One of Cincinnati's most bizarre political careers ends in prison

The first questions were raised almost immediately after Jeff Pastor's surprising victory in Cincinnati’s 2017 City Council election.

How did an unknown former substitute teacher, a Republican who had never run for public office, win a seat in a city dominated by Democrats? How did he pay for campaign billboards that sprung up throughout the city? Why was he wearing a Jewish yarmulke at his swearing-in ceremony, despite having been a Christian chaplain in the Navy?

Who, really, was he?

The questions continued after he walked through the doors of City Hall.

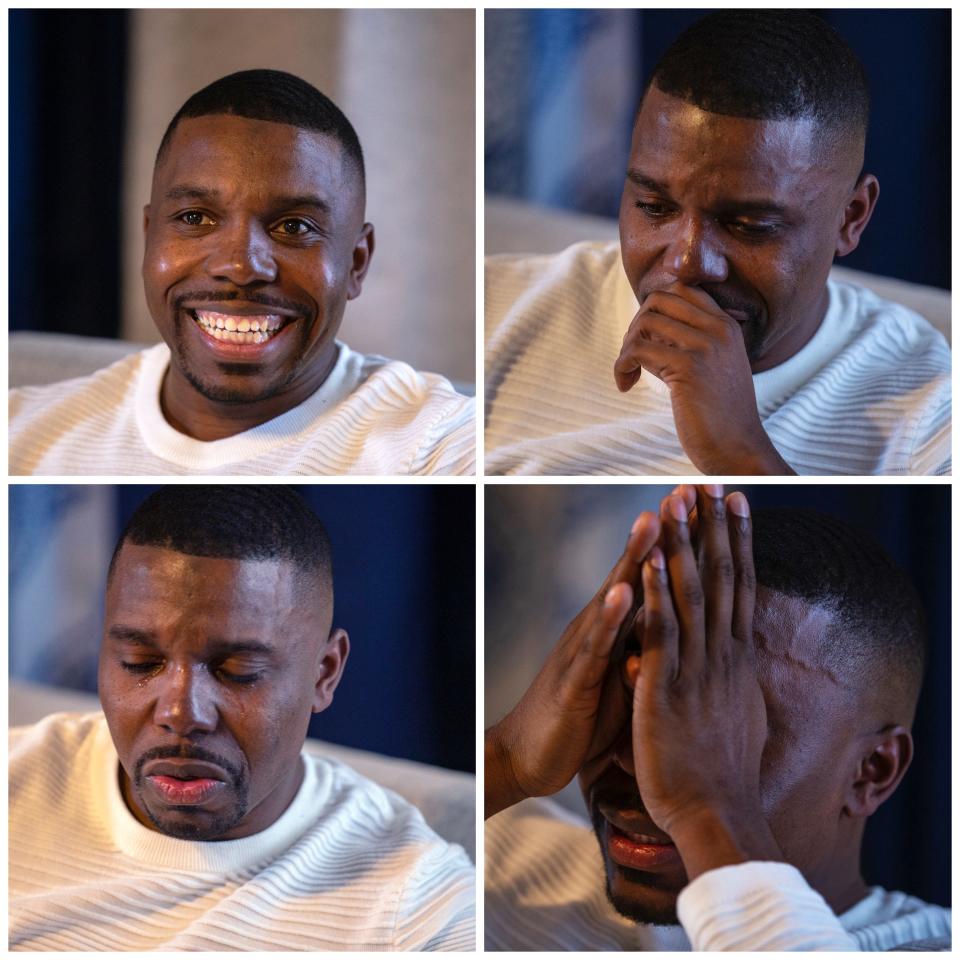

Pastor cried during council meetings, posted shirtless photos of his increasingly tattooed body on social media, and hosted a women-only gun permit class in a church. He even declared in a public essay that he was a "polyamorous" atheist.

Then in 2020, three years into his term, FBI agents showed up at his North Avondale home and arrested him on federal corruption charges after Pastor portrayed himself to developers as a politician who could get things done − for a price.

Pastor, a 40-year-old father of six, pleaded guilty in June to a corruption charge and was sentenced in December to spend two years in prison.

Pastor is set to report to prison on Friday. He requested placement at a federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky, the same prison where former Cincinnati City Councilman P.G. Sittenfeld is serving a 16-month sentence on separate federal corruption charges. It is a low-security facility with an adjacent minimum security camp. However, Pastor's prison placement has not been made public.

The sentencing ends his criminal case, but Pastor remains an enigmatic figure.

"There's a little of George Santos in everything that happened," said Steve Goodin, an attorney and former Cincinnati city councilman who was appointed to replace Pastor after he was suspended.

"Part of me is sympathetic to him,” Goodin added, “because it seems like his crimes were driven by finances.”

Prosecutors alleged that only months after Pastor stepped into City Hall, he was shaking down developers. The scheme involved tens of thousands of dollars in bribes, the creation of a fake charity to launder money and even a free trip to Florida.

He was suspended from City Council and lost his job as director of a local epilepsy foundation. In 2023, his home was foreclosed on to help pay multiple debts, including nearly $28,000 in property taxes.

Pastor is one of three Cincinnati council members who were indicted in 2020 on federal corruption charges. Tamaya Dennard pleaded guilty and already has served a prison sentence. Sittenfeld was convicted by a jury and began serving his sentence Jan. 2.

From Cincinnati's West End to seminary − and Judaism

Pastor grew up poor in the West End. His childhood, by his own admission, was "deeply traumatic" and riddled with "trauma and abuse," according to a memorandum filed before his sentencing. His biological father was not present in his life, and his mother's boyfriend was abusive to the family, which included three younger siblings, his public defender wrote. Pastor graduated from Withrow University High School. While at Central State University, a historically Black university in Wilberforce, Ohio, he started a college Republican organization.

He eventually went to Payne Theological Seminary, also in Wilberforce, with plans to become a pastor. While there, he joined the U.S. Navy Reserve, with a dream of becoming a military chaplain.

In 2010, Pastor graduated from seminary and headed to the Navy. But he learned he needed two years of pastoral experience, and his seminary degree didn't count. He was honorably discharged in 2011, military records show.

In 2013, he took a job with the Ohio Republican Party, working to help then-Gov. John Kasich get reelected.

Around that same time, he converted to Judaism. He would later tell The Enquirer in a 2020 interview that he did it because his faith had been shaken by what happened in the military.

His time with Ohio's Republican Party came as the national party was pursuing local initiatives to engage Black voters.

He traveled around southern Ohio to meet and talk with voters. He got to know prominent Republicans and started to think about running for office.

Pastor eventually began focusing on his own political career, and in 2017, he ran for City Council.

In the early days of the campaign, Pastor said he was a substitute teacher. But later it came to light he also was working as executive director of a nonprofit.

Pastor had met Charlie Shor, a wealthy businessman who had a charitable foundation dedicated to epilepsy research. Shor hired Pastor to run the foundation in 2016.

Pastor was elected to City Council in November 2017, narrowly winning the ninth of nine seats by 223 votes. At his swearing-in, he wore a yarmulke, a traditional Jewish cap.

His election was not expected. Republican insiders knew him, but he had never been involved in city politics and was not known to the public. Cincinnati also had become a Democratic city.

Pastor, according to his sentencing memorandum, "viscerally" understood and empathized with those "living on the fringes of society."

"Mr. Pastor saw city council as an opportunity for him to give voice to the powerless and to effect change on systemic levels," the memorandum noted.

Where did Jeff Pastor's campaign money come from?

Almost immediately, there were questions about Pastor's win.

Some wondered how he paid for billboards that sprung up around the city shortly before the election. People also asked how he was able to buy a half-million-dollar house in North Avondale.

And there were questions about Pastor handing out checks during the campaign for thousands of dollars from the foundation he ran to Black churches in the city − a move one of his opponents saw as an attempt to "buy the vote."

Publicity about those problems led him to leave Shor's foundation.

He went from earning six figures a year to a $60,000-a-year city council salary.

Pastor's sentencing memorandum said Pastor always set out to do good for his community.

"But when fear and insecurity related to housing, food and safety are so visceral from having been so much a part of the fabric of his childhood when no generations-long safety net exists to help in moments of need, something like losing a job and not knowing how the mortgage will get paid, adversely affects decision-making in terrible and aberrant ways that, as here, have lifelong effects."

Katie Eagan Downing, who oversaw his work with the state Republican Party, said she would occasionally talk to him when he was on council and found him to be the same engaging person she first met.

"He was easy to work with. Very friendly. Very personable," Downing said. "He was well known to party operatives. He knew the right people. He knew how to get elected. He knew who to talk to."

Downing said when she heard Pastor had been indicted: "I was sad for Jeff, because it was a lot of wasted potential."

Private jet to Florida, a 'monthly retainer' request

Pastor's scheme to earn money from his council seat began in June 2018, six months after he took office, court documents say.

The investigation ultimately would involve undercover FBI agents and two city real estate developers, one who has never been publicly named. The other developer was Chinedum Ndukwe, who also was a cooperating witness in the Sittenfeld case. That development centered on a vacant building at 435 Elm St. in Downtown.

By September 2018, Pastor and a friend, Tyran Marshall, traveled by private airplane to Miami, Florida, to meet with investors about city developments. Pastor didn't pay for or disclose that trip as required by state ethics laws.

Some of what happened in Florida is summarized in documents connected to his plea agreement.

At a Sept. 27, 2018, meeting in Miami with an undercover FBI agent posing as a developer, Pastor agreed to vote in favor of two projects in exchange for $15,000.

Pastor told the undercover agent that a nonprofit created by Marshall would "sanitize" the money.

That same day, after flying back to Cincinnati, Pastor called the undercover agent "to negotiate a monthly retainer."

Between September and November 2018, according to court documents, he received $35,000 from the undercover agent.

It apparently wasn't enough.

'I would like to be compensated for my time'

Court documents say that in January 2019, Pastor asked the unnamed developer for a $115,000 salary as well as an $85,000 salary for Marshall. The money, Pastor said, would “get the best” out of him, according to the documents. His request was rejected.

A month later, in February 2019, the documents say Pastor met with a cooperating witness, explained the steps he was taking to help with a development project and asked for an additional $25,000. The project was the redevelopment of 435 Elm St., a since-demolished property that for years has sat unused.

“I would like to be compensated for my time,” Pastor said, according to the documents.

He added that the money he previously had received "doesn't dignify the work that I am doing."

The documents say Pastor suggested that he also wanted a small percentage on the deal.

David Niven, a political science professor at the University of Cincinnati who follows local politics, said Pastor came to the job not knowing anything about city politics or how to navigate the political landscape that would involve a billion-dollar budget and a constant stream of multi-million-