. “We’ve seen a similar effect with both temperature and humidity as well.”

By this time, governors across the Southeast were indicating their impatience with lockdown measures they had imposed. Among them was DeSantis, who until 2017 had been an obscure conservative congressman. Deftly using constant appearances on Fox News, he had gotten Trump’s attention, using the president’s endorsement to become governor of the state in 2018.

“We were really on fire in many ways until we hit this roadblock,” DeSantis said of Florida’s economy on an April 20 conference call announcing a reopening task force. He vowed that Florida would “bounce back in a very thoughtful, safe and efficient way.”

DeSantis’s reopening task force met for the second time on April 22, the day before the White House announced the heat-and-humidity study results. The Florida task force was supposed to submit its final recommendations that Sunday, April 26, but there was little uncertainty about what DeSantis planned to do.

On April 24, Jones was told to begin preparing the dashboard for reopening. Blackmore, the state epidemiologist, asked her to prepare a county-by-county “scorecard” that included diagnostic test positivity rates, hospitalization data and other factors that would help determine whether that county was ready to emerge from lockdown orders. Blackmore wanted to share the new feature with the state’s deputy health secretary, Dr. Shamarial Roberson, over the weekend.

“They want this live, like Sunday,” Blackmore told Jones, according to Jones’s recollection. Jones also discovered she would be receiving coronavirus data only once a day from now on, as opposed to twice. “Leadership wanted to take a more active role in reviewing the data before it was made public,” Jones told Yahoo News. She says officials from the governor’s office were involved in those reviews.

A current employee of the Florida Department of Health, who asked for anonymity because of concerns over professional retaliation, said the department has been plagued by politics and inexperience. “None of them have worked during dark sky weather,” the department employee said, speaking of the top officials in the department.

The employee said the goals of public health have been made subservient to DeSantis’s political consideration. “When DeSantis came onboard, it became very much what the governor’s office wanted,” that employee told Yahoo News. “They were running the show,” he added. “It was politics.”

Jones presented her reopening scorecard to Roberson on Sunday morning, which made it clear that very few rural counties had met reopening criteria, even as DeSantis promised that a statewide reopening was only days away. “I don’t like this,” Roberson said, according to Jones.

Jones alleges that Courtney Coppola, the departmental chief of staff, told her it would be a “political nightmare” to allow urban counties like Broward and Miami-Dade to reopen while keeping rural counties like Jackson, Franklin and Suwannee closed, even though those rural counties were showing high infection rates. (Those counties were also Republican strongholds, with 77 percent of the voters in Suwannee County and 65 percent in Franklin County voting for DeSantis in 2018.)

Some of those rural counties had positivity rates as high as 20 percent, whereas they needed to meet the 10 percent benchmark for reopening. Some also had outbreaks in nursing homes, which drove up infection rates. “They didn’t think that should eliminate its ability as a county to reopen,” Jones said of the nursing home outbreaks in particular.

She said Roberson issued an unambiguous directive: “Find a way to get rural counties to reopen.” Coppola, for her part, allegedly explained to Jones that a partial reopening “is going to really harm the public image of the governor,” according to Jones’s recollection of the conversation and detailed in her whistleblower complaint.

Jones complained to some of her superiors in an email that morning, writing that she was being told to say counties could reopen and expressing discomfort at that order. Blackmore wrote back quickly. “I think we may need to hold different size counties (or at least the small ones) to different standards,” because, Blackmore explained, people there would “naturally socially distance most of the time.” She did not provide evidence for that assertion.

Jones said she was ordered by Roberson to simply put a “yes” or a “no” next to a county’s reopening outlook, without providing the kind of data-bolstered rationale she had figured would go into the decision. Roberson left for a meeting, so Jones evaded that order. (A private vendor would eventually complete the work Roberson and Blackmore were looking for.)

Going home that evening, Jones wrote to her family on Facebook about the personal disgust she felt at what she perceived as being asked to manipulate data, as well as the danger such a manipulation could prove to unsuspecting Floridians.

“Honest to God, for the first eight weeks I had faith in what we were putting out, in what I was doing to inform people,” Jones told Yahoo News. “That changed really quickly.”

DeSantis announced on Wednesday, April 29, that, with the exception of Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties, Florida would be entering the first phase of reopening the following Monday. “We obviously need an economic recovery,” he said, essentially reprising the argument an increasingly impatient Trump had been making for weeks.

Returning to work after the previous Sunday’s encounter with Roberson, Jones saw changes to the dashboard being made that she says were preparations to ensure that data would not call DeSantis’s plan into question. For example, that Tuesday afternoon — less than 24 hours before DeSantis would announce the reopening of the state — a state epidemiologist named Samuel Prahlow emailed Jones to say that unless someone gave a Florida-based address when being admitted to the hospital, they should not be counted as having been hospitalized for the coronavirus.

“I don’t think we need to show this on the dashboard,” he wrote.

Jones would come to document several changes made to the dashboard in the days before reopening, along with those regarding rural counties and out-of-state patients. Most crucially, she alleged that positivity rates were depressed because the number of new infections was divided by the negative lab tests, not people testing negative. Because coronavirus patients are tested many times, using tests administered instead of people tested as the baseline made the situation seem better than it actually was, she claims.

There were other changes to the data presentation as well, Jones has alleged. For example, when a patient tested positive, instead of simply reporting the results as soon as they were available, the department created case files, slowing the reporting. Jones believes this was intentionally done to bury any spikes in positive cases in a needless layer of bureaucracy.

She also alleges that some reopening criteria were changed so that weekly data, not daily data, was considered. That also had the effect of smoothing out any infection increases, Jones says.

About two hours after receiving Prahlow’s email, Jones wrote to someone who worked at a major vendor of geographic software. “I wanted to ask you if there are any positions available you think I’d be suitable at,” she wrote. “I’m being asked to fudge numbers in support of a political agenda, and that is not something I am willing to do. I may have to exit.”

The following Monday, May 4, Florida began the first phase of its reopening.

The morning of Florida’s reopening, Jones received an order from Scott Pritchard, the state epidemiologist then in charge of Florida’s coronavirus response. “This whole site needs to come down,” she said he wrote her in an email following a Miami Herald inquiry about whether the state had actually experienced some measure of community spread in late 2019, well before anyone assumed the virus had arrived in Florida. (In her whistleblower complaint, Jones describes how Pritchard came into her office and issued the same command; Pritchard, who abruptly left the health department earlier this month, did not respond to emails to his personal account.)

Jones refused. “I’m not taking ‘the whole site’ down,” she wrote in a lengthy email to her direct supervisor, Craig Curry. Referencing the order from Pritchard, she said she was “not pulling our primary resource for coronavirus data because he wants to stick it to journalists” asking questions. “If it’s in the dashboard, it’s public. Period.”

Although Curry agreed with Jones, a consultation with Roberson, Blackmore and Pritchard — who were his superiors — apparently led him to conclude that Jones had little choice but to at least restrict public access to the raw data. “Disable the ability to export the data to files from the dashboard immediately,” he wrote about two hours after Jones sent her defiant email in response to Pritchard. That order to lock the data away, instead of outright deleting it, apparently came from Blackmore.

This time Jones complied. An hour later, however, after the site malfunctioned, Jones says Blackmore asked her to restore the data. Still, the damage was done, in her view, both to the integrity of the dashboard and to her standing with her bosses.

On May 5, Jones was pulled off the dashboard she created. She says she now watched as the work was “not just undone but destroyed.” The dashboard first crashed on May 7, and for several days after that. Jones says Curry asked her to repair it.

“I’m thinking about filing a whistleblower complaint about how I’m being treated, the dashboard mess, etc., for gross mismanagement,” she wrote to Curry on May 14. They met in his office the next day; she says he urged her not to file such a complaint.

She didn’t, but wrote to her mailing list — which included researchers and members of the media — detailing her concerns with how the dashboard was being run. “As a word of caution, I would not expect the new team to continue the same level of accessibility and transparency that I made central to the process during the first two months,” Jones wrote, doing little to hide her bitterness. “They are making a lot of changes. I would advise being diligent in your respective uses of this data.”

The following Monday, she was fired from her job.

The irony of Jones’s situation is that she did not become famous until after she was no longer employed. Two hours after she was fired, an article ran on the news site Florida Today: “As Florida re-opens, COVID-19 data chief gets sidelined and researchers cry foul.” The accompanying photo showed Jones looking a little uneasily at the camera, her face framed by blond curls. Behind her were two computer screens showing the dashboard she created.

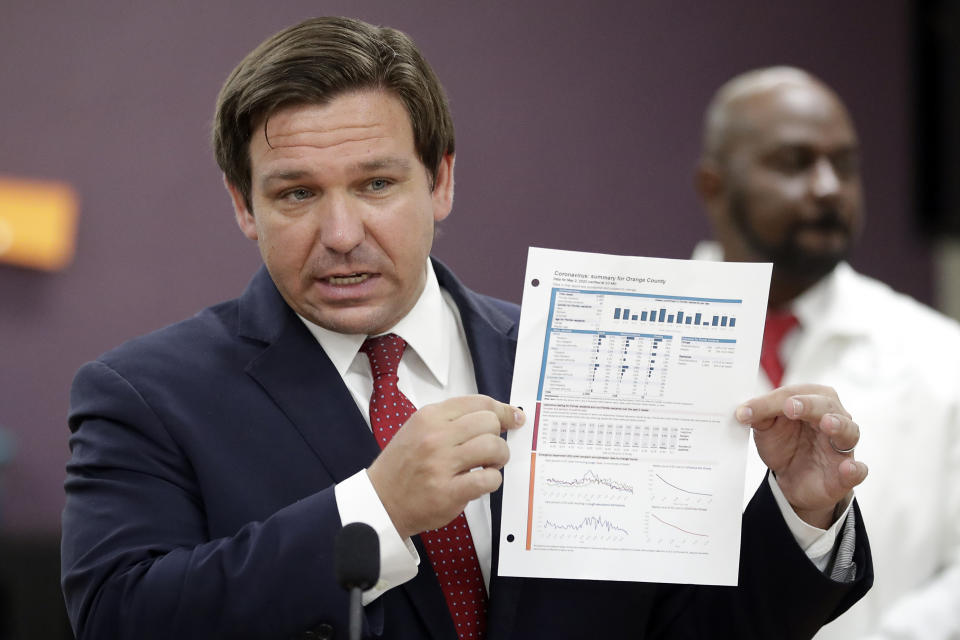

At first, the often prickly governor tried to downplay the Jones affair. The day after the Florida Today article was published, a reporter asked DeSantis about Jones’s allegations at a press conference. “It’s a nonissue,” DeSantis said before quickly moving on. His press secretary subsequently issued a statement describing Jones as having been fired for “insubordination,” and denied any data manipulation.

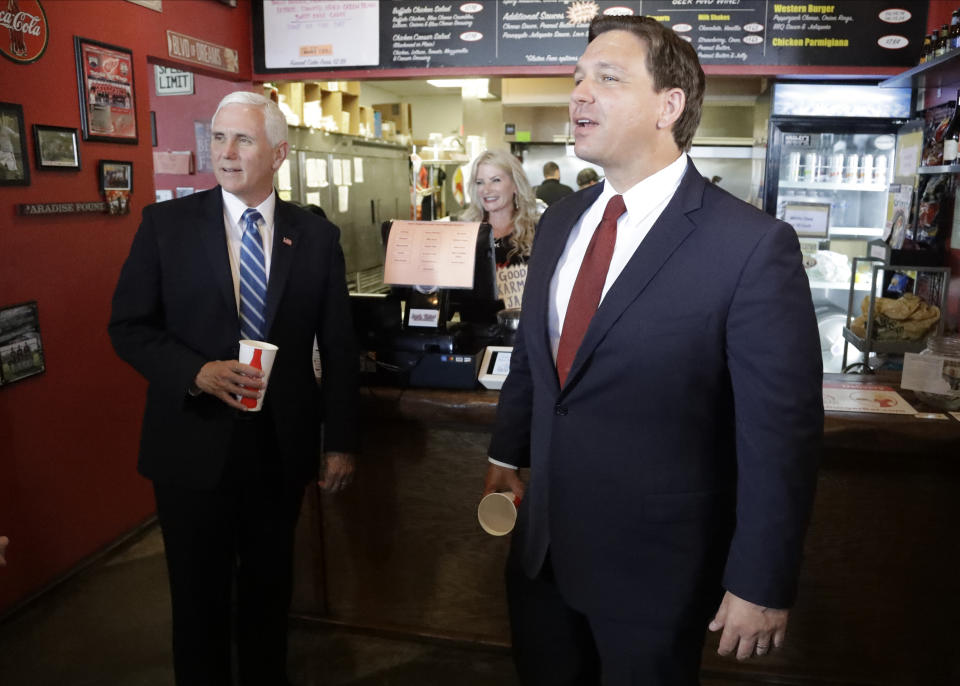

But it was an issue, as became apparent in a matter of hours. When Vice President Mike Pence visited Orlando the next day, DeSantis addressed the issue again, this time at greater length. He attacked Jones’s credibility, pointing out that she is “not a data scientist,” and alluded to her personal life, telling reporters she was “under active criminal charges in the state of Florida for cyberstalking and cyber sexual harassment. I asked the Department of Health to explain to me how someone would be allowed to be charged with that and continue on.”

Tipped off by DeSantis, reporters quickly dug up the criminal records, including an unflattering mug shot of Jones, who had been arrested for stalking a Florida State undergraduate with whom she’d had a contentious relationship. She was also accused of publishing “revenge porn” about him, a reference to what one outlet described as a 342-page “manifesto” that included “graphic details on alleged sexual encounters” between Jones and the student, as well as “screengrabs of texts and sexts she claims were between the two” and “photos and X-rated paragraphs about their trysts.”

Jones says that at the time of that relationship she was “in a vulnerable, lonely place,” having separated from her husband, with whom she has since reunited. She says the relationship with the student “turned very volatile.” She adds that writing what was called a “manifesto” about the relationship was, in fact, intended as an act of “healing.”

One leading female Democrat in Florida says she was discomfited by the allegations against Jones. But, that Democrat adds, “I don’t think she has any incentive to lie.”

What had been the battle between Florida and the coronavirus now became a battle between Jones and DeSantis. Jones was proving inconvenient for the governor, who was clearly trying to use his success over the coronavirus as a potential argument if he sought the White House in 2024, as many expected him to do.

Conservative media were eager to celebrate the promising young conservative.

Jones frustrated this narrative by refusing to remain silent. Using funds from a GoFundMe campaign launched by her sister, Jones started building a dashboard entirely on her own. While she no longer had access to “raw” data, enough was publicly available for her to design a portal of her own.

“I did build it,” she says of the tracker. “And I’ve rebuilt it. And I rebuilt it better.” The tracker went live on June 12, to national attention, serving as a kind of rebuke to Florida’s original dashboard, which she says became less useful, and less functional, after she was pulled off the project. Her dashboard appears to include more details, such as statistics about pediatric cases, prison outbreaks and nursing homes.

The day before the new project was revealed, Florida recorded 1,698 new cases, which was then a single-day record for the state. But an increase in infections was expected with reopening, and neither DeSantis nor his supporters seemed especially worried about Florida or other states undergoing further spikes.

The problem was that the numbers kept rising throughout June and into July. On July 12, Florida recorded more than 15,000 new cases, an inauspicious record for any state on a single day. And yet DeSantis continued to push his state to reopen, depicting the spike in both infections and deaths as merely a “blip.”

Asked which scientists DeSantis is taking instruction from, state Rep. Dianne Hart, a Democrat from Tampa, laughed. “You’re trying to be funny,” she told Yahoo News. “I don’t know who he is listening to.”

Jones, meanwhile, has continued to speak out on the website of her new dashboard, where she can be as political as she wants, and on Twitter, where she calls herself an “insubordinate scientist” with pride. She maintains that fealty to the data would have resulted in the conclusion that it was too soon to reopen — that hospitals would fill up, that people would die and that many parts of the state would have to close back up again.

“In my conversations with Dr. Jones, she has proven to be an expert driven by transparency and openness,” said Florida’s agriculture commissioner, Nikki Fried, a Democrat elected to the office in 2018 and an unstinting critic of DeSantis. “The character assassination ordered by the governor on this young woman, data scientist and whistleblower was straight out of the Trump playbook. We have a saying here in Florida: Sunshine is the best disinfectant. Dr. Jones is letting the sun shine on Florida’s corrupted COVID-19 data.”

Hoping for a compelling narrative, DeSantis got one, only it was not the narrative he sought. “Everything that we had, every model that we had run, said that this is exactly what’s going to happen,” Jones told Yahoo News, just days before Florida broke another record with 156 new coronavirus deaths on July 15.

“This was inevitable, unfortunately.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: