DNA detectives: New tech can mean a diagnosis for your child, but not a lot of answers

Eli Kadkhoda was bouncing around his West Los Angeles living room, jumping from cushion to cushion on the sprawling L-shaped couch as “Paw Patrol” (his favorite show) played on the TV.

To a stranger, he was just an energetic 4-year-old. But his mother, Sanam, knew better. She knew what he’d already lost — many of his words, some of his muscle tone, a bit of his balance. And, because of a new collaboration between geneticists across the country, she knew what he is predicted to lose eventually — the ability to walk, to eat and drink, to speak.

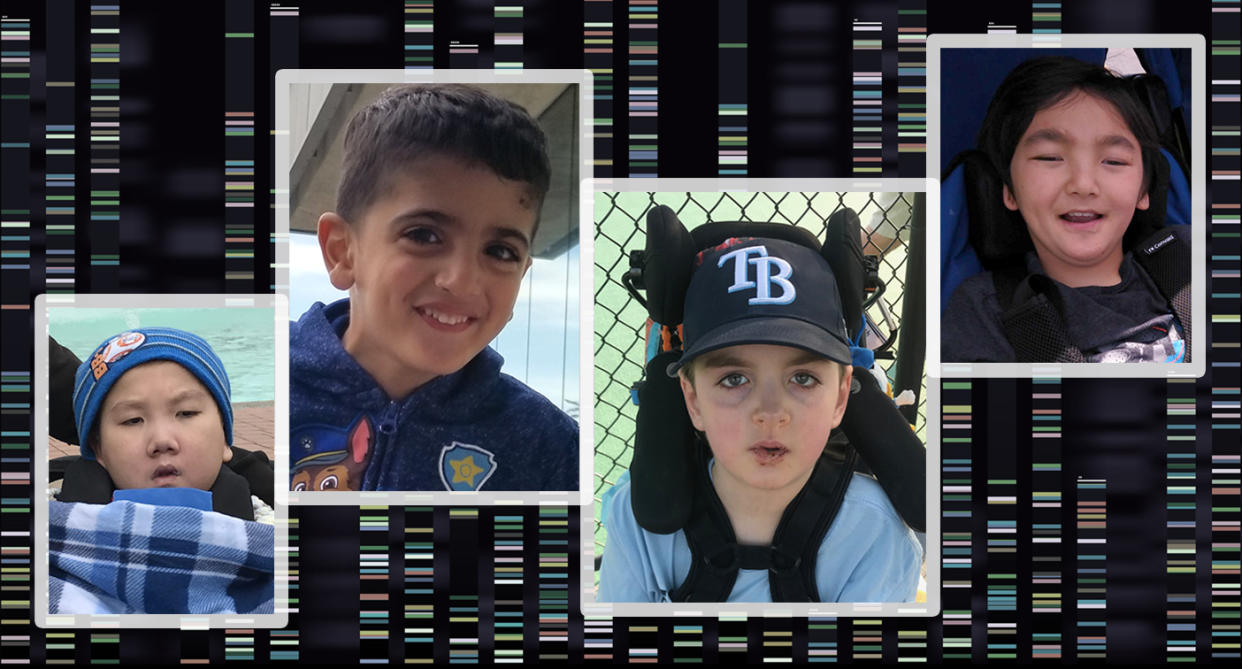

Eli is one of a handful of children found to have a condition discovered so recently it is still called by a number — "IRF2BPL-related condition,” after the gene to which it is linked. The number of known patients in the United States is so small that their parents refer to the other children by their first names: Eli, Caleb, Alex, Leo and Manuel, all healthy at birth, all stumbling and losing speech by kindergarten, all wheelchair-dependent soon after.

As the youngest among them, Eli’s future is foretold by those who preceded him. His parents know what’s likely to happen, and that for now there is no way to stop it. Finding the cause of his condition was a triumph by a new research consortium, the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN). But it hasn’t, at least yet, led to a treatment. As a result, the IRF2BPL-related families are suspended in a scientific moment, one familiar to increasing numbers of patients. They have been handed an answer that leads to more questions; they have a name for their affliction, but not a cure. They have some knowledge, which is a comfort — but also a vexation.

Once a gene mutation is identified, there are a few conditions for which gene therapy is available and others where identifying the gene leads to the use of an already known treatment for a related syndrome.

But mostly there are more families like those with IRF2BPL, learning to live in the in-between.

“We were desperate for a diagnosis and now we have one,” says Cassidy MacKay, whose 8-year-old son, Caleb, was the first U.S. patient in whom a mutation of the IRF2BPL gene was identified less than two years ago. “But it really doesn’t tell us anything yet. There’s no prognosis, no ‘here’s what’s coming down the pike.’ We’re still in unknown territory, but now it has a name.”

Caleb MacKay was born on April 24, 2011. His mother, Cassidy, and father, Todd, had met at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and married in 2004. Todd was a pharmaceutical sales rep, Cassidy was an accountant, and the couple lived with Caleb and his older sister, Lilly, in Greensboro, N.C. Life was good. Soon after Caleb was born, his parents were already talking about a third child, as they both wanted a big family.

For the first 18 months of his life, Caleb “was meeting all his milestones,” though he consistently did so “at the tail end of normal,” Cassidy says. His parents weren’t worried, and neither were his pediatricians. Boys walk late (he did so at 15 months), they all said. Boys don’t talk as early, and neither do second children (his vocabulary was limited for his first two years).

“We figured he was extremely laid back and go with the flow,” Cassidy says. “Though we did wonder if he wasn’t doing things because he didn’t want to or because he was just lazy.”

It was a preschool teacher who first expressed concern at how often Caleb was falling. He was 2½ by then, and it was the first his parents realized that not only was their son lagging behind his sister at the same age, but also his peers. They had their first consultation with a physical therapist, and then with a neurologist, both of whom thought the problem was loose ligaments.

But over the next months, then years, Caleb went backward. Rather than improving on fundamental skills, he lost them, like a film running in reverse. Where once he had stumbled when he walked, soon he could not walk unassisted. For a while after that, he could get around by himself with a walker, but eventually needed a wheelchair. He went to one specialist after another, had every diagnostic test in their arsenal, but only learned what he did not have. He did not have muscular dystrophy. Or a variety of lysosomal disorders. Or Fragile X syndrome. Or Angelman syndrome. Or Niemann-Pick. Or Batten disease.

And still he was losing ground. “We’re never going to go forward,” Cassidy remembers realizing with sudden clarity. “This is always going to be a backward journey.”

Every time she adapted to a new loss, another one loomed. “I’d accept ‘OK, he’s not going to be able to walk’ and then realize ‘now he’s not going to be able to sit independently,’” she says. “Each time it was a surprise.”

In May 2015, when Caleb was 4, he was seen by neurologists at Duke University in Durham, N.C. That summer he had a battery of tests, all of which came back normal, and doctors there suggested a map of his genes via whole-exome sequencing, a relatively new method that identifies mutations in the parts of the DNA that make proteins, called exons. Together the exons are called the exome, and because most disease-causing mutations occur in this part of the DNA, it is a more efficient way to search for those mutations.

Whole-exome sequencing, once prohibitively expensive, can now be done for about $250. Whole-genome sequencing, which scans a person’s entire DNA, can cost as little as $1,500. The increasing accessibility of these tests is a major reason why more rare mutations are being identified recently.

Though faster than it used to be, the method still takes time, and during the months of waiting for results Caleb saw more specialists and lost more function. His limited speech dwindled to a few intelligible phrases. He could no longer sit without being strapped upright.

By the summer of 2016, Duke’s geneticists said the whole-exome sequencing had found nothing.

