How does the body react to ketamine — the drug used on Elijah McClain during fatal arrest?

One of the many disturbing police brutality cases to be revisited during the national groundswell of Black Lives Matter support has been that of Elijah McClain — the 23-year-old massage therapist and violinist from Aurora, Colo., who was minding his own business and walking home last year when his quirky manner and appearance inspired someone to call the cops on him, leading to his death.

And one of the most alarming details of his case was that it involved the administering of a powerful anesthetic, ketamine, by Aurora Fire Rescue, who allegedly arrived on the scene at the behest of police and injected McClain — who reasonably panicked when police officers became aggressive and put him in a chokehold — with 500 mg of the drug. The injection, which was enough to sedate a man twice his size, may have played a part in the death of McClain, who went into cardiac arrest on his way to the hospital and later died.

“Officers tackled 23-year-old Elijah McClain to the ground, put him in a carotid hold, and called first responders, who injected him with ketamine. He had a heart attack on the way to the hospital, and died days later, after he was declared brain dead.” https://t.co/tB4RSpM3uR

— Saeed Jones (@theferocity) June 25, 2020

So how did ketamine, a drug used in high doses as a medical sedative and in low doses to combat depression (and, illicitly, as a party drug) get involved in this arrest? While it also played a prominent role in Minneapolis — where police allegedly directed EMTs to inject ketamine into dozens of suspects in 2018, leading to an investigation that further revealed suspects were being enrolled in a ketamine study by Hennepin Healthcare without their consent — overall, it’s an uncommon situation. That’s according, at least, to Maria Haberfeld, co-director of the NYPD Police Studies Program at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, who tells Yahoo Life that using ketamine to sedate suspects is “practically unheard-of.”

But, she notes, “There is nothing general about American law enforcement, with over 18,000 different depts., 97 percent of which are small police departments with less than 50 police officers… I’m not surprised to find anything and everything, because there are no standards.”

And while the use of ketamine on suspects is reportedly legal in Colorado, Haberfeld, who has studied police standards and misconduct for over 20 years, notes that it is not an accepted or legal practice in New York or in any major city. “I have no knowledge of any authority, whatsoever, on the part of police to require the EMTs to engage in any specific medical intervention [or] if this is legal or not in a given jurisdiction.”

But it is clearly happening, at least in Aurora and Minneapolis. So, what is ketamine anyway? What is it used for, typically, what are the risks and how might it have contributed to the death of McClain? We asked some experts on the drug to explain.

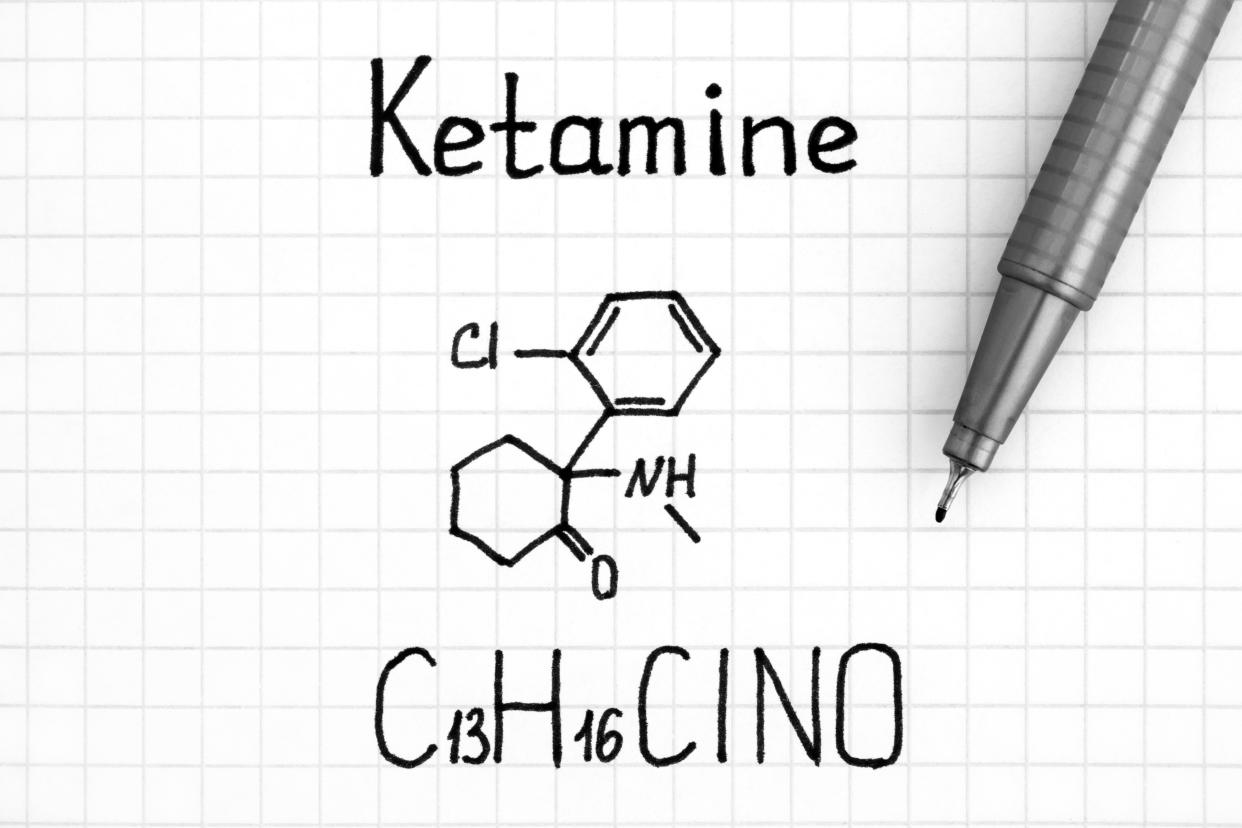

What is ketamine — and is it the same as the so-called horse tranquilizer used by vets and the party drug known as K?

“Ketamine was originally developed as an anesthetic agent in the 1960s, and gained popular use starting in the ’70s … as a field anesthetic during the Vietnam War and others because it’s very safe to administer in terms of having adverse effects on respiration,” explains ketamine expert Gerard Sanacora, a professor of psychiatry at Yale University and director of the Yale Depression Research Program. It’s officially in the class of “dissociative anesthetic” drugs. And, yes, all three versions of ketamine — also known as ketamine racemic mixture or ketamine hydrochloride — are one and the same.

What are the accepted medical uses of ketamine?

In addition to being a general go-to anesthetic in operating rooms and emergency rooms, Sanacora says, “more recently, it’s become very commonly used for pediatric emergencies. And it’s gained a lot of attention in the past decade or two because it’s been shown to have rapid onset of antidepressant properties.” In 2019, the FDA approved a derivative of ketamine — esketamine, in the form of a nasal spray — to treat depression. Further, adds Sanacora, referring to the McClain case, “it’s come under real interest as a rapid induction sedative.” And, notes Alan Schatzburg, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University who has urged caution in the use of ketamine for depression, “It’s also been used in certain clinics for severe chronic pain treatment.” The main difference for each use lies in the dosage, as well as the route of administration — intravenously, orally or, as in McClain’s case, by intramuscular injection. (As a party drug, it is typically cooked into a powder form and then snorted.) For antidepression use, for example, small, controlled doses are administered, while larger ones are needed for sedation.

Related video: Here's what we know about the death of Elijah McClain

What are the physiological and psychological effects of ketamine on a person?

“It’s not a straightforward drug,” notes Sanacora, explaining that the main effects come from how it seems to bind to the brain’s major neurotransmitter of glutamate, blocking the activity, and initiating “a whole cascade of events,” depending on the dosage. “At lower doses, the drug can be excitatory — it can excite brain regions and cause an increase in metabolism. Animals tend to move around a lot more … people become a little bit more disinhibited,” he explains. But at higher doses, it becomes much more sedating, decreasing activity in the brain and taking on sedative and anesthetic properties. It is fast-acting, he says, and “has a short half-life and is metabolized quickly, so most of the time it’s gone within a couple to a few hours of taking it.” Schatzburg adds that the dose for “agitation” is high, at 4 mg to 5 mg per kilo, with which a patient “will fall asleep in six minutes.”

What are the risks associated with ketamine?

Short-term risks can be either physiological — usually a transient increase in heart rate or blood pressure with a lower dose, or, with higher doses, a “relatively low risk of” respiration problems — or psychological. “So, in some patients, [low doses] could create a feeling of anxiety, and really change your perceptions and cognition so you may not be thinking clearly.” Long-term risks come more with the high-level abuse of ketamine and can include bladder or gastrointestinal problems.

There are higher risks involved in an out-of-hospital setting, when the individual’s medical history or current situation is unknown, as with McClain. “There is definitely a higher risk, and there are many studies showing a higher risk of intubation when drugs are given in the field … [where] you’re not able to do blood work or an EKG to try to understand the situation.” But the flip side, he says, is that by doing nothing in a situation when someone is highly agitated, “there’s a real risk too.” Schatzburg says that before learning of the McClain incident, “I never knew that it was used this way.” The 500 mg, he adds, “is a whopping dose.”

Does it make sense for EMTs to use ketamine sometimes to forcibly sedate individuals?

That depends. “This is a really difficult thing ... and the true definition of a dilemma, the worst thing for a clinician or EMS, when you’re called to someone who is highly agitated and you can’t figure out what is going on,” says Sanacora. When someone is in a state of “acute agitation,” sometimes referred to by police and EMTs as “excited delirium,” he says, “there is a relatively high mortality and morbidity risk, so people in those states run a risk of 5 percent to 10 percent of having a really bad outcome ... [so] there is some pressure to take care of that quickly.”

Physical restraint, Sanacora explains, “is not necessarily the best thing, because part of the physiology that’s actually going on during this is called autonomic dysfunction, which is the way the body is normally keeping things in control. Your temperature, your blood pHm, your heart rate — is in many cases out of control, so a person can become hypothermic [or suffer from] metabolic acidosis,” a serious acid-base imbalance in the body. Pushing against restraints can cause muscle breakdown, which in turn can release a lot of potassium, which can be damaging to the heart. “So, there is a real urgency to treat someone like that, and just leaving them in that state is quite dangerous. It’s complicated.” The standard sedative injection to be used in these situations, he says, has been an antipsychotic along with a benzodiazepine, but that comes with risks to heart and respiratory function. Ketamine research, meanwhile, “is suggesting it may be one of the safest things you can give in that situation. So it’s not crazy.”

Schatzburg agrees that “people can have excited delirious states where they’re nonresponsive to intervention. That’s real. And there’s a relatively high mortality associated with it.” But he personally believes that a benzodiazepine might bring less risk in these out-of-hospital situations, and worries that if use of ketamine continues in this way, “We are going to have a number of untoward events, if I were to predict.” Referencing what he’s read about McClain, he notes, “With somebody in a manic frenzy, there’s risk. But if he’s just walking along doing nothing, well, there’s not much risk there.”

For the latest coronavirus news and updates, follow along at https://news.yahoo.com/coronavirus. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please reference the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.