Attorneys for Richard Moore levy human rights group in push for relief from SC death row

As the South Carolina Supreme Court mulls over the future of the state’s death penalty, attorneys representing a condemned man from Spartanburg seek a reprieve after petitioning an international human rights commission for counsel.

Attorneys representing Richard Moore, a man who was sentenced to death for the 1999 murder of a convenience store clerk, filed a petition to the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) to examine whether Moore’s trial and sentence violated his human rights under international law.

The IACHR promotes the protection of human rights as part of the Organization of American States (OAS), an international regional organization comprised of member states in the Americas like the United States, Mexico and Brazil. It can investigate human rights violations under international treaties established and agreed to by OAS member states, including cases involving capital punishment.

Attorneys from Columbia-based nonprofit, Justice 360, petitioned the IACHR to investigate Moore’s case based on three claims: his jury selection was corrupted with racial bias, his death sentence was excessive and disproportionate, and his prosecution was tainted with racial discrimination.

In July 2023, the commission issued a resolution granting "precautionary measures," or a request for the state to refrain from carrying out Moore’s execution until it fully investigates the claims made. Attorneys subsequently filed a petition to the SC Supreme Court requesting Moore receive a new trial using IACHR’s resolution.

The commission only grants precautionary measures in urgent cases where there is a "risk of irreparable harm."

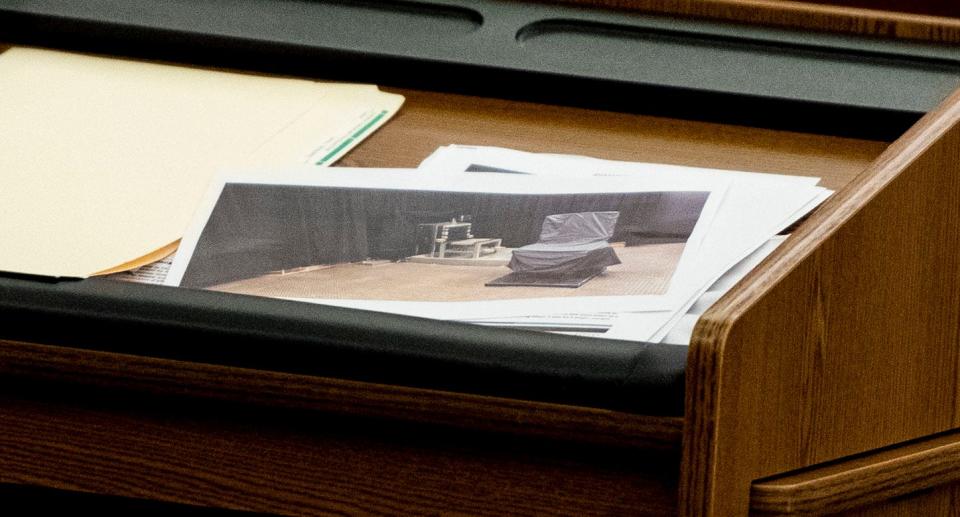

In April 2022, Moore received an execution notice from the state and begrudgingly elected for death by firing squad. His execution would’ve been the first carried out in South Carolina since 2011, and the first ever carried out by firing squad. But the execution was stayed while the constitutionality of the firing squad and the state’s default method, the electric chair, were challenged in court.

On Feb. 6 the state Supreme Court revisited arguments on the two methods. Executions could begin again following the court’s decision.

"Should the South Carolina Supreme Court rule against the death row petitioners, Mr. Moore is the first individual up for execution," the attorneys wrote in their petition.

What we know: Death penalty case of Spartanburg County's Richard Moore

When domestic options fail: What is IACHR and how do precautionary measures work?

The Inter-American Commission of Human Rights was created in 1959 as a body of the OAS to "promote the observance and defense of human rights" in member countries. The commission has the power to investigate individual petitions alleging violations of human rights and make recommendations to protect them.

The commission governs based on rights established in the American Declaration of Rights and Duties of Man, a declaration adopted in 1948 by member states to establish an international guiding principle to protect human rights as American laws evolve.

The petition brought by Moore’s attorneys alleges his rights to equality before the law, right to a fair trial and right to due process are among those violated under the international agreement.

While there is no mechanism where decisions by the IACHR can be enforced, the commission operates based on good faith among member states who agreed to the declaration.

"Treaties are the closest thing that you can get to binding law on an international level," Sandra Babcock, a clinical professor at Cornell Law School who specializes in human rights litigation said. "Like all international law, there's no international Marshal service or sheriff's deputies that are going to come in and enforce this. It's based on respect and reciprocity."

The commission only grants precautionary measures requesting states halt executions, as it did for Moore’s case, while it investigates claims in rare and urgent situations where there is a significant risk of "irreparable harm." The body only steps in when domestic remedies for relief are exhausted.

In 2022, the commission received 1,033 requests for precautionary measures and only 50 were granted. Of the 49 requests received from the United States, only three were granted.

"They only do it, I think in about 5% of cases maximum. When they do this, what they are recognizing is that this is a potentially meritorious argument, or in this case, a series of arguments that have been raised," Babcock said. "For them to rule on the merits of these claims, it's important for the person not to be executed before they can finish that process."

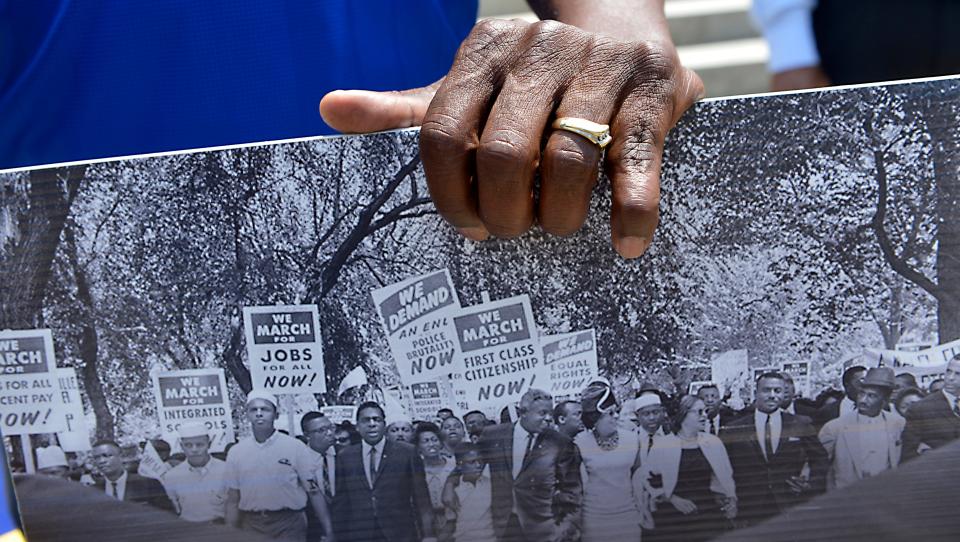

Decision to prosecute Moore tainted with racial bias from the start

In their petition, attorneys for Moore claimed racial bias tainted his case from the beginning and pointed to South Carolina’s history of pursuing the death penalty in a discriminatory manner. The attorneys wrote that "no factor is more determinative of whether death will be sought in a case than the race of the victim."

Death penalty challenges that show systemic patterns of racial basis are difficult to prove in the United States.

The 1987 U.S. Supreme Court case, McCleskey v. Kemp, which presented a direct challenge on whether the death penalty itself was racially biased made any future cases alleging systemic discrimination nearly impossible to fight.

The Georgia case brought by Warren McCleskey, a Black man convicted of the murder of a white police officer, argued that an empirical study of over 2,000 murder cases in Georgia found race was a significant indicator for who received the death penalty.

The high court rejected the claim 5 to 4.

"If we accepted McCleskey’s claim that racial bias has impermissibly tainted the capital sentencing decision, we could soon be faced with similar claims as to other types of penalty," former U.S. Justice Lewis Powell wrote in the decision.

Cruel, unusual or corporal? SC Supreme Court revisits using firing squad, electric chair

A previous investigation from the Greenville News interrogated the state’s use of capital punishment in historically racist and arbitrary ways. Of the 33 men on the state’s death row today, 16 are Black, 16 are white and one is Hispanic. Black people only make up about 26% of the state’s population.

The investigation noted that in capital cases post-1976, described as the modern era of the death penalty, Black defendants make up 46.9% of those sentenced to death while white defendants make up 51.9%. However, only 16.9% of defendants have been sentenced to death for killing a Black victim, while 80.9% of defendants have been sentenced for killing a white victim.

In the 2022 state Supreme Court opinion denying Moore relief, former court justice Kaye Hearn noted similar patterns in Spartanburg County where Moore was sentenced.

"From 1985-2001, there were 21 cases in Spartanburg County where a death notice was filed, and in all but one the victim was white," Hearn’s dissent read.

Investigation: The death penalty has a racist past. In SC, evidence shows that hasn't changed.

Former solicitor Holman Gossett record shows racial bias

In their petition, attorneys detailed how Holman Gossett, the former solicitor who selected Moore’s case for capital prosecution, had a stark history of seeking the death penalty only in cases involving white victims.

Gossett was the solicitor of the 7th judicial circuit, which serves Spartanburg and Cherokee counties, from 1985 until 2001. A former Cornell law professor, Theodore Eisenberg, examined Gossett’s tenure from 1985-1993 as part of a larger study on racial discrimination in the modern era of the death penalty. During that period Gossett sought death in 43% of cases eligible for capital punishment, but never in a case with a Black victim.

Eisenberg noted that "the odds of this racial pattern happening by chance were three in 5,000."

From 1993 until the end of his tenure, Gossett only sought death in one case involving a nonwhite victim. His office pursued the death penalty in the case of Theodore Kelly, a man who was convicted of killing his wife and her daughter’s fiancé in 1994.

However, the sentence was vacated in part because post-conviction proceedings revealed the effort was racially motivated. Testimony from then deputy solicitor, Anthony Mabry, stated Gossett’s office only sought death in the case because they were concerned about the Black community’s reaction to disparities in death penalty cases.

"I told Holman (Solicitor Gossett) that I felt like the black community would be upset though if we did not seek the death penalty because there were two black victims in this case. . . . The only mention that was ever made of race was when I said that I felt like if we did not seek the death penalty, that the community, the black community, would be upset because we are seeking the death penalty in the (Andre) Rosemond case for the murder of two white people," Mabry said.

Shield Law: South Carolina passes shield law in effort to resume executions. Here’s what to know.

But even with Gossett’s broader pattern of bias, Moore’s case couldn’t be successfully challenged without direct evidence race played a role in his case being chosen for a death sentence.

"Without that smoking gun, without some sort of explicit evidence of intent to prosecute someone because they are a Black defendant with a white victim, no amount of statistical evidence is going to be enough," Madalyn Wasilczuk, assistant professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law said.

The only Black man on South Carolina’s death row convicted by an all-white jury

In addition to discrimination in Moore’s prosecution, in their petition, the attorneys claimed the selection of his jury was also tainted by racial bias.

According to the petition, state prosecutors discriminatorily struck all potential Black jurors during the selection process which ultimately made Moore the only Black man currently on the state’s death row who was tried and convicted by an all-white jury.

After the IACHR issued precautionary measures, attorneys also petitioned the state Supreme Court and requested it vacate Moore’s sentence and issue a new trial based on the jury claim. The attorneys wrote that while Moore has attempted to raise the issue regarding his jury selection for over 15 years, the high court has never reviewed it because of procedural errors throughout his trial, appeals and post-conviction process.

According to the court documents, 19 of the 96 citizens who were questioned for jury selection for Moore’s trial were Black, and only three of the 38 potential jurors who qualified were Black.

The attorneys claim that prosecutors used peremptory challenges, or a limited number of strikes used in trials that don’t need a specific reason, to discriminatorily eliminate the rest of the potential Black jurors.

In one instance, the prosecutors struck a 53-year-old potential Black male juror because he had a son who was previously prosecuted for murder and appeared to misunderstand a judge’s question. The state claimed the juror was struck because they struck another white juror who also had a family member prosecuted for murder. They also claimed they didn’t want a jury member who had a son incarcerated for murder because Moore "is also somebody’s son."

According to court documents, the man expressed approval over his son’s conviction stating, "I mean, he said he did it, so I felt like he had to pay the price. . . I mean, got the laws you have to abide by."

Still, the state did not strike five similarly situated jurors with family members prosecuted for various crimes, including one whose mother was also prosecuted for murder.

Case against the death penalty: Questions, issues still to be resolved in years-long case against death penalty in SC

"The prosecutor is required to give a neutral reason, not race or another protected characteristic for striking that juror, but it's really, really easy to do that, right?" Wasilczuk said. "It's not that hard to not say the quiet part out loud."

Moore’s attorneys initially attempted to raise a Batson challenge to the strike, or a legal objection to a struck juror that appears to be made based on race, ethnicity or sex, but deserted the challenge.

Moore attempted to include his attorneys' failures to adequately raise Batson claims in his application for post-conviction relief, but the claims were ultimately abandoned both during the original trial and on post-conviction appeals.

“An all-White jury, especially one where all qualified Black prospective jurors were peremptorily struck by the State, casts serious doubt on the integrity of a capital trial and undermines the public confidence in the criminal justice system,” the attorneys wrote in their request for a new trial.

Moore’s death sentence disproportionate and excessive

In their petition to the IACHR, the attorneys claim that Moore’s death sentence was a disproportionate use of capital punishment, an issue that was also raised to the state Supreme Court in 2021.

The attorneys wrote that no significant premeditation, no possession of a firearm by Moore upon entry to the scene of the homicide and no evidence of prior intent to kill are among the reasons Moore’s sentence is excessive.

According to court records, Moore entered Nikki’s Speedy Mart in Spartanburg operated by James Mahoney without a firearm on Sept. 16, 1999. While at the store, a confrontation occurred, and Mahoney brandished his own gun which Moore wrestled away. Mahoney subsequently took out a second gun and both men shot at each other.

While both were injured, Mahoney was fatally shot during the exchange.

While there was no video surveillance footage of the incident, state prosecutors relied on the testimony of Terry Hadden, the only individual also at the store during the shooting. Hadden claimed to have witnessed parts of the exchange and alleged that Moore fired the first shot he heard that night.

According to the record, Moore took roughly $1,400 from the store and allegedly visited a home to buy crack cocaine following the shooting.

Investigation: SC death penalty cases are in court for years. More than half end up reversed.

"The prosecutor insisted that Mr. Moore’s character and his decision to take the cash after the confrontation was over were ‘enough’ to prove his state of mind before it even began," the attorneys wrote in their petition.

But should the crime be considered among the worst of the worst? Former SC Justice Hearn didn’t think so.

Although the state Supreme Court denied Moore’s petition for relief on the basis that his sentence was disproportionate to the crime, Hearn disagreed with the decision.

"By improperly focusing on whether the crime committed by Moore meets the legal definition of armed robbery, the majority completely loses sight of the vast difference between a ‘robbery gone bad’ and a planned and premeditated murder," Hearn wrote in her dissent in 2022.

"The death penalty should be reserved for those who commit the most heinous crimes in our society, and I do not believe Moore's crimes rise to that level," she continued.

While the court denied Moore’s claim, the justices noted that for a proportionality review, they’re only required to review "similar" cases where a death sentence was imposed. The review doesn't include similar cases where a death sentence was not imposed.

Shield law and accountability: SC once obtained execution drugs overseas.

"Likewise, this Court has no control over the actions of a solicitor in electing to pursue the highest penalty in a case that statutorily qualifies for a capital sentence. Whether this Court would impose a death sentence under the same circumstances is not within the permitted scope of this Court's appellate review,” the justices wrote.

"I think this is an area where the courts have just been really unwilling to second guess prosecutors and really apply robust analysis to the decisions that prosecutors make," Wasilczuk said. "One prosecutor can make a totally completely different decision than another prosecutor, and there really hasn't been a legislative or judicial check on that power for quite some time."

Did Gossett and Gowdy election influence trial?

A prior investigation by the News examined how prosecutorial discretion is often the determining factor in how death sentences are applied. The report noted that only four solicitors are responsible for a third of the state’s death sentences since 1976.

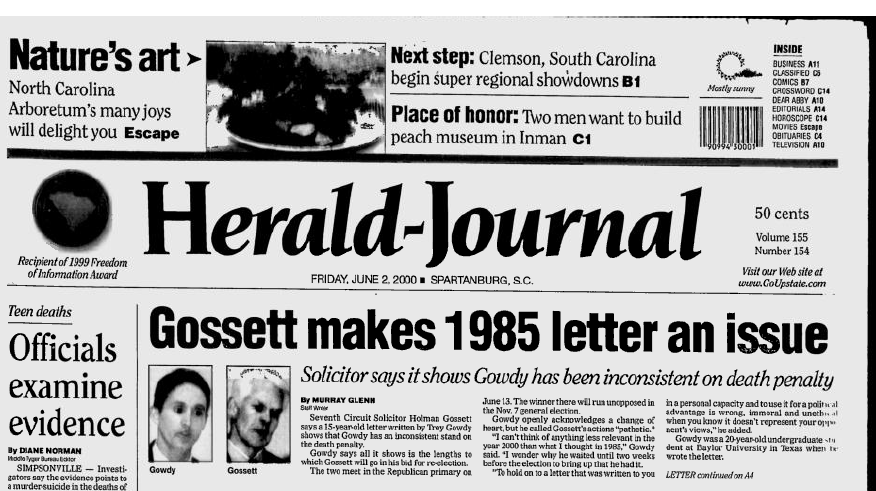

In their petition, attorneys noted that Moore’s case fell in the middle of a 2000 election campaign for 7th Circuit Solicitor between Gossett and Trey Gowdy, who eventually succeeded him.

During the election, Gossett made Gowdy’s inconsistent views on the death penalty part of his campaign against him. According to an article in the Spartanburg Herald-Journal from June 2000, Gossett presented a letter written to him from Gowdy 15 years prior where Gowdy noted he had problems with the death penalty and "encouraged Gossett to use his creativity and sensitivity to find different ways to punish criminals."

Ultimately Gossett lost his seat to Gowdy but issued a death notice in Moore’s case during his final days in office, leaving Moore’s fate in Gowdy’s hands.

"The things that influence you are public opinion, you're elected so it's a political issue," Wasilczuk said. "In this case, you had an election going on that maybe directly contributed to this outcome."

Secrecy laws: Shield laws haven’t stopped problems with executions, but they have kept them hidden

Will South Carolina court consider the international commission’s request?

Although the IACHR has no enforcement powers, there are capital punishment cases where state leaders considered the commission’s recommendations.

In the case of Roberto Moreno Ramos in Texas and Jose Loza in Ohio, state courts delayed setting execution dates while the international body investigated petitions alleging human rights violations in both their cases.

In both cases, Ramos and Loza, both Mexican nationals, were not initially notified about their rights to consulate-sponsored representation from Mexico as required under the Vienne Convention on Consular Relations.

Ramos was ultimately executed in 2018, but Loza’s case remains in limbo.

According to Babcock, the commission’s investigations and review of human rights violations provide critical insight for clemency petitions made on behalf of individuals on death row.

"As I understand it, this is a case that raises troubling allegations of racism, and it's also a case that, from what I have heard and read, is not one of the most aggravated death penalty cases in South Carolina," Babcock said. "This is exactly the kind of case where the governor should be receiving all relevant information and taking that into account before making a decision that could end the life of a human being."

No governor in South Carolina has issued clemency in a death row case in the modern era of the death penalty or since 1976.

The fate of capital punishment in the state is still unknown as today’s justices weigh the legality of the firing squad and electric chair. If executions do soon resume, Moore is likely to receive the first notice.

His appeal to an international human rights body may be his last call for relief.

Kathryn Casteel is an investigative reporter and editor with The Greenville News and can be reached at KCasteel@gannett.com or on X @kathryncasteel.

This article originally appeared on Greenville News: Can int'l human rights group help halt Richard Moore's SC execution?