The news was a particular blow to Cassidy and Todd, who had broken their own rule to take one day at a time and had dared to think about the future. They hoped for a third child. If the results had identified a de novo mutation — one that was not carried by a parent but instead occurred spontaneously in the developing fetus — there would be no reason not to go ahead. Even if the results had identified an inherited mutation, they could use IVF and screen for that mutation before an embryo was transferred.

But despite throwing the formidable power of Duke’s geneticists at their son’s exome, they still had no answers.

“We had always thought we wanted another child,” Cassie says. “But then we started having medical issues with Caleb, and we didn’t talk about it for a long time. At about the time we got to Duke, was the time we also started thinking, ‘If we are going to do this, we have to decide.’”

Their decision tree changed when the whole-exome sequencing came up empty. “We realized what we were deciding was whether or not we could have another child with the same issue,” she says. “And ultimately we decided that if that did happen we would be OK with that. So we said, ‘Let’s try for six months and see what happens.’”

The Undiagnosed Diseases Network was founded by the National Institutes of Health Common Fund “to bring together clinical and research experts from across the United States to solve the most challenging medical mysteries using advanced technologies,” according to its charter.

When it began work in 2015 — at about the same time that Caleb was being seen at Duke — the UDN included seven member sites (there are now 12) across the country that pool resources and findings. Some are clinical sites, where specialists such as endocrinologists, geneticists, immunologists, neurologists and nephrologists examine patients. Some are sequencing sites, where actual genetic mapping is performed. And some do model organism screening — mimicking genetic mutations in fruit flies, mice or worms, for instance, to see if they created symptoms comparable to those seen in humans.

Duke is a clinical UDN site. When Caleb’s results came back without answers in the summer of 2016, two of his physicians, Dr. Vandana Shashi and Dr. Loren Pena (who has since left Duke for Cincinnati Children’s Hospital) submitted him as a candidate for the UDN. His case, Shashi says, is what the network was created for.

“We like to have cases that are hard to solve,” she says. “Seventy-five percent of the ones that got through the UDN come to us with a negative exome,” as Caleb did.

In the fall of 2016, the MacKays spent a week in Durham, bringing Caleb in daily for blood tests, urine tests, clinical exams, MRIs, skin and muscles biopsies, and a repeat of the gene sequencing. Everything, including their travel costs, was paid for by the UDN.

Analyzing an exome is an art. Of the roughly 20,000 known genes, the purpose and function of about 6,000 have been identified, and mutations in 4,000 to 5,000 of those have been linked to a disease. The team does a first sweep of mutations known to cause disease, looking for a match with the patient’s symptoms. When that is negative, as it was with Caleb, it gets interesting. Practitioners compare the subsequent steps to an increasingly intricate internet search — what pops up depends on what key words you enter.

“Every lab has different software; there are many different variables that come into play,” Pena says.

By fiddling with the algorithm, Duke’s biomathematician flagged a gene known as IRF2BPL as worth looking into. Caleb’s version of that gene had a mutation, or glitch, in its code. It had not come up in prior searches because it was thought to be linked to puberty, and Caleb showed symptoms as a toddler. But when the UDN site at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston created a fly model with the same mutation, the affected flies began to regress at about the same stage of development.

How do you determine that a fruit fly is failing to meet its developmental milestones? In this case, flies of a certain age would lose their ability to right themselves in a test tube after it had been violently shaken, and would take longer to climb from the bottom of a vial to the top. If IRF2BPL had previously been thought to initiate at puberty, it now looked as though damage to that gene could essentially reverse puberty — a Benjamin Button of a gene, taking a child who could walk and talk and erasing those abilities.

Cassidy and Todd learned all this on May 19, 2017. By this visit to Duke, Caleb could no longer eat or drink, and was being fed through a gastrostomy tube. “A hypothesis of a (potential) diagnosis,” Cassidy titled the post on Caleb’s CaringBridge site after the meeting with the medical team. “Well, that's how things stand in the medical world,” she wrote of the identification of IRF2BPL, “especially when dealing with rare diseases/conditions and the continually evolving world of genetics.”

When the suspect gene was entered into an international database called GeneMatcher, she’d been told, it led to a research team in France that had identified other patients with the same mutation who demonstrated the same symptoms. The world total was six — two in France, one in Germany, one in Arizona, one in California and Caleb in North Carolina. Five were boys, one was a girl, four were 10 years old or younger, one was 20, and one had recently died at the age of 10 from a seizure.

Their stories were eerily familiar. As Cassidy wrote: “The six were … developing normally until somewhere between age 2.5-4 when they started regressing with significant overall developmental delays, mild speech delays early regressing into more pronounced speech delays, normal MRI, normal diagnostic (blood/csf/muscle/skin/urine/etc) tests, all have shown a slow down on the growth charts (for weight — probably due to feeding issues, but so far only 3/6 have feeding tubes), no distinguishing facial features/look, and none have had significant organ issues (heart/lungs/kidney/etc). There was a little variability in symptoms — 3/6 have had a seizure disorder or seizure activity, 2/6 had frequent ear infections causing ear tubes, most but not all have had some sort of eye/vision problems.”

For the first time, the MacKays knew of patients to compare Caleb with. Now they knew they should be on the lookout for seizures. At the same time, Caleb was the only one of the patients who’d had cognitive testing done — using pointing and eye blinks to demonstrate understanding. The fact that the results showed him with near normal cognition was a valuable bit of information for the other families, who had wondered what their children did or did not comprehend.

Other than that, there was little concrete guidance.

“They do not know anything about how or why this type of mutation on this gene creates the problems it does,” Cassidy wrote. “They can't give us any info on prognosis or outlook or treatment or hope for a cure. And we may never know more. But the hope is that they can one day prove that this gene mutation is causing his problems as that would be the first step in learning more and lead toward potential therapeutics. And we hope that by connecting with others with this IRF2BPL related condition, we can learn from each other, spread awareness and potentially expand the group of 6 to many more to learn even more from others.

“But wow. Learning this really blew our minds. We had given up hope of any answers, so to even get this little piece of the puzzle feels good to us. What a truly RARE disease. We've been calling Caleb a medical mystery ... and for good reason, it turns out.”

In fact, it was beyond rare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a rare disease as one affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. Together, rare diseases affect 24 million people in the U.S. and 400 million worldwide. There is no reliable estimate on how many conditions affect numbers in the single or double digits.

Rare, too, was the fact that the MacKays got an answer. Although genetic answers are more accessible than ever before, they are still elusive. Of the 1,100 cases investigated by the UDN since it was formed, only a third have resulted in a diagnosis.

The Duke geneticists took blood samples from Caleb’s parents and his sister and were able to show that none of them had the same mutation, which means Caleb’s was in fact de novo and not inherited. This was a relief, as Cassidy was already pregnant when the IRF2BPL finding was made. Austin MacKay was born on June 20, 2017.

Announcing his arrival to friends and family, Cassidy wrote: “Caleb is interested in him but doesn’t like when he cries (it makes Caleb cry too — sweet boy).”

Eli Kadkhoda’s parents felt optimistic after their September 2017 meeting with Dr. John Graham, a clinical geneticist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

By the time they’d been referred to Graham, Eli was nearly 3, and for most of his life he had been slow to hit his developmental milestones. It seemed to take Eli longer than other children to learn to roll over, to reach for toys, to crawl, to make the early babbling sounds that lead to speech. He finally learned to walk, but never ran like other children, and often stumbled.

Still, it had been somewhat of a surprise when his older brother’s preschool teacher took his mother aside one day and said, “I don’t want you to get upset by what I’m saying,” Sanam recalls being told. “I spend a lot of time around kids Eli’s age and this is not normal. You need to have him evaluated.”

He was indeed evaluated. Often. His list of specialists soon came to include occupational therapists, feeding therapists, speech and physical therapists. The Kadkhodas were encouraged by the progress Eli made under their care. His speech improved, as did his coordination and his gait. So when Graham suggested whole-exome sequencing, Eli’s parents hoped it would provide another useful tool.

“I thought it would be a matter of ‘he has something where they don’t talk until 4 years old, so no need to invest time in speech therapy, focus on occupational therapy instead,’” Sanam says. She also hoped that genetic testing would give her a name for their son’s condition other than “global developmental delays.”

A few months after Eli’s blood was drawn and sent out for gene mapping, they received the results. “De novo heterozygous on IRF2BPL,” the report said — meaning a spontaneous, noninherited mutation on one of the two versions of the gene in each of Eli’s cells. Although Caleb’s findings had been entered into GeneMatcher a few months earlier, they had not made their way to the lab that had sequenced Eli. The genetic counselor who interpreted the lab report for the Khadkodas, therefore, did not know about Caleb or the other patients around the globe.

So at their meeting with Graham, they were told only that “there is a possible link to seizures, so we should keep an eye out for seizures,” Sanam recalls being told. The family left that meeting feeling optimistic. “For a moment it felt like that was as bad as things would get,” she says.

Soon after Eli’s parents went home, however, Graham was coincidentally asked by a colleague at UCLA to stop in and take a look at a longtime patient. Manuel Martinez was 20 years old, and as Dr. Graham heard the young man’s medical history — born healthy, late to roll, crawl and walk, beginning to stumble and fall at about age 2, increasing spasticity and loss of some speech by age 4 — the story began to sound familiar. Examining Manuel, however, was nothing like examining Eli. Manuel was wheelchair-bound, fed through a tube, unable to hold up his head or communicate. His hands were curled inward toward his body, his feet contracted as well.

“He’s like taking care of a baby,” said his mother, Aracely, who was raising him alone while working nights as a cashier in a local market.

Whole-exome sequencing had recently found a mutation on a gene with which his doctor was unfamiliar — IRF2BPL.

A few days later, Sanam received a call from the genetic counselor at Cedars-Sinai asking her and her husband to meet the next morning. Both the Khadkodas are pharmacists, but it didn’t take experience in the medical field to recognize the note of controlled distress on the other end of the phone.

“Tell me,” Sanam said. “I know you guys have found something. I will not be able to function all day today.”

The counselor told her. That night Sanam searched online for IRF2BPL and found Cassidy MacKay’s Facebook page, with its photos of Caleb. “That made it real,” she says. “There was something familiar about him — the way he held his arms, flexed inward, certain positions that Eli sometimes does. It just hit home at that point.”

Like Manuel Martinez, Caleb MacKay and Eli Kadkhoda, Alex Yiu had appeared healthy when he was born in the summer of 2005. As he grew, he seemed a little bit behind to his parents, meeting his milestones later than his older sister had. He fell more often. His speech was harder to understand.

His mother, Caroline, mentioned this to doctors whenever Alex had a checkup, but no one seemed concerned, and the only diagnosis was “global developmental delay.”

“Everyone kept saying he’ll grow out of it,” Caroline says. “But he seemed to be getting worse.”

Like the other children before him, ones that Caroline had not yet met nor even dreamed existed, Alex’s days began to fill with therapies, tests and visits to specialists. She felt grateful to the therapists but dismissed by the specialists. When Alex fell yet again, resulting in a visit to urgent care, the orthopedist on duty looked at his long chart and joked, “Maybe you should just tie him to a chair?”

“That was the wake-up call that the doctors don’t know what they’re doing,” she says.

As he regressed, his parents adapted. “Every day we tried to handle what happened that day,” Caroline says. “Our lives have been chasing a moving target.” One day he started missing his mouth when using a spoon, so his caregivers began to feed him. Another day he began choking when chewing. They started to purée his food. He enjoyed food, so they waited as long as they could before conceding that his new and frequent seizures made eating life-threatening and had a gastrostomy tube inserted.

Becoming familiar with doctors’ offices in her hometown of San Diego, Caroline also became familiar with a number of families whose children had a list of symptoms but no diagnosis. From them she learned about genetic testing, and she had Alex tested in 2012, but the results came back with no match to a disease. In 2014, she founded the San Diego Undiagnosed Family Support Group, its membership reaching nearly two dozen families. They would hold get-togethers in the park with the children.

Through this group, Caroline and Alex became friendly with Yumi Enoue and her son, Leo. Leo was three years younger than Alex, and the two seemed to be on the same medical path. At 2½ Leo could only say “mama” and “papa.” He could walk and even run, but “his gait was a little clumsy,” Yumi says.

Doctors in San Diego were flummoxed, and during a visit back to their native Tokyo during the summer of 2012 they had him seen at Japan’s premier children’s hospital. By then Leo was falling often, couldn’t stand by himself and had lost much of his fine motor skills.

Japanese doctors had no answers. Back in San Diego, a neurologist ordered whole-exome sequencing in 2015, but while “we found some unknown significant variants, they didn’t fit his condition,” Yumi says.

Then, in 2017, the Enoues traveled with Leo to Los Angeles to meet with an expert in muscular dystrophy. That doctor ruled out that condition, but suggested Leo be seen by Dr. Stanley Nelson at UCLA, a UDN clinical site. Nelson was the physician who had brought Graham in for a consultation on Manuel — the visit that led to Eli’s diagnosis. When Leo’s whole-exome sequencing was redone, it showed a mutation in IRF2BPL.

At the next meeting of the Undiagnosed Family Support Group, the Enoues told the Yius of their diagnosis. Before long, Alex became the fifth patient in the U.S. with IRF2BPL-related condition.

The first peer-reviewed paper about IRF2BPL was published last year, in the American Journal of Human Genetics, and since then a handful of other patients have been added to the global list, bringing it to not quite two dozen.

What difference does this official listing in the medical literature mean to the families?

Everything, and not much at all.

Nearly all the children continue to slip backward. Leo had surgery last week to lengthen his constricted legs. Caleb has been in and out of the hospital all spring and into summer, including over his birthday, when his family had hoped to take him to Disney World. Alex has developed chronic and serious respiratory issues.

All their parents, meanwhile, continue to move forward. Cassidy fought successfully to save the school for medically fragile children that Caleb loves. He still attends every day, now with his new service dog, a golden retriever named Kip. They have chosen not to pay for a genome scan for their younger son, because he shows no signs of the condition, and the odds against another spontaneous mutation is so high. “But a part of me will hold my breath until he is 5,” which, now that there are enough patients to see the patterns, appears to be the developmental cliff.

Sanam is aware of that looming precipice too, and while Eli still seems to have plateaued she knows that is likely an illusion. “People have asked us, ‘Don’t you wish you never had the genetic testing done?’ because every second we’re watching our kid for something bad to happen,” she says. “But really, knowing is a blessing for us. It would be nice to be in denial, but it wouldn’t help Eli, would it?”

The family is looking to leave their picture-perfect home in their beloved West Los Angeles neighborhood, in anticipation of the day when Eli cannot navigate the stairs and becomes too heavy to carry. They have also founded a charity, Stand by Eli, to fund research into a genetic treatment and cure.

Giving her son’s condition a name has allowed her to meet nearly all the American families in the small club, except one. Manuel’s mother only learned from this reporter that there were others with the same diagnosis, and at the end of that conversation she offered to talk to any other parents who might find it helpful to learn how the oldest known IRF2BPL survivor and his family were coping.

Some of the parents plan to be in touch. “Yes, please connect us,” Caroline said.

Sanam, however, is reluctant. “Their son is the furthest progressed of all the children, and I don’t have the courage to talk to them. I just can’t,” she says.

“I am glad I have the information I have,” she continues. “The way I cope with it is by taking it day to day, not looking into the future. Don’t ask me what I am doing next year, because I can’t tell you. There is such a thing as knowing too much.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: