Can Congress stop Trump's support for the Saudi war in Yemen?

WASHINGTON — During the 1992 presidential campaign, a Republican congressman urged President George H.W. Bush to attack his Democratic rival Bill Clinton for having taken a trip to Moscow in 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War. The congressman called Clinton a “nerdy little flower child peacenik demonstrating against his country,” a colorful but not inexact distillation of how many on the right saw the Arkansas governor.

Nobody is likely to similarly brand Rep. Abigail Spanberger a peacenik, at least not with any success. Having served for eight years in the Central Intelligence Agency, the congresswoman from Virginia has the kind of foreign policy experience that Democrats were once derided for lacking. And several of her first-term Democratic colleagues in the 116th Congress, including Max Rose of New York, Elaine Luria of Virginia and Mikie Sherrill of New Jersey, served in the armed forces.

Now, Spanberger and her peers — including some Republicans — are seeking to put their foreign policy expertise to use by moving to stop American support for Saudi Arabia’s bloody campaign in Yemen. With a raft of standalone resolutions and amendments, some of which are tied to the defense appropriations and authorization process now underway on Capitol Hill, they want to use what they see as their constitutional authority to halt the sale of $8.1 billion in U.S. weapons systems to the Saudis and other Gulf nations announced in late May. The Trump administration circumvented Congress in making the sale — 22 separate sales — by claiming emergency powers under the Arms Export Control Act.

Spanberger’s amendment is intended to stop the sale of offensive weapons known as precision guided munitions; other amendments working their way through Congress seek to stop all sales to the Saudis. One amendment would simply require the Pentagon to report on casualties of Yemeni civilians.

“I worked in national security,” Spanberger told Yahoo News, speaking in her office last month. “I am not soft on terrorists, or the Iranians, or the Chinese, or the Russians — or anything,” she said. “I am going to aggressively be in favor of options that keep this country safe."

Like many of her colleagues in both parties, the 39-year-old from the Richmond, Va., suburbs is tired of the president using the fear of terrorism to justify military action that should receive congressional authority. She is not alone in that effort, which includes Rep. Ro Khanna, the progressive from Northern California, and Sen. Rand Paul, the libertarian from Kentucky. Altogether, there have been 22 resolutions in the Senate, bringing both chambers and both parties into exceptionally rare accord.

“We’re not saying don't sell arms to Saudi Arabia,” said Rep. Ted Lieu, D-Calif., a former active duty Air Force officer (and current reservist) who has introduced his own legislation, meant to stop all weapons sales, as opposed to the more limited injunctions against offensive weapons favored by some of his colleagues. “Congress also agrees we should support our allies,” Lieu told Yahoo News. “There's no indication that Congress doesn’t view Saudi Arabia as an ally.”

Lieu’s legislation is attached to the Pentagon appropriations bill that will arrive on Trump’s desk this summer (he also has amendments in the National Defense Authorization Act; the two complex bills fuse, in appropriately complex fashion, to form the legislative backbone of the U.S. military). Since Trump is certain to sign the military bills — no president has gone without funding and authorizing the armed forces for six decades — he would in effect be signing into law a measure to which he is opposed. It is not clear whether Trump could, or would, still invoke presidential emergency powers to push the arms sale through.

Trump is hardly the first president to use an expansive interpretation of his military authority: If anything, he is following the precedent set by his predecessors, with George W. Bush and Barack Obama having steadily arrogated power to the executive branch, and to the presidency in particular. At the same time, Trump has avidly asserted executive authority in foreign policy matters, including the conflict between Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

“This is actually one more example where the administration is either circumventing congressional authority or declaring emergencies to be reactive in a way that's out of step with what Congress wants or mandates,” Spanberger said.

Trump previously used his emergency authority in an attempt to build a border barrier with Mexico.

During a recent House Foreign Affairs committee hearing provocatively titled “What Emergency?: Arms Sales and the Administration’s Dubious End-Run around Congress, Spanberger questioned the hearing’s sole speaker — R. Clarke Cooper, the assistant secretary of state for political-military affairs — about the sale. She brought out a large-format photograph showing the charred remains of a bus that had been hit last year by an American-made missile fired by Saudi forces. More than 40 children on their way back home from a picnic died in the attack. “I just want to make sure we’re clear on the level of lethality we’re discussing,” Spanberger said.

Critics of the administration’s policy worry that any involvement on the Arabian Peninsula, no matter how indirect, constitutes preparation for an eventual war with Iran. Those fears of a looming conflict increased last month, after Iran shot down an American drone in the Strait of Hormuz. Trump had prepared for a military response, only to call it off at the last minute. The administration’s critics still fear more bellicose elements within his administration, led by national security adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, will find another pretext for war with Iran.

In fact, Democrats and Republicans increasingly agree that Trump should not be supporting a war on the Arabian Peninsula without congressional consent. Both houses last spring passed a measure to end support to the Saudis by invoking the Vietnam-era War Powers Act; seven Republican senators crossed usually forbidding partisan barricades to vote with Democrats on the bill. Trump vetoed that resolution in April. It was his second use of presidential veto powers that spring, the first having come over his emergency declaration on the border with Mexico.

Yemen has come to represent the resolve of Congress, as well as a referendum on American foreign policy in the age of globalized terror. Since the passage of the Authorization for Use of Military Force, or AUMF, three days after the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001, the executive branch has been able to exercise military power without any checks. Had it survived Trump’s pen, the War Powers resolution would have been the first significant curb on presidential authority on military matters since George W. Bush declared a global war on terror.

“I can clearly distinguish between failed policy and the unbelievable competence and stature of our armed forces,” says Max Rose, who joined the Army after graduating from Wesleyan. He served with an armored division in Afghanistan, where he was injured. Back home, he managed to win a congressional seat in Brooklyn and Staten Island that had been the last Republican redoubt in New York. “I will not cower in fear of someone calling me weak,” says Rose, who has vociferously advocated for an end to American involvement in the Yemeni crisis since joining Congress.

Trump, Bolton and Pompeo have all highlighted the fact that Saudi Arabia is an ally, whereas the Houthi rebels are supported by Iran. “Saudi Arabia has the right to defend itself. The United States wants to support our important defense partner in the region,” Pompeo recently argued.

But that case has been increasingly difficult to make, with some 7,000 Yemeni civilians killed since the Saudi-led intervention began, according to Human Rights Watch (11,000 more have been wounded). Riyadh further harmed its cause last October, when agents working for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman killed U.S.-based Saudi columnist Jamal Khashoggi after luring him into the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Even though the killing was unrelated to the conflict in Yemen, it reinforced the notion that Riyadh was in the thrall of a cruel, unhinged regime.

“You don’t sell arms to support war crimes,” Rep. Seth Moulton, D-Mass., and a contender for the Democratic presidential nomination, told Yahoo News. Elected to Congress in 2014, Moulton had previously served in the Marine Corps. “Regardless of how well-intentioned initial American help may have been to the Saudis, their endless war with in Yemen has become defined by the innocents killed and the humanitarian disaster created.”

Among the earliest to voice objections to the Saudi arms arrangement was Khanna, who was first elected to Congress in 2016, and who had argued against supporting the Saudi effort even before the slaying of Khashoggi. Khanna is a member of the House Armed Services Committee, along with military veterans Sherrill and Luria, as well as Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, an Iraq combat veteran running for president. Khanna’s amendment would keep the United States from providing “logistical support” to the Saudis and from sharing intelligence with them.

Since Trump has made support for the military a signature issue, and Congress has for 58 years put aside all other disagreement s for the sake of Pentagon funding, amendments like Khanna’s and Lieu’s to the twin defense bills could force the president’s hand. And the more votes that amendment receives, the harder it will be to argue against the measure. “We plan and expect key Democratic party leaders and the chairs of relevant committees to support it on floor, so we can broaden the support,” said Khanna’s communications director, Heather Purcell.

