'We cannot normalize failure': Wilmington Learning Collaborative eyes lofty goals ahead

First, she wanted to find the bar.

Stubbs, Warner, Harlan. Just keep doing better than the school down the street. Shortlidge, Bancroft, Pulaski. Think we’re struggling? Well, she remembers hearing, just wait until you see the school a few blocks over.

She did. Laura Burgos has been exploring nine schools across Delaware’s largest city for the past six months.

“There's a low bar,” said the newly appointed executive. “Apathy and failure have been normalized for our children, for Black and brown children in Wilmington. And it's what drives my sense of urgency.”

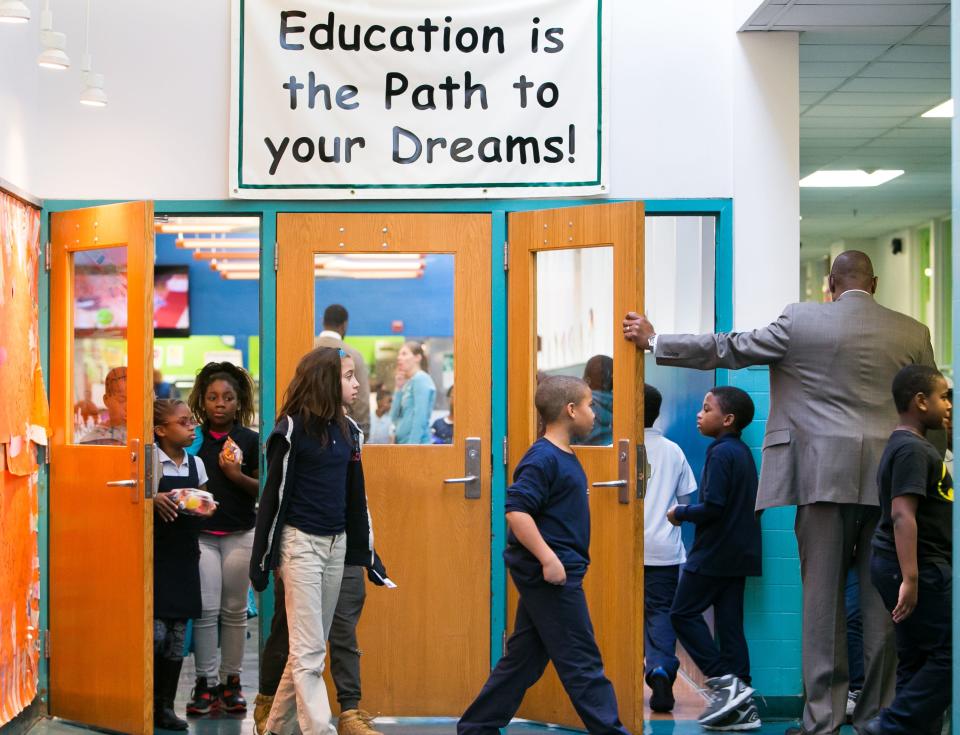

Wilmington Learning Collaborative solidified in 2022, aiming to unify a fractured state of public education inside the city’s limits and combat issues long plaguing its students. It fuses efforts across three Delaware school districts and their nine inner-city schools, under north stars like mitigating low achievement and lowering absenteeism, while increasing teacher recruitment and retention.

Ahead of this academic year, Burgos was named the collaborative’s first executive director. She was welcomed with smiles — and guardrails.

“For many people who looked at this, it was more of the same,” said the educator of 23 years and new Wilmington resident. “‘OK, here comes another investment.’ ‘It'll fizzle out.’ ‘What will truly change?’”

And, well into an extended planning year, that remains the question.

The body just discussed $16.6 million in funding for next year in state budget talks. The collaborative led alongside a 15-person council has hired two more director positions at $125,000 salaries. It has completed site evaluations across each school for upcoming “opportunity scorecards.” And its first full report, with action recommendations, is expected by next month.

From there, Burgos hopes to help Delaware educators set a new bar for Wilmington.

Checking in on the Wilmington Learning Collaborative

Any typically stale, procedural tone of the budget hearing broke before his voice did.

Rep. Nnamdi Chukwuocha didn’t have a question when he turned on his mic, looking, like the rest of the Joint Finance Committee, across podiums at the new collaborative director. After the hearing discussion had already stretched past its allotted time on Feb. 14, the Democrat and lifelong Wilmingtonian weighed in, too.

“The level of collaboration and partnership that you have brought in six months, I've never seen,” he said, eyes locked on Burgos. “I've never seen anything close. ... You’ve built a level of trust with principals, our superintendents, school board members, representatives in the city of Wilmington. They believe in the WLC. And this time last year, they didn’t.”

Chukwuocha called this a true opportunity, healing from decisions that hurt generations of Wilmington kids. “Poor decisions,” he said through budding emotion, “that this very body made.”

But first, the Wilmington Learning Collaborative needed a base.

Christina, Brandywine and Red Clay Consolidated school districts saw reviewers on-location in each of their affiliated schools this school year, alongside focus groups and family surveys looking to capture the early state of the collaborative. Educator leadership teams took shape in each building. Monthly meetings have begun between principals who hadn’t all met before, while weekly calls now gather all superintendents.

Education roundup, ICYMI: Delaware schools say state must focus on improving student literacy

Students going to school in the city often face higher rates of poverty, crime and housing insecurity, supporters of the collaborative have said, while such challenges aren't experienced outside the city to the same degree.

Burgos hopes coming school scorecards will answer questions on student opportunity and needs — alongside sending a clear message on Wilmington’s present landscape.

“This is not a matter of 'let's implement a few programs and everything will be fine,' ” she said. “This requires a systemic overhaul. We have to do everything differently.”

Actions could span from full curricula audits; boosted, consistent wraparound services — like afterschool programs or school-based health services — solidifying community councils and more. The goal remains for a more unified approach to delivering the same quality of education across schools.

This planning year also has come with simply trying to build an identity for the new governing body. A website remains in the works, hoping to serve as a consistent home for each of the city schools.

From there, Burgos told lawmakers to expect the work to ramp up.

“That's where we need to start, with this mindset shift that our children are capable,” Burgos said. “The standardized test scores, the data we look at day-to-day is not indicative of our students’ brilliance and genius — but an indictment of the many systems that have failed our communities for generations.”

Flashback to 2022: Can this educational group solve absenteeism and other challenges facing city students?

Where does Wilmington go from here?

Well, Burgos hopes it's an overhaul.

Wilmington certainly has a long, messy history with education. Previous reports on reform in Delaware already have referred to the city’s public education as “fragmented” and “dysfunctional.” After 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, decades of “back-and-forth” on desegregation led to the city’s division into four school districts, leaving inequities to fester between city and suburban schools.

By 1995, a federal court ruling lifted the federal desegregation order and allowed for a school choice system and charter schools to form. Then, in 2000, the passage of the Neighborhood Schools Act directed districts to assign students to public schools that were closest to their homes, as previously reported. With the charter and choice laws in place, abled parents could instead decide to send their children to the suburbs, which led largely to the creation of “racially identifiable high-poverty schools,” according to the Redding Consortium.

Basically: “Our schools are segregated,” Burgos said. “Our communities are segregated, which has certainly shaped the dynamics and hindered the strength of the fabric of our schools. And we need to rebuild that.”

No accident: Wilmington, Delaware, has long, messy education history

Wilmington Learning Collaborative plans to see the first of its reports in March begin to lay a path forward, with more challenges and investment ahead.

Burgos believes that also will include a need for greater autonomy for the new governing body overall.

She doesn’t imagine it will be easy to demand more for the city’s students.

She can, however, put it simply: “We cannot normalize failure.”

Got a story? Kelly Powers covers race, culture and equity for Delaware Online/The News Journal and USA TODAY Network Northeast, with a focus on education. Contact her at kepowers@gannett.com or (231) 622-2191, and follow her on Twitter @kpowers01.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: New WLC leader eyes need for 'systemic overhaul' in Wilmington schools