The deaths of Richard Henderson and Joseph Zadroga were tragic. What can we learn? | Kelly

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Any unexpected death is sad. But the untimely loss of two good men in recent days is profoundly tragic.

Richard Henderson died on a subway car on Sunday night in Brooklyn. Joseph Zadroga died the day before in a parking lot at a rehabilitation center near Atlantic City.

Both deaths were needless — and that’s an understatement.

Henderson was shot to death when he tried to break up a fight between two subway passengers on Sunday evening. Zadroga was about to step into his car on Saturday afternoon, after visiting his wife at the Bacharach Institute for Rehabilitation in Galloway Township, New Jersey, when police say an elderly man behind the wheel of an SUV accidentally hit the gas and plowed into him.

Such are the basic facts about how these men left us. What’s important to remember is how they lived. And understanding that part of this tragedy underscores why their losses are so distressing.

Mike Kelly from 2017: Five portraits of lives forever changed by 9/11

Richard Henderson 'radiated warmth and joy'

Henderson, 45, made his home with his family in Brooklyn but worked as a crossing guard at a private school in Manhattan. To say he was beloved at the World School on 10th Avenue in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood doesn’t really do justice to the way he interacted with students.

Henderson was known as the guy who not only guided students across the street near the school, but acted as an unofficial security guard during recess. Students say he routinely fist-bumped everyone as they walked into school. During breaks, he was known to push young students on swings.

In a statement, World School’s head, Judy Fox, said Henderson “was an amazing man who radiated warmth and joy.” Fox went on to note that he also seemed to embody a sense of duty that wasn’t part of his formal job description, often checking nearby parks after the children returned from recess to make sure no one had left anything behind.

“He came to work each day with a warm smile on his face and a kind word for all he came into contact with,” Fox said in her statement. “He made everyone feel special, cared deeply about our students, and was devoted to their safety and well-being.”

After news of Henderson's death spread, students left bouquets by a wall outside the school, with a poster asking passersby to write personal sentiments. The school also started a GoFundMe page to raise money for Henderson’s wife, three children and two grandchildren. Within days, more than $250,000 had been pledged — with more likely to be promised.

More: Brooklyn man fatally shot inside NYC subway train tried to break up fight, reports say

Joseph Zadroga's legacy of respect and love

Joseph Zadroga left behind a similar legacy of respect and love.

Zadroga, 76, had been a cop in North Arlington, New Jersey, for nearly three decades — his final years as the department’s chief — when he retired in 1997. He then devoted several more years to teaching new recruits at the Bergen County Police Academy in Mahwah, New Jersey.

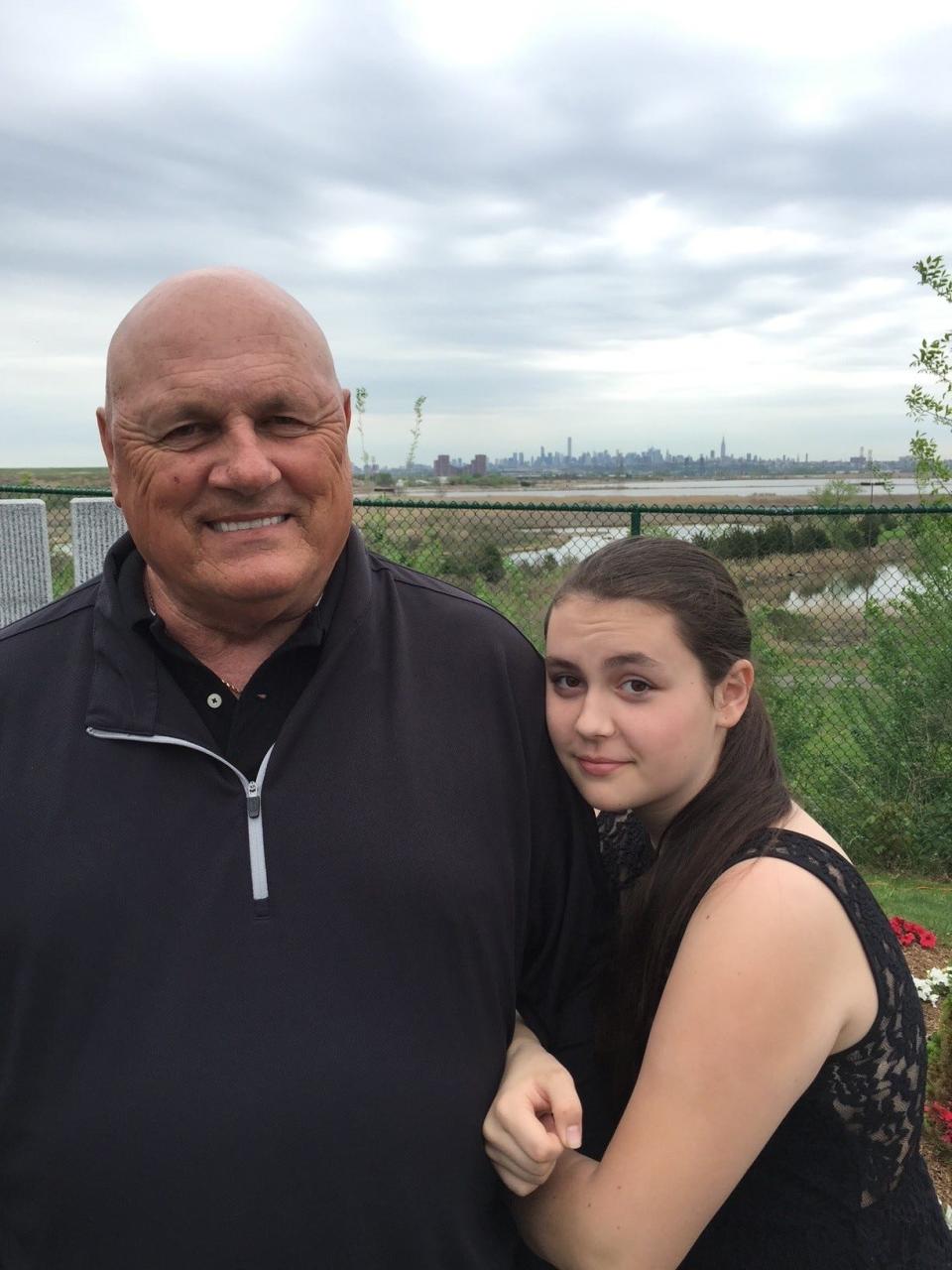

With his wife, Linda, Zadroga moved to Little Egg Harbor, New Jersey, to a spacious home that overlooked the peaceful marshes on the edge of Barnegat Bay. An avid fisherman, Zadroga kept a boat docked during the summer months just a few feet from the back door of his house.

It was here that the quiet retirement that Joe and Linda Zadroga planned changed dramatically.

Their son, James, wanting to follow his father's career, had joined New York City’s police force. When the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, took place, James rushed to the rubble of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, laboring for weeks with other first responders in search of the remains of the more than 400 police officers and firefighters who died there. In just three weeks, he worked more than 500 hours — basically round-the-clock.

James, who had been promoted to detective in the NYPD, soon developed severe respiratory problems. At the time, few experts knew how toxic the air at the trade center’s rubble had become. Soon, however, scientists learned of a terrible new tragedy that would eventually take the lives of thousands of people — including hundreds of first responders — and require thousands more to be regularly monitored with annual medical exams.

The most famous victim was James Zadroga. His lungs were filled — doctors later said “caked” — with all kinds of toxic matter from Ground Zero. Meanwhile, James’ wife, Rhonda, suffered a heart attack and died.

James was left with the couple’s daughter, Tyler Ann, then only 1 year old.

James could hardly walk without someone helping him. He retired from the NYPD on a disability and was living at his parents’ home in Little Egg Harbor.

On Jan. 5, 2006, he collapsed there and died. Tyler Ann was only 3 years old.

Joseph and Linda stepped in to raise Tyler Ann, who is now in her 20s.

“I just sit here at night and cry,” Linda told me when I visited the home a dozen years after James died. “I have to be strong for Tyler Ann.”

Besides their new parenting role, the Zadrogas faced another challenge. Their son was not counted as an official 9/11 casualty.

The Zadrogas mounted a national campaign to draw attention to the health problems that took the life of their son. New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg opposed them. So did the NYPD, refusing even to send an honorary contingent of officers to James’ funeral in North Arlington.

“We’re angry,” Joe told me during that visit in 2017. He mentioned how his son was “my fishing buddy” and had been a terrific police officer in his own right.

“He loved being a cop,” Joe said that day. “He was the kind of guy who could sit down with somebody and within five minutes would know their life story.”

Joe Zadroga did not give up on his son’s legacy. He lobbied Congress and the White House and all manner of media. And eventually, the Zadroga Act was passed and signed into law, guaranteeing federal health care funding for decades for first responders and others who developed medical problems from the poisons of Ground Zero.

More coverage: Joseph Zadroga, advocate for first responders of 9/11, struck and killed in NJ parking lot

Let's remember these men for their many good deeds

As news spread this past week of Joe Zadroga’s death, many friends remembered how he changed the lives of so many first responders who rushed to the smoke and fire of Ground Zero and were wounded with massive and often mysterious health problems.

The same is now true of Richard Henderson and the legacy of care he left among the students and staff members at his school.

Sadly, both men died far too early — Henderson from the bullets fired by an angry man and Zadroga pinned under the weight of an SUV driven by an 82-year-old who police say may have pushed the gas pedal instead of the brake as he tried to find a parking space.

May the memories of both men be framed by their good deeds.

Mike Kelly is an award-winning columnist for NorthJersey.com, part of the USA TODAY Network, as well as the author of three critically acclaimed nonfiction books and a podcast and documentary film producer. To get unlimited access to his insightful thoughts on how we live life in the Northeast, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kellym@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: What can we learn from deaths of Joseph Zadroga and Richard Henderson