Here's how 2 investigators solved the 34-year-old Kelle Ann Workman cold case

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For the majority of the last two years, Leslie Albrecht and Christopher Holland have been working out of one box, a box that Albrecht compared to "Swiss cheese" due to the number of figurative holes.

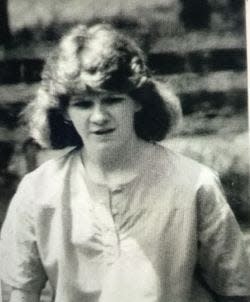

The box, which belongs to the Christian County Sheriff's Office, was all that remained of the evidence from the cold case of Kelle Ann Workman. In the summer of 1989, the body of 24-year-old Workman was found in the Mark Twain National Forest after the young woman had been missing for a week. For nearly 35 years, Workman's family, local law enforcement and community members had been searching for answers to Workman's case. Now, they believe they have them.

The Douglas County Sheriff's Office and Christian County Sheriff's Office announced Wednesday that three men have been charged with Workman's murder: Leonard "Dwight" Banks, Bobby Lee Banks and Wiley Belt. A grand jury indictment filed in the Circuit Court of Douglas County on Wednesday charged Bobby Banks with the murder, kidnapping and rape of Workman. Dwight Banks and Belt are accused of acting alongside Bobby Banks in the crimes.

More: After 35 years, 3 men charged in relation to 1989 Ozarks murder of Kelle Ann Workman

Albrecht, a retired detective of the San Diego Police Department with a history working in both the sexual assault and elder abuse units, and Holland, a retired FBI special agent, first learned about Workman's case in 2019. After years of "blood, sweat and tears," the two found the case's "missing piece," resulting in the arrest of the Bankses, who are brothers, and Belt.

This "missing piece" was an eye witness who law enforcement and investigators were in contact with previously but who was not a suspect. The name of this individual was not released, as this information will be key to an upcoming trial.

The News-Leader contacted Douglas County Sheriff Chris Degase and Christian County Sheriff Brad Cole for comment on working with Albrecht and Holland but was unsuccessful in reaching them.

"500 pounds of pressure" released

Ahead of the public announcement, Degase visited the Workman household Tuesday night to share the newly found information, Pam Workman, Kelle's sister, told the News-Leader. The night was, understandably, an emotional one.

"I wasn't surprised, but it was just like 500 pounds of pressure was released from all of us," Pam told the News-Leader on Friday. "We were all pretty quiet and speechless ... because we couldn't believe, after 35 years, that we were finally hearing the names of the people who were responsible. I told Chris Degase, 'You know Chris, we don't know what to say, we don't know how to act because honestly, we never thought this day was going to happen.'"

Learning about Kelle Ann Workman

In 2019, Albrecht and Holland worked together for the Department of Health and Senior Services Bureau of Special Investigations, assigned to case loads in southwest Missouri. Their work entailed investigating cases of elder abuse and dependent adult abuse. While on assignments together, the two often swapped cold case stories and one day, they began discussing Workman.

Workman was last seen at 6:15 p.m. on June 30, 1989, mowing grass at the Dogwood Cemetery near the Pleasant Southern Baptist Church in Douglas County. On July 7, 1989, her fully-clothed body was found half submerged in a creek in the Mark Twain National Forest, about 12-15 miles from the cemetery. Due to her body's quick decomposition, authorities were unable to identify the cause of Workman's death.

Without a doubt, Albrecht and Holland were interested in investigating Workman's case, but they needed permission from the DHSS.

"We had to find a way to fit Kelle into our wheelhouse to be our victim," Albrecht said.

After speaking with the Workman family, Albrecht came to the conclusion that Workman, who was described as "extremely shy, naive and had trouble socializing," likely had undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder. Although Kelle Ann Workman was independent and capable of caring for herself as an adult, Pam Workman said during grade school, her sister did attend a few special education classes.

With this "diagnosis" and knowledge that Kelle Workman lived as a dependent adult (it was known she lived with her parents), Albrecht and Holland were able to pursue her case as DHSS investigators.

Working closely with the Christian County Sheriff's Office and Workman family, Albrecht and Holland began sifting through that box of evidence that had not been uncovered since 1995. Albrecht said many of the people they wished to interview, including witnesses, members of law enforcement and the doctor who performed the autopsy on Workman's body, had died. Forensics from '89 were not helpful, either. But by far the hardest part of investigating the case was keeping their work quiet while operating in such a small community, Albrecht said.

More: What happened to Kelle Ann Workman? Here's what we know about 1989 case, 3 men charged

For the Workman family, the two years of Albrecht and Holland's investigation were an "emotional roller coaster," Pam said.

"We would go for a month and I would hear from her (Albrecht) every week and then we'd go for a month and it was like nothing," Pam said. "She and Chris both made it very clear from the beginning, 'I'm going to ask you questions, but you can't ask me questions because I don't want to do anything to jeopardize this.' Every time I would start to feel like, '(Gosh darn it), nothing's going to happen,' I would think, 'You know what? We're not going to give up. Maybe this is the time something is going to happen.' And sure enough, here we are."

It wasn't until their second year of investigating that Albrecht and Holland met with the eyewitness who ended up providing crucial information that solidified the case against the Banks brothers and Belt. Within a few months of this revelation, the indictment came.

A search through News-Leader archives does not populate any coverage about Belt's tie to the case over the years, but Albrecht said he was interviewed by law enforcement in the past.

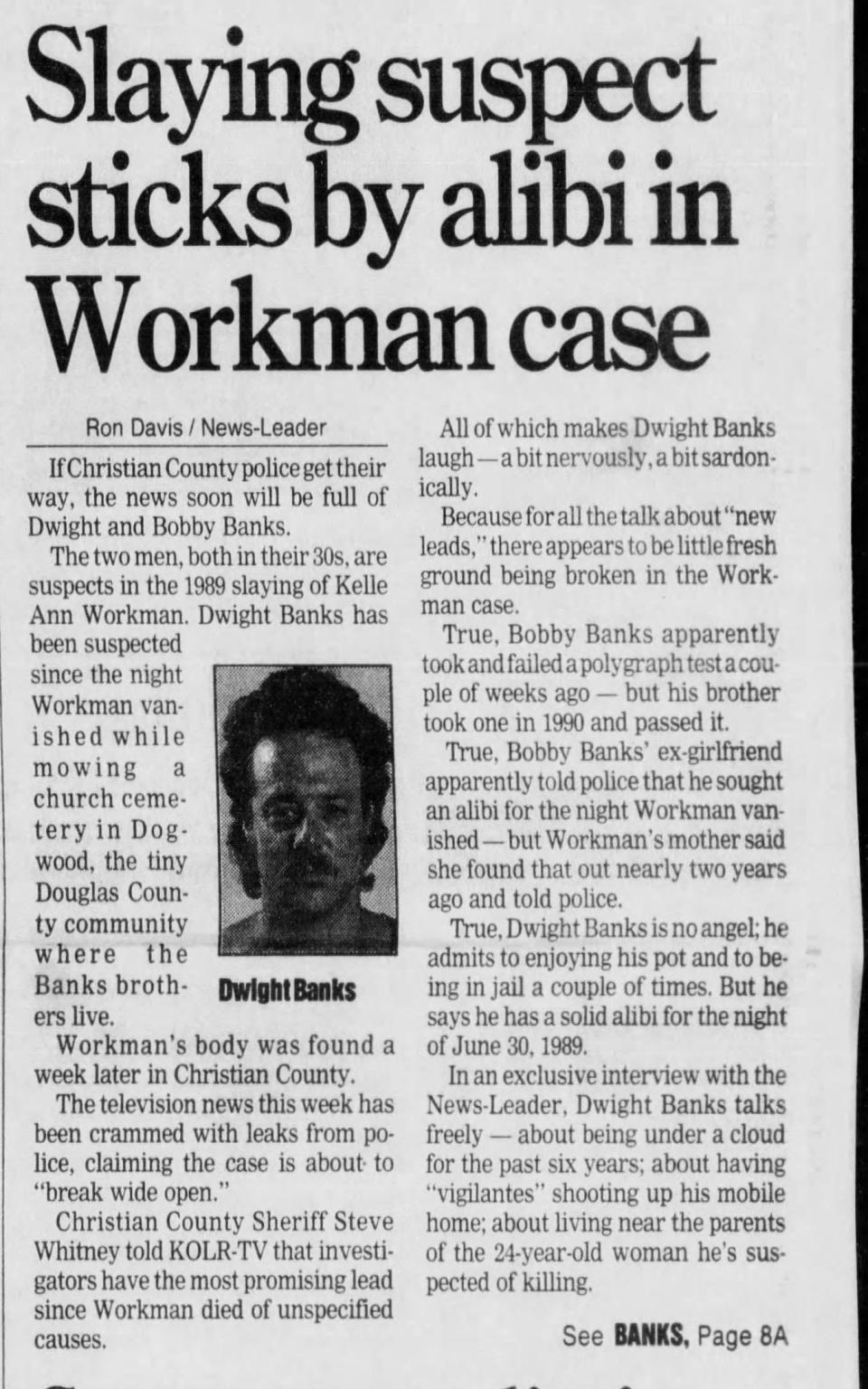

The Banks brothers, on the other hand, were mentioned in the media a few times over the years. In 1995, Dwight Banks spoke with the News-Leader about the case. Bobby Banks declined comment, as he was advised by a lawyer.

In 1990, Bobby Banks failed a polygraph test administered by the Missouri State Highway Patrol, which Dwight Banks said was due to "frail emotions." An ex-girlfriend of Bobby Banks also told the authorities that he sought an alibi for the night Workman vanished.

"The people who came forward, who ended up really being a major turning of this case did it after we originally spoke with them," Albrecht said about the eyewitness. "I think we got under their skin ... not in a bad way. But they were like, 'OK, it's time.' That person contacted us and we went running. And we knew right then, when you have done this as long as we have ... you know when you see real trauma."

More: With 3 suspects arrested, here's a timeline of the Kelle Ann Workman case

Recalling the two years she spent investigating Workman's case, Albrecht got emotional.

"All the times I've been up there (near Dogwood Cemetery), tromping around and I would just sit in that parking lot and look over at that grave and tell her to talk to me," Albrecht said, with tears in her eyes. "I just felt her. I can't tell you. I felt like Kelle, after 34 years, said, 'OK, it's time.' I think she was patient."

Throughout the investigation, bringing more peace of mind to the family remained top priority. Now that a trial, or possibly three, is ahead Albrecht said she has been preparing the family for what's to come and make them feel like they are still a part of the case.

"Our promise to the Workmans is this, and it's our promise to everyone we work for — we're going to do our best to bring answers and justice," Albrecht said. "We never say we're bringing closure, we don't, because with our experience, we know that you can't ever expect a family to have closure."

A desire to help rural communities

While Holland still works for the DHSS, Albrecht left in September 2023 and now has her personal investigator, or PI, license. Although the two may not be working with each other day-to-day, Albrecht said they hope to continue working through cold cases in the region.

"We have lots of experience in a field that the resources out here don't permit. It's not these agencies' fault," Albrecht said. "Some of these agencies have less than a dozen people in the entire office. How are they going to afford to send people to a specific major case investigation team? I've had hundreds of thousands of dollars poured into my training from San Diego PD. I want to use it until I can't anymore because I love what I'm doing.

"We don't sweat the bigger cities so much — not that we wouldn't help, but that's not our focus. Our focus is where the resources aren't there," Albrecht added.

Moving forward, Albrecht said she and Holland are already in talks with another local family in relation to a cold case. But as far as The Springfield Three goes, Albrecht said she does not plan to take the renowned case on with how much investigative work has already been completed.

"Our goal is to get to where there's just nobody trying," she said.

Greta Cross is the trending topics reporter for the Springfield News-Leader. Follow her on X and Instagram @gretacrossphoto. Story idea? Email her at gcross@gannett.com.

Marta Mieze covers local government at the News-Leader. Contact her with tips at mmieze@news-leader.com.

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: These investigators spent 2 years solving 1989 Kelle Ann Workman case