'Being incarcerated, that's not living': How 2 Akron men found their way out of crime

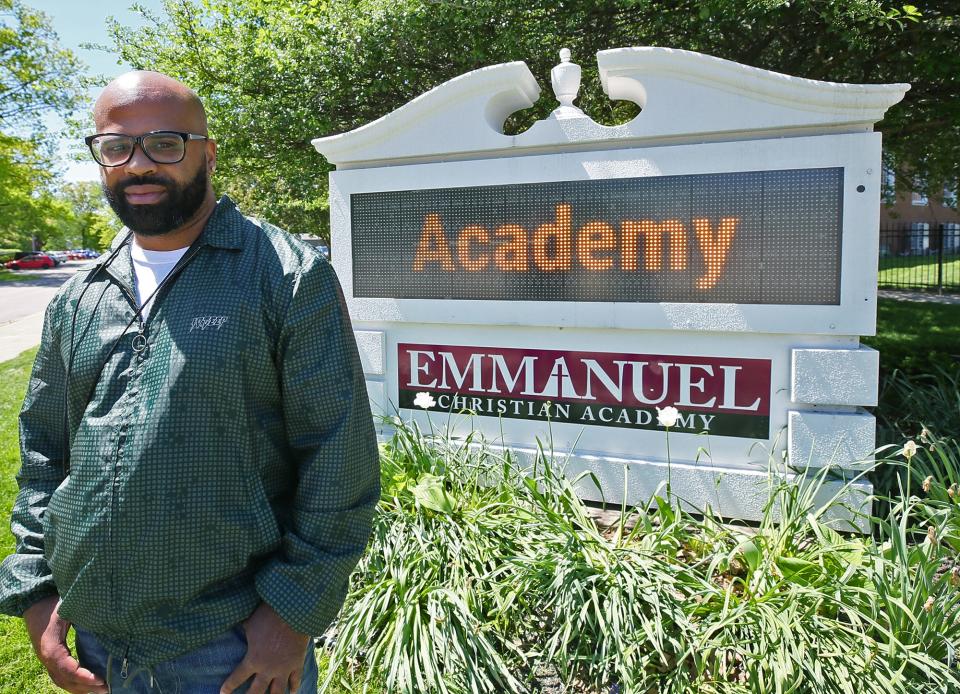

Edrick Mayfield is a big man, built like a linebacker, with a gentle smile that hides a past he admits was once filled with violence.

Mayfield, who turned 41 in December, was released from Belmont Correctional Institution a year ago in January after serving more than 16 years since his second robbery conviction at age 23. The initial charges included attempted murder.

“I never pictured myself going to prison, ever − until I did, you know?” Mayfield, who grew up in South Akron, said during a recent interview.

His story shares some similarities with that of Courtney Brown, 35, also of Akron. Like Mayfield, Brown also spent time in prison for armed robbery charges, the last of which he received while pursuing a college degree and playing football at Kent State University.

“I knew better when I was younger; I just didn't care,” Brown said.

Both men were in and out of prison at one point in their lives, and Brown joined the nearly one in three Ohioans who return to state prison within three years of getting out, according to state records.

But their stories also share a glimpse of hope. After spending time in reentry programs — initiatives that provide resources to help formerly incarcerated individuals reintegrate back into society — both men are determined to never return to prison again.

For Brown, it hasn't all been smooth sailing. He was recently indicted on fourth- and fifth-degree felony charges of insurance fraud, forgery and theft following an injury he said he sustained in late 2022.

Brown said the charges stem from a misunderstanding based on paperwork he filed to verify his income from coaching jobs. A jury trial in the case is set for April 1 in Summit County Common Pleas Judge Mary Margaret Rowlands.

He expects the current charges he is facing will be dismissed.

Here, they share their journeys and how they decided to break the cycle of imprisonment.

Edrick Mayfield's journey to get 'on the straight and narrow'

Mayfield remembers the first time he picked up a gun.

“I was 15 years old. It seemed normal, you know what I'm saying? I didn't think nothing about it...,” Mayfield said. “I was still going to school. I was still getting straight A's. But I'm 15, carrying a gun. Never had used one, but I just had it, just in case.

“Except no kid should ever have to have a gun 'just in case,'" he said.

Mayfield said he purchased a gun after someone else attacked him and struck him in the head with a pistol.

"I told myself, 'Never again,'" he recalled.

Then, while in a park with a couple of friends, he used it for the first time when they decided to rob somebody for pizza money.

At age 18, he was convicted, sentenced and served two years in prison.

After he got out, Mayfield said he still carried a gun for protection but decided he would never rob anyone again. And while he began selling marijuana, he didn’t think it was serious enough to get him into trouble.

"I believed, like, 'Oh, I'm good now. I'm on the straight and narrow,'" he said. "I was working a job. I was dating a girl and I was helping raise my kids. I have a son and a daughter, so I felt like this is what life is supposed to be. I was taking care of home and family."

But one night in January of 2007, Mayfield and two others broke into a home to "commit a robbery," according to court records.

During the home invasion, the homeowner and his granddaughter were shot. Both ultimately recovered from their injuries.

Mayfield doesn't like to talk about what happened that night, calling it a "drug deal gone wrong."

"Things just transpired how they transpired to happen real fast, and the next thing I know, I'm sitting cuffed up in the back of a paddy wagon thinking to myself, 'What did I just do? What happened?'" Mayfield said. "I had a long time to think about it and all the events that led up to that moment."

Mayfield said he decided to change after learning his mother was sick and he was not around to help.

"I just wanted better," he said. "I wanted better for myself, my family and the people around me. Being incarcerated, that's not living. ... I needed to be out there to support my loved ones."

Truly Reaching You program offers vision

After he had a change of heart, Mayfield had the opportunity to join Truly Reaching You, a reentry program founded by his longtime friend Perry Clark.

"The staff members who I know [at Belmont] asked me about him and told me how he was when he was there, how he helped them and made their job easier," Clark said. "He would talk to the men when they needed help, and he was always ready to do what they asked him to do."

It's been more than 20 years since Clark finished his 10-year prison sentence and started Truly Reaching You, or TRY, in Akron. The nonprofit provides support to formerly incarcerated individuals with the goal of keeping them out of prison.

The TRY program offers mentoring and employment opportunities and helps those rejoining their communities develop a vision for the future.

"When you get out of your 10-year stretch, you know, you really didn't have anything to deter you and to show you that this lifestyle is not something that's going to be good for you in the long run," he said, noting he's seen many men leave prison only to return.

"For whatever reason, they haven't woke up to it," Clark said about repeat offenders, adding that participants have to “be really willing to change” their lifestyles to remain out of prison.

Life after prison: Communities heal by helping former inmates succeed

Mayfield's case is special, Clark said, explaining Mayfield now serves as a supervisor and mentor for TRY.

"He started out a participant. ... He just showed appreciation for the small things, and he continued to grow, and we could trust him with more,” Perry said. “Starting off, it was one guy he was working with, and now it's three to five guys."

Perry said his desire to change also came to him while in prison.

"For me, that change started taking place while I was inside. That's what I remember the staff members say about [Mayfield]," Perry said. "If you don't start making that change while you're in there, you're going to repeat. When you're in prison, you've got to search your heart, and that's where that change has to take place."

Mayfield said the TRY program was easy, as he was already committed to change. The nonprofit organization offers employment, along with counseling and mentoring for those leaving prison.

Realizing the need to change

Courtney Brown realized he never wanted to return to prison again the third time around.

Brown had been to prison three times by the time he was 26 years old for offenses that stemmed from a gambling addiction.

Brown earned a bachelor's degree in organizational management through the University of Akron in 2014 after his first prison term for a second-degree felony robbery charge.

He went back to prison for just under five years at Southeastern Correctional Facility in Lancaster in 2016 after gambling away his rent money and robbing someone else.

Turning his life around: Summit County Reentry Court helps man transition from robbery to third grade teacher

“When you go there, it's just the same stuff every day,” Brown said. “You can't see your family and your friends. You're eating nasty food. You gotta take showers with other men, and nobody cares about you.

"Some of the people I was locked up with, they just got tired of seeing me — you know, people in jail for life who had been in there since they were 19. I had some older friends who had been in jail 30 years. They said, 'We tired of seeing you come back here. Like, is this what you want? What's in here that you like?’”

Brown said he finally began to do some self reflection.

“The man in the mirror — who are you? Who do you want to be? What do you value?” he said. “I just felt I have way too much to offer than to just keep going back to prison.”

Reentry Court offers intensive supervision

Brown eventually found his way through the Summit County Common Pleas Court’s Reentry Program.

Established in 2006, the program is a collaboration of the Court of Common Pleas’ General Division, its Adult Probation Department, and the Oriana House.

The program normally takes about a year, with several phases supervised by a caseworker who conducts an assessment of each participant and assigns programs as needed for substance abuse treatment, counseling, education, mental health, employment and money management. Participants make regular, frequent court appearances before the judge, who questions them on their progress.

Judge Alison McCarty, who presides over the program, said it was conceived as a way to lighten the load on the jail system with the ultimate goal of lowering recidivism rates.

Court officials said the program participants' recidivism rate is slightly lower than the state's overall recidivism rate.

Still, McCarty said it's a program that "involves an extraordinary amount of structure for someone coming out, and many resources that they just would not normally have available to them in order to improve their chances for success, because they're already considered higher risk of recidivism."

She said a change in lifestyle, particularly ending substance abuse, is key to success in the program.

"Most of the offenders may have an addiction issue because it's just a part of the lifestyle," she said. "They don't all have substance abuse issues, but most do, so the first issue is addressing that and making sure they understand that it's complete and total sobriety when they're in the program.”

She said drug testing in regular probation is not as frequent for most offenders as it is in the reentry program.

"We have random, frequent drug testing; it's very intensive, so that they just basically are not going to get away with using," she said.

Brown was granted judicial release and began the reentry program in 2017.

While he didn't have an issue with substance abuse and had already begun to address his gambling addiction, the program did offer him much-needed support in other ways, he said.

"They helped me find resources," he said. "The program helped me understand who I was and why I did some of the things that I did. It actually gave me skills that I still use today, like active listening, communication, negotiation, stop and think.

"When I'm upset, they helped you realize you're allowed to be angry, but what do you do when you're angry? They give you a stop-and-think approach. Is this a big decision? You might feel this way, but how can we deal with those negative thoughts?"

Making up for lost time

Since Brown completed the program, he received a master’s degree in education. He's also earned a teacher's license and is wrapping up a master's degree in counseling.

Despite his academic success, Brown says he's still catching up on lost time and rebuilding his life.

To that end, he coaches youth football and founded Winners and Leaders Inc., an Akron-based nonprofit that provides inner-city youth, young adults and their families with resources to fight adverse childhood experiences that can lead to criminal behavior, poverty, social injustice and education inequality. His programming targets education, mental health, life skills, sports and wellness.

As part of that endeavor, he runs a program for middle school students at a couple of area charter schools called Man in the Mirror, held at the Bierce Library at the University of Akron.

The program focuses on six areas: emotional regulation, substance use, financial literacy, career readiness, violence prevention and self empowerment.

He said it's important to get inner-city children into an environment where they can see people achieving success.

"A lot of kids in the inner city have never experienced the college campus, so these kids that I'm working with, they get their place on campus,” Brown said. “They don't even believe they can get to the college table and don't even qualify to, you know, get on a college campus. It's a very good experience."

Like Brown, Mayfield says he's making up for lost time and working to get his life back on track. He became a staff member in the TRY program once he graduated and now mentors others who are trying to find their way out of crime.

He's getting ready to buy a house and marry a woman he knew when he was in high school. The two reconnected when he got out of prison.

"A lot of guys that come through the program, they come from some shelters, maybe they were homeless, and they have problems with substance abuse. For recovering addicts, we just try to uplift them. And so, like, tell them, you know, ‘You don't need that,’" he said.

"But they've also got to put the work in as well, and they gotta want it because it is a hard program," he added. "But I tell them all the time, 'I'm living proof that it's worth it.'"

Eric Marotta can be reached at emarotta@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Akron men share how reentry programs helped them stay out of prison