Jacksonville artist Hope McMath uses her work to reckon with the Confederates in her family's past

It was the middle of the night and the bus wasn't moving. It would stay stuck in traffic for another three hours due to a crash farther up a two-lane road in Henry County, Ala.

Jacksonville artist and curator Hope McMath was on that bus, returning home after leading a group tour for the racial justice group 904WARD that went to places connected to the civil rights movement in Montgomery, Ala.

A few years later, she tells of pulling out her journal on that bus, there in the dark, and how she started to write, wondering about how little she knew of her own family's past, particularly her father's side of the family, from whom she'd been estranged since she was a teenager.

Back in Jacksonville, she started digging online, through Ancestry.com and old census reports, military records and newspapers.

What she found were numerous McMaths in southern Alabama and in Georgia, direct ancestors of hers, who had owned and sold enslaved people, who had helped push indigenous people off their lands, who had fought for the Confederacy, who had gone into politics and worked to uphold a racist system of government.

And in her research, Alabama's Henry County repeatedly showed up: "It turns out that spot where we had sat for three hours in the middle of the night was within spitting distance of the homestead that had belonged to my family."

She'd known of none of that. But now, she realized, she would have to grapple with the meaning of that legacy, given that she'd spent years working on issues of social and racial justice.

She could have ignored it, not said anything to anyone, she acknowledged. But she's an artist. So she'd make art about it.

'I'm in this story'

The result is a new show at Yellow House, the gallery she founded in North Riverside in 2017 after leaving the Cummer Gallery of Art & Gardens as director.

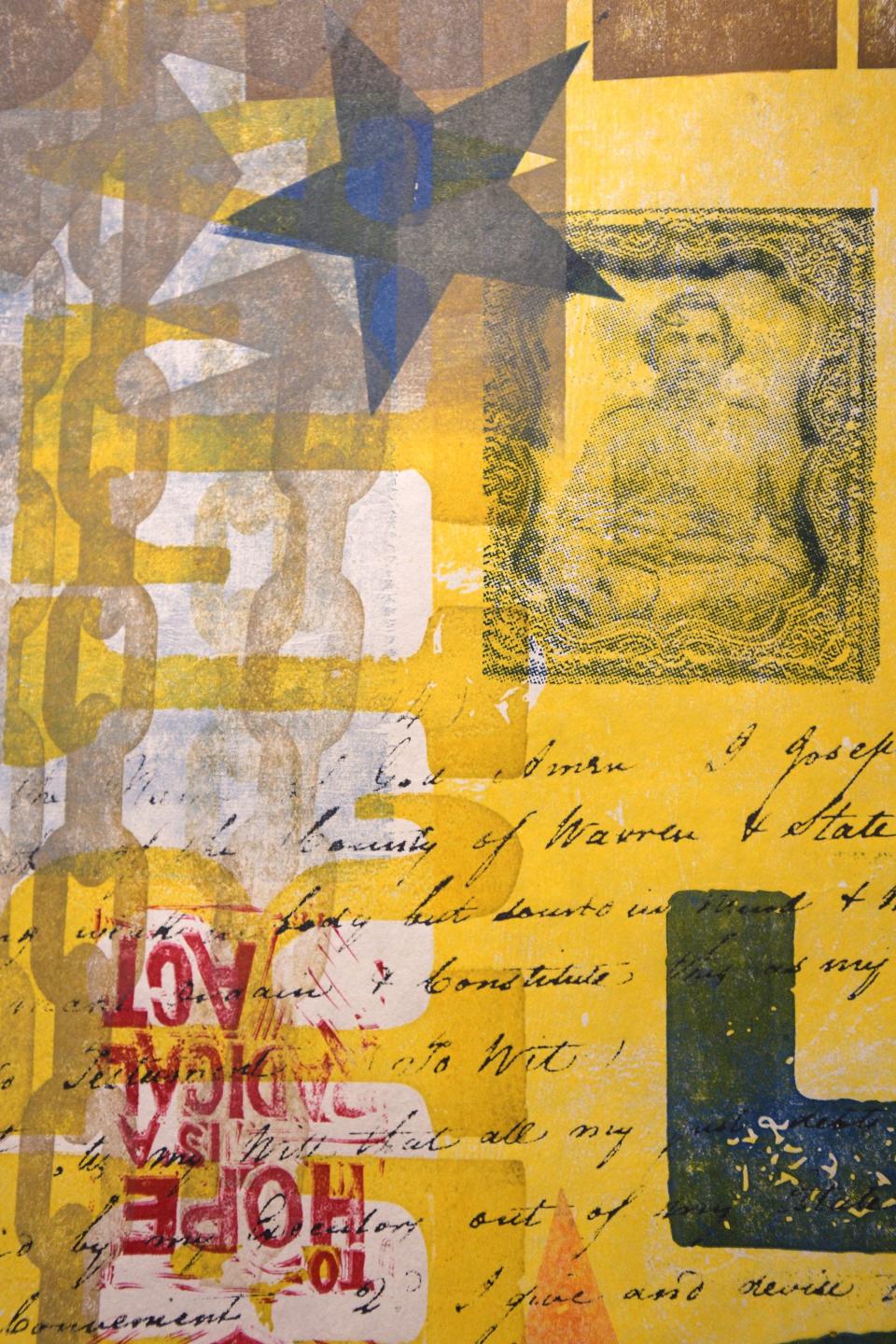

It's called "Legacy Interrupted," and it features some 30 works of art, many of them large-scale prints, in which McMath looks squarely at her family's history and how it ties in with the country's past as well as its present.

She had been a curator of other people's shows, formerly at the Cummer, a Jacksonville institution, and more recently at Yellow House, a place for what she's called “socially powerful art.”

This time it seemed right to make her work the centerpiece of an exhibition.

"I'm in this story, right?" she said. "Not just the voyeur or the person standing at a distance creating art about it. It is me, and this grappling with this stuff, I'm the one doing that."

'Dudes wearing Confederate garb'

McMath is a Jacksonville native. Working on racial justice and social justice issues, she's been to rallies and protests, organized art shows and led panel discussions.

"I'm constantly hanging out with dudes wearing Confederate garb," she noted dryly.

She's wrestled with different thoughts since discovering that part of her family's past.

"I don't walk around with some sort of weird guilt. Shame isn't the right word," she said. "It's more, what is then the responsibility when generations of your family have done harm, significant harm? How does that inform the way I decide to move through the world? What is my role to repairing any of that? I don't know the answer to that, necessarily."

There are three recurring images in the work displayed in "Legacy Interrupted."

One is taken from a small tintype she found of Hachalia McMath, a young Confederate soldier and direct ancestor. He survived the war, though some of his siblings who also fought did not.

"He sort of is a stand-in for my ancestors who were doing a lot of no-good," she said. "Generations of them were enslavers. They pushed indigenous people off their lands, they fought for the Confederacy, they wrote Jim Crow laws. They did it all. Over several generations, they were pretty hardcore."

Another is a depiction of "The Women of the Southland" monument that was recently removed, not without controversy, from Springfield Park, formerly known as Confederate Park. A tribute to the women of the Confederacy, it showed a woman reading to two children.

From December: Confederate monument removed from Jacksonville's Springfield Park early Wednesday

McMath, a member of Take 'Em Down Jax, a group working to remove tributes to the Confederacy from city property, called it a prime example of the Lost Cause movement, which strived to make the South's secession seem a noble and heroic effort. She noted that her research showed that women in her family inherited and owned slaves.

The third recurring image in the exhibit is of Harriet Tubman, who escaped slavery and became a prominent abolitionist. She represents, McMath said, the more than 400 Black people her family enslaved, whose pictures and in most cases names weren't preserved for history.

"Harriet becomes the stand-in for the people I don't know, for the faces I don't have. I know her. We know her story," she said.

The prints in the show are layered with excerpts of census and war records relating to McMath's family, as well as a will made by Hachalia's father, who shared that name. A farmer involved in local politics, he left a will to benefit his wife Elizabeth that included, McMath noted, "the desire to pass along his home, his property, his tools, his cattle and the people he enslaved."

Larger words are also found in the prints: heritage, reckon, hope, reimagine, remember.

Those are the themes McMath wants to explore. "Once we know the wretchedness of our past, what is our responsibility in breaking those cycles?" she said.

At Jacksonville meeting: Black historians 'running to the fight' over state's school rules

McMath said her work is also a reaction to changes in state standards for teaching Black history, part of the so-called "anti-woke" efforts in Florida that would prohibit lessons that cause students to feel “discomfort” or “guilt” based on their race, sex or national origin.

"This work, in part, is a response to that. It's one person saying, 'I'm going to look at this truth, really look at it, the full wretchedness of it, and I'm going to put it out there for other people to see, because we can't continue to look away from it,'" she said. "We have people right now in power who would be very happy for all of us to look away."

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Jacksonville artist reveals family's Confederate and slave-owning past