Almost 7,000 heat-stressed corals have been returned to nurseries off the Florida Keys

By late morning on Nov. 21, every piece of heat-stressed coal evacuated from the Florida Keys to Sarasota following last summer’s unprecedented underwater heat wave had been returned home.

Most of the coral is still being monitored in land-based nurseries, such as the three Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium operates in the Keys, as expert coral reef restoration researchers continue the process of returning those corals to off-shore nurseries.

Jason Spadaro, Mote’s coral reef restoration research program manager, said, “For the most part, the vast majority of corals that we have on land right now are looking phenomenal.”

Just before Thanksgiving, almost 7,000 corals that had been cared for at Mote Aquaculture Research Park were returned to Mote’s offshore nurseries at Sand Key, Looe Key, Islamorada, and Key Largo, Spadaro said.

The return effort started in late October, after thousands of specimens of heat-stressed coral had been cared for and nurtured back to health at Mote’s aquaculture park, The Reef Institute, a coral research and restoration facility in West Palm Beach and elsewhere for roughly three months.

A cooperative coral rescue effort

The corals were moved through a massive, cooperative effort of coral restoration scientists, government agencies and local businesses that Michael Crosby, president & CEO of Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium, likened to a cross between Noah’s Ark and the World War II evacuation of allied troops from Dunkirk.

Staghorn and Elkhorn coral were particularly impacted by warm water and subsequent bleaching in a historic climate event that drew international attention after an underwater sensor in Florida Bay recorded a temperature of 101.5 degrees on July 24.

Those nurseries are key to Mission Iconic Reefs, a $100-million effort by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and seven partners to restore roughly 3 million square feet of coral reefs on seven iconic sites along the 300-plus mile long Florida Reef Tract.

Hand-feeding coral to build strength

Corals are colonies of tiny polyps that eat plankton. They live in a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae algae, which feed on coral waste and carbon dioxide and provide the coral oxygen and organic products of photosynthesis.

Increased water temperature for an extended period of time can prompt bleaching – when the coral expels the zooxanthellae.

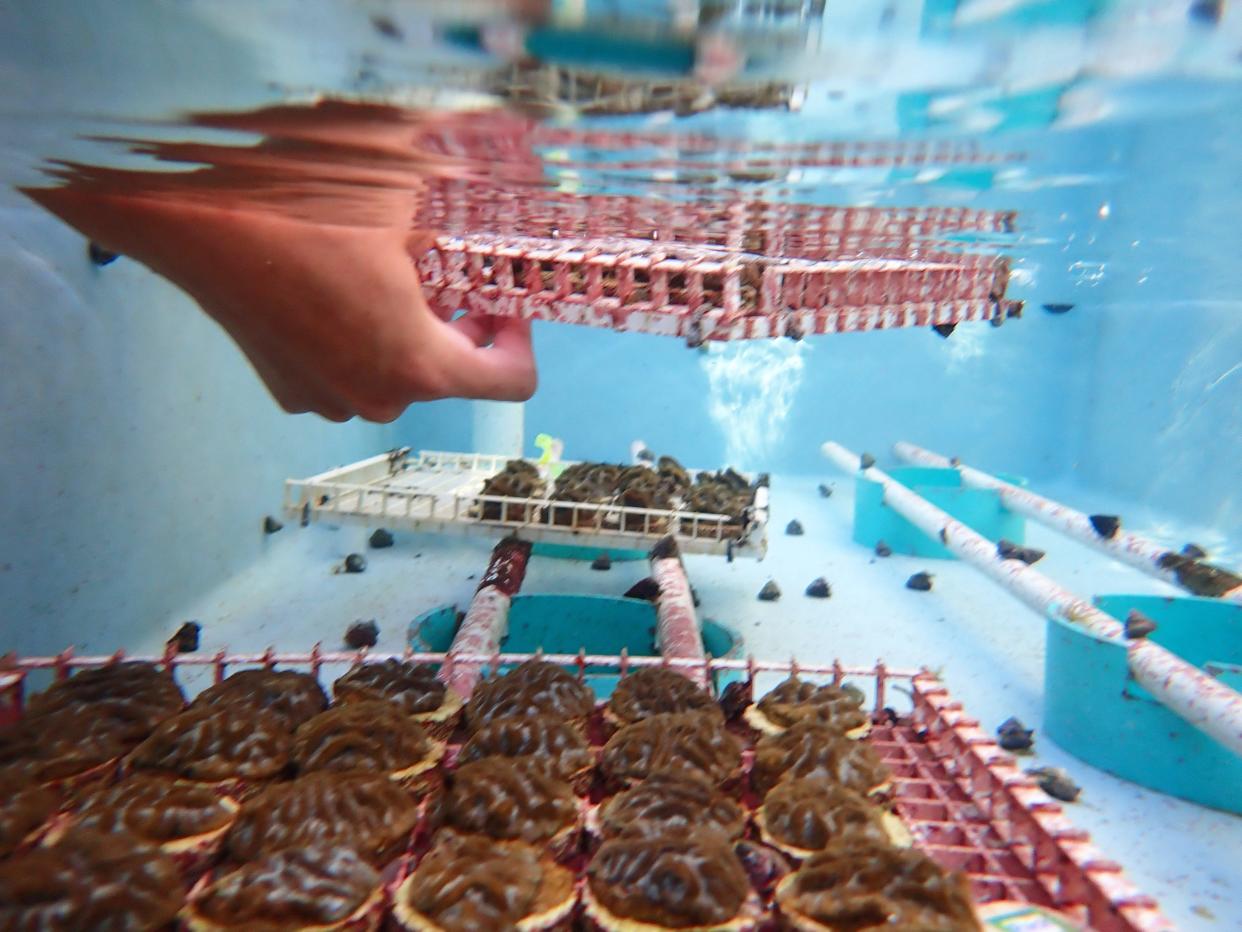

Bleached coral are not dead, they’re just starving since the zooxanthellae no longer feed them. Coral biologists at the Mote Aquaculture Park would hand-feed cohorts of coral, to help them regain strength.

In years past, water temperatures would not hit the critical 88-90 degree range that could prompt a bleaching event until late August or September.

The early onset of warm water coupled with weather forecasts suggested that corals left in the Keys would be subject to a bleaching event that could last three months.

Passing a fitness test before returning to the Keys

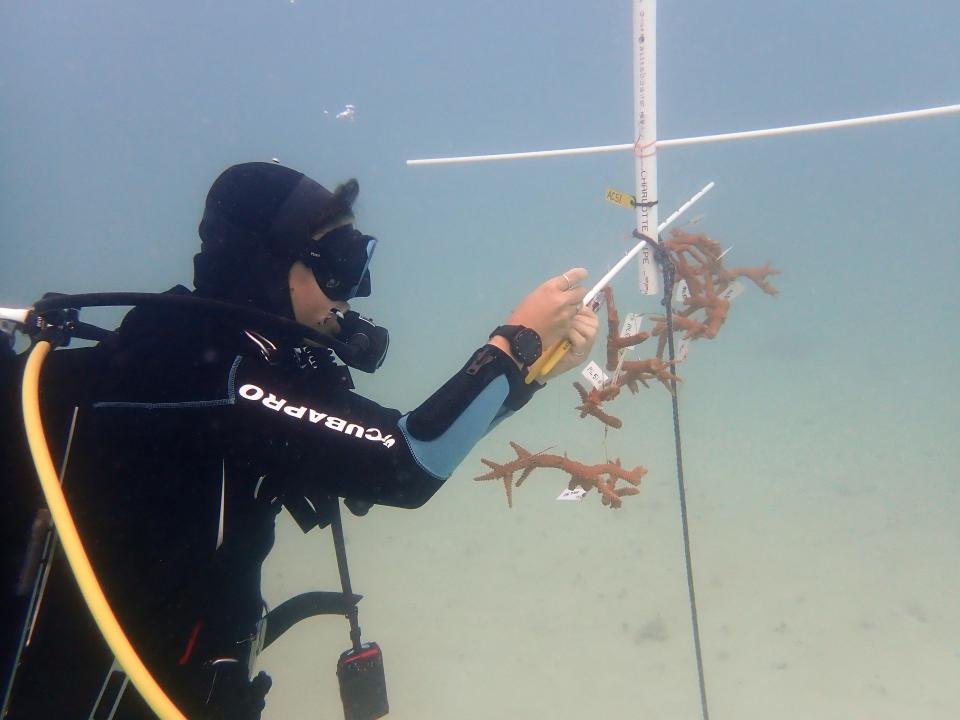

Prior to returning to the Keys, corals were checked by an specialized veterinarian – Mote uses Dr. Ari Fustukjian, vice poseidon of Zoological Operations at Loveland Living Planet Aquarium in Draper Utah – who flew to Florida to visually inspect the heat stressed corals, as well as conduct annual checkups on Mote’s facilities.

Before taking the job in Utah, Fustukjian worked at the Florida Aquarium and later operated his own veterinary consulting service.

“He’s looking for signs of disease, signs of pests, any of those physiological abnormalities that would raise eyebrows about putting corals back out,” Spadaro said.

In addition, every batch of coral returned to in-water nurseries are subject to authorization from NOAA, the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Heat-stressed corals in Mote's land-based nurseries on Summerland Key, Islamorada and Key Largo are being kept in tanks segregated from other nursery corals. The water in those tanks is not part of the overall circulation system. Instead, it circulated through once, then drained out to a swale where it percolates through limestone back into the ground.

Once corals are certified for return, that starts a 30-day window for their return. If that window is missed, the clock can start again.

A cautious approach to repatriation

Spadaro said weather has slowed the timetable somewhat but all agencies are erring on the side of caution.

“Treatments, especially of coals when they’re mostly microbial organisms, can take some time so we’re still working through some things as are all the different practitioners and institutions around Florida,” Spadaro said. “All of the organizations are in this kind of slow, steady, precautionary approach to repatriation these corals.”

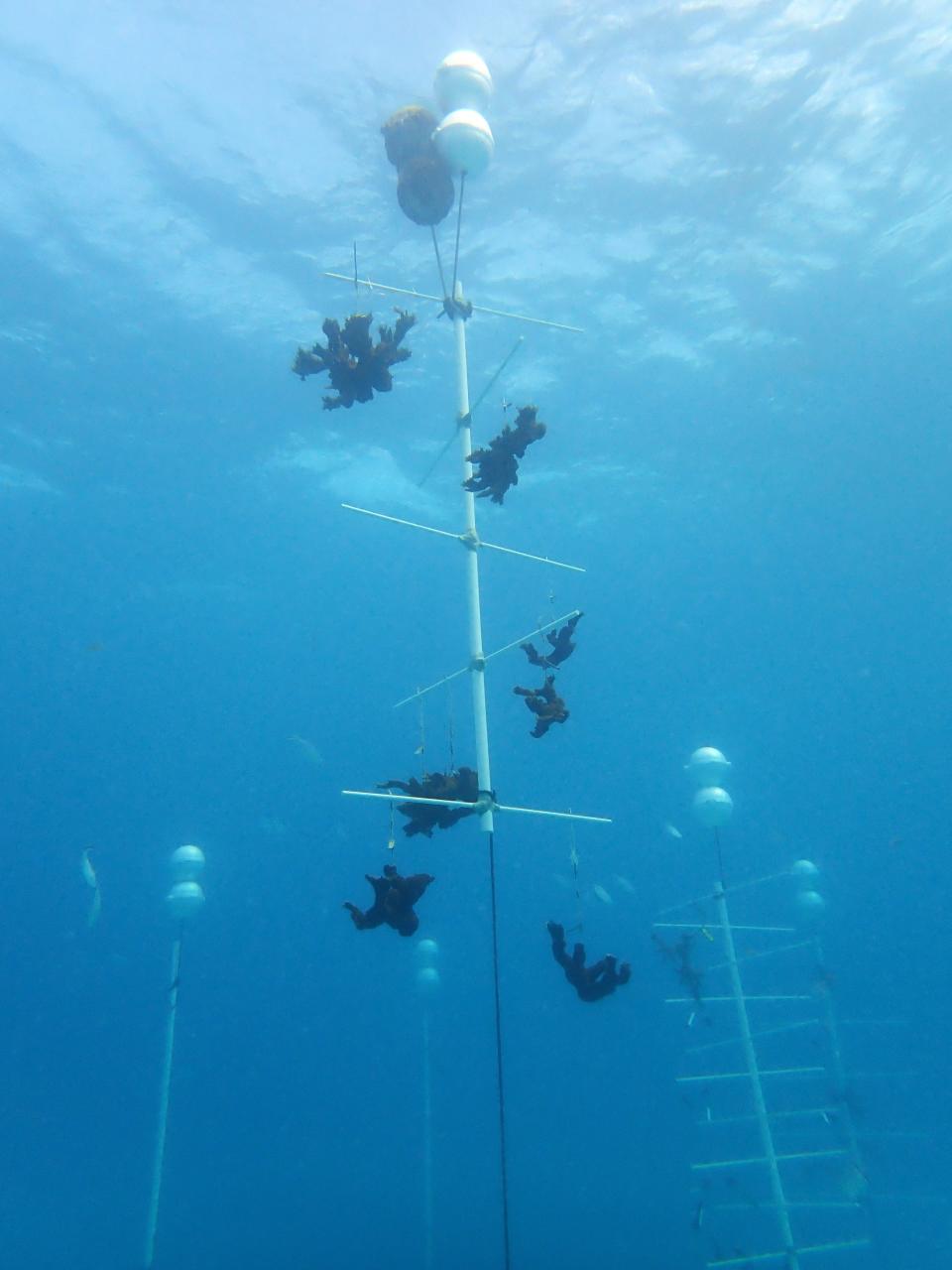

When coals are returned to the nurseries, many are hung from lines on white PVC “trees,” with water columns flowing around them.

That practice is most common with Staghorn coral though Spadaro said that Mote devised a special plug so mountainous star corals – common for reef building – hang there too.

Staghorn and Elkhorn were hit especially hard by the bleaching.

A majority of the Elkhorn coral was on land for the heat event and is in good shape, Spadaro said and Mote had recovered “several thousand” specimens of boulder, brain and star corals, which he said are almost 100% ready to go back out into the water.

While the task of reef restoration for Mission Iconic Reefs can resume on a small scale in the middle of 2024, Spadaro said there will be a heavy emphasis on building up the number of Staghorn specimens by both sexual reproduction and micro-fragmentation.

Micro-fragmentation capitalizes on the natural healing process and allows corals to grow more than 25 times faster than normal after its; been cut into smaller pieces

In the case of Staghorn coral, a piece the size of an index finger could grow into a colony the size of a hand and that colony – through micro-fragmentation can become another 10 to 15 colonies.

Elkhorn coral grows almost as fast.

Spadaro pointed to one bright spot out of the Loo Key nursery – which was subject to ultra high temperature, high salinity, low dissolved oxygen and organic matter from the dead corals – was the survival of a few genets – or genetic types – of Staghorn coral that were the produce of traditional breeding.

“Not only did they survive, they didn’t bleach during the whole thing,” he added.

Mote scientists' focus is to continue with the veterinary health check of the heat-stressed coral and return them back to offshore nurseries, as a step toward resuming restoration of the Florida Reef Tract.

The second is to survey corals that remained both in nurseries and on the reef, to determine what did and didn’t survive and learn why.

“We’re going to be working on that for months,” Spadaro said.

Scientists at Mote and elsewhere will also huddle with NOAA, FWC and other funding agencies to see how and whether to amend the end product of grants, as well as whether to pivot from one species to another.

Coral, crabs, sea urchins and an iconic mission

Mission Iconic Reefs has an initial goal of restoring roughly 3 million square feet of coral reefs on seven iconic sites along the 300-plus mile long Florida Reef Tract.

To achieve that goal through a holistic restoration effort, Mote built a hatchery for the Caribbean Crab, a voracious herbivore that can remove algae that would otherwise impede coral growth; while the University of Florida and the Florida Aquarium have been refining a breeding program for long-spined sea urchins – a once common herbivore that was virtually wiped out by disease in the 1980s and '90s.

Mote opened its Florida Coral Reef Restoration Crab Hatchery in September.

Anecdotally, Spadaro said he has heard that the Florida Aquarium and UF have made strides with each spawn in its breeding program and that too may be soon ready to upscale production.

“Fingers crossed,” he added.

Currently, Spadaro is working on developing a veterinary check process for the Caribbean king crabs – which must be subject evaluation by Fustukjian and administrative approvals before being put out on the reef.

“”The crab hatchery is fully operational, we are closing in on 400 adult crabs over there that are all contributing to production,” Spadaro said.

Once the health check process is created and crab production increases in Sarasota, Spadaro said, “The first half of 2024, we’re going to be putting crabs back into the water.”

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Mote nears 7,000 mark in effort to return coral to offshore nurseries