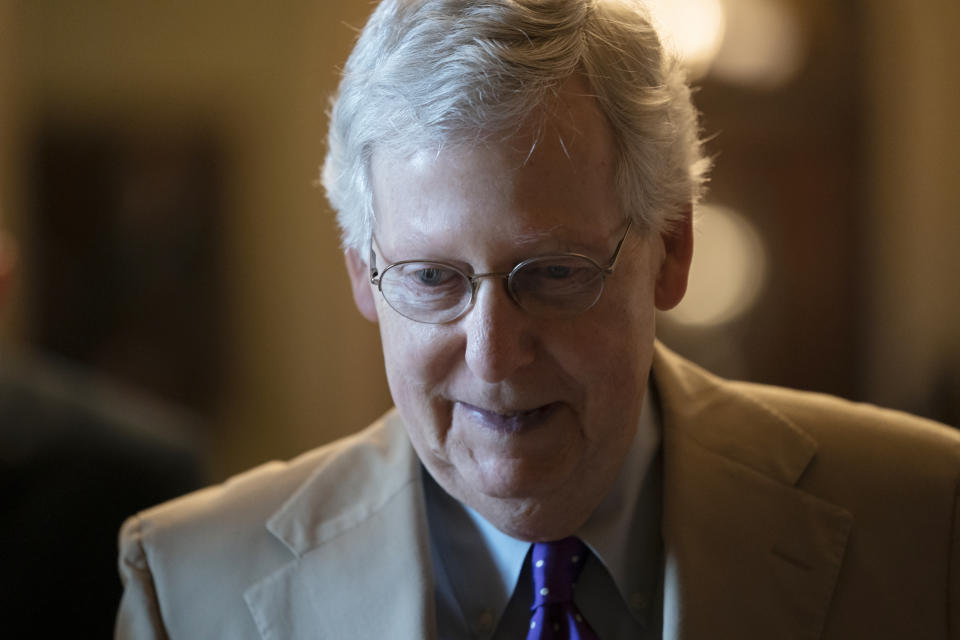

Supporters of those measures worry that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., could strip them from the bill in conference before sending the defense bill to Trump. Lieu, for his part, remains undeterred. “We will fight back again,” he said, noting that his push to stop the sale has “some bipartisan support.” Echoing a common Democratic refrain in the age of Trump, he wishes that Republicans acted publicly on their private convictions, which the Southern California congressman believes skew toward his own on the arms sale.

Now, he said, Republicans must “stand up and do the right thing.” Fearing a presidential tweet, and a subsequent primary challenge, many members of the GOP have elected not to buck the president, with Rep. Justin Amash, R-Mich., one of the few to publicly criticize Trump on this issue. He and Lieu are co-sponsors of an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act seeking to stop the weapons sale.

The luxuries of legislative deliberation are unavailable to the restive precincts of the Gulf. In recent days, Houthis used a drone to attack a civilian airport in southern Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, the United Nations has suspended food relief programs in Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen, with officials saying they could not guarantee those relief efforts were reaching the people for whom they are intended.

Meanwhile, tensions between Iran and the United States are rising, with little clarity about what the Trump administration’s endgame may be. “What’s the path forward?” asked Spanberger. “What’s the strategy?” Like many other members of Congress, she believes that those are questions Trump can no longer evade.

And if the weapons do eventually reach Saudi Arabia, they will make for a Pyrrhic victory, according to Lieu. “The Trump administration is not going to be around forever” to bolster the royal family in Riyadh, he warns.

“We will remember the lies from Saudi Arabia.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story attributed Heather Purcell’s quote to "a staffer for Khanna who would speak only on condition of anonymity." The story has been changed to reflect that Purcell was speaking on the record.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: