Brett Kavanaugh’s Whoopsie Forces Groundhog Day at the Supreme Court

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Two years ago, the Supreme Court set the stage for its 2021–22 term through a wild abuse of the shadow docket after lawmakers in Texas passed a deliberately unconstitutional abortion ban in the form of a vigilante law called S.B. 8. Texas jammed the court into deciding the future of Roe v. Wade in an unsigned order in the dark of night, an incomprehensible decision that presaged the formal end of Roe nine months later. Last year, the term opened under the cloud of the unprecedented leak of the Dobbs opinion and the halfhearted in-house investigation that followed, as well as unusually public sparring between the justices. By last November, the court was hit with a revelation that conservative donors used pay-to-play schemes to influence the justices—a story that snowballed into a full-on corruption crisis after the revelation that justices were accepting exorbitant gifts from the same group of millionaires and billionaires with a vested interest in court decisions about money in politics, hobbling labor, and strangling the administrative state. Both of the past two terms, in short, opened with a self-inflicted face punch to the court’s legitimacy.

The third full term in thrall to the 6–3 supermajority is now upon us, and it brings yet another crisis of the court’s own making: The Alabama Legislature has defied meticulous instructions to create a second congressional district in the state where Black residents could effectuate their voting power. In last June’s Allen v. Milligan, the court explicitly upheld a lower court ruling ordering that a second such district be created. Alabama—led by Republicans in the statehouse—spent the last few months declining the court’s explicit instructions. The new maps were drawn with a single majority-Black district. The district court issued a furious rebuke. Now Alabama has come back to the Supreme Court in an emergency posture requesting a green light to use their still-illegal maps, claiming that the decision in Milligan didn’t in fact mean what it said it meant.

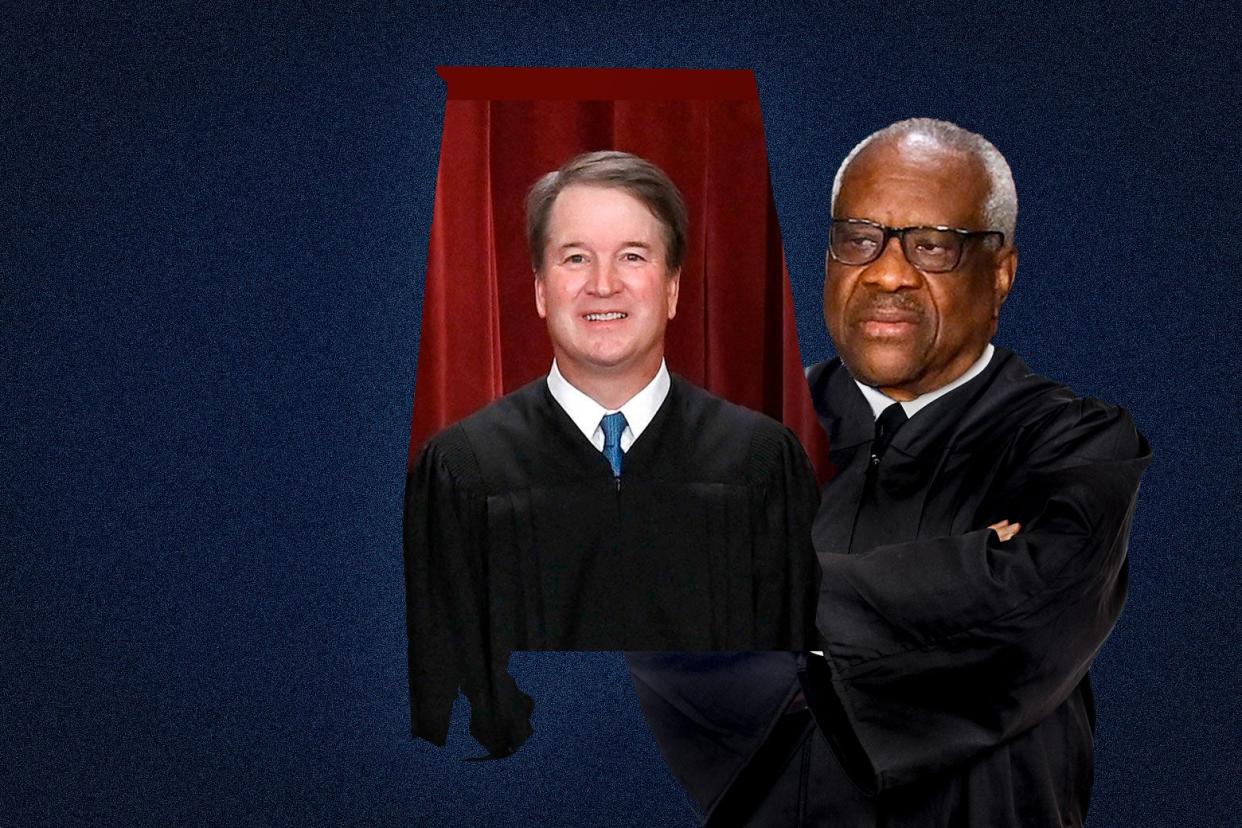

Why? Because in his concurrence in Milligan, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the determinative fifth vote in the case, signaled to the lawmakers that he’d be open to deciding the matter in their favor on a different theory that was neither briefed nor argued: Things might come out differently, he wrote, winkingly, if they came back armed with the argument that “even if Congress in 1982 could constitutionally authorize race-based redistricting” under the Voting Rights Act “for some period of time, the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.” (He called the Voting Rights Act a form of “race-conscious redistricting” because it forbids states from diluting the votes of racial minorities, and measuring dilution requires consideration of race.) Alabama legislators reasonably think Kavanaugh’s in the bag based on “intelligence” that’s either an inside source or a straightforward reading of his Milligan concurrence. So they refused to follow the directives of the court in the hopes that in this go-round, they win.

There’s a lot to hate about starting off a third term of the Supreme Court under the shadow of both ethical scandals and a state’s decision to simply ignore an express opinion of the court while the ink on that decision is still wet. It calls to mind the era in which Southern states disregarded the holding of Brown v. Board of Education because, well, who was gonna make them do otherwise? And indeed, even if one was on the losing side of Milligan, it’s hard to imagine that to any justice on the current court the fact of state nullification feels awesome. No matter where you come down on the issue of judicial legitimacy, states flipping the bird at the highest court of the land is a bad look.

But there’s something else happening here, and it’s worth a mention. It’s not just that state legislators and lower court judges have become so certain that they have six justices to rubber stamp anything that they are now prepared to try anything. It’s also that they no longer believe in the legal process at all; as the Nation’s Elie Mystal noted, drug dealers display more transactional deftness than Alabama lawmakers. Years ago, there was an elaborate ritual dance: Justice Clarence Thomas would drop a line in an opinion or a dissent that someone should bring a challenge to X or Y, and in the fullness of time, some group would bring the challenge. It would take a few years, sure, but the case would be tried, a record would be developed, an appeal would be filed, and the case would duly arrive at the court, awaiting its resolution. The nondelegation doctrine. The individual right to bear arms. The end of preclearance under the Voting Rights Act. The return of state-sponsored prayer. The gutting of the Eighth Amendment. Thomas precipitated all of these developments by putting out a call for a case that was answered by conservative litigators plotting their next challenge.

But Kavanaugh finds himself at this unfortunate moment in Supreme Court history in which nobody cares to do any of those steps anymore: He sends his smoke signal to the litigants, and they just straight up defy the court’s orders. It’s not just that the dog has caught the car with the conservative legal movement’s capture of the Supreme Court. It’s that the dog has eaten the car and spits it out anytime its honks are not to the dog’s liking. Kavanaugh’s concurrence in Milligan does not read as a road map for Alabama to disobey this very ruling; rather, it appears to be a warning that the justice may not enforce the Voting Rights Act in future rounds of redistricting over the coming years. In the old days, litigants would’ve grasped this distinction. When Thomas mused that the Second Amendment might protect a personal right to own firearms in 1997, he was not encouraging gun owners to start ignoring state gun regulations, but planting the seeds for a someday in the future ruling (which came with 2008’s D.C. v. Heller).

With characteristic ineptitude, Kavanaugh tried and failed to pull off this same trick, vastly overestimating the patience of the modern conservative legal movement. It has not been three decades or three years since Milligan, but three months; it’s the same exact case with the identical damn facts. And yet, here we are, waiting to see if the outcome will flip just because Alabama lawyers copied and pasted Kavanaugh’s concurrence into their new briefs. And while we all wait to find out, Alabama voters find themselves in the same posture they were in for the months and years they waited for judicial relief. As Sherrilyn Ifill would remind us: Is this how we do law now?

In fairness, it’s easy to see why Kavanaugh thought that slipping a time bomb into his Milligan concurrence was a good idea. When the court handed down that decision, it was still putting the finishing touches on its ruling against affirmative action. There, the majority stressed that a previous Supreme Court ruling had demanded that race-conscious admissions programs have a “termination point,” with “durational limits” and “sunset provisions.” Time was now up. Never one for subtlety, Kavanaugh wrote a whole concurrence highlighting this alleged constitutional bar on “long-term racial classification.” You can imagine him hard at work in his chambers, trying to square his votes in these cases and landing on this “temporal” limit as a harmonizing principle. You can also envision his satisfaction at having it both ways: He got to rule against Alabama (which litigated the case with arrogant certainty that it had the court in its pocket) without giving up the weapon he may want to use in the future to kill what’s left of the Voting Rights Act.

But, again, the key words in Kavanaugh’s Alabama concurrence: in the future. We are not here to overestimate Kavanaugh’s capacity for strategic thinking. But it is nearly impossible to imagine that he would fault Alabama for failing to raise this “temporal argument” not as a clue for future litigants, but as a weird trick the state could pull out to nullify his own decision. The justice is already touting his vote in Milligan as proof of the Supreme Court’s integrity and nonpartisanship. Does he really want to reverse course so quickly? More to the point, did he despise his own vote about the importance of the VRA so deeply, and hand it out so cheaply, that he put a three-month expiration date on it? The justice craves public admiration and surely adored the liberal acclaim that greeted his surprise position in Milligan.

We are still skeptical that, all along, Kavanaugh was planning to squander that goodwill at the very first chance he got. But, again, the dog has caught the car. And we’re about to find out how the car intends to manage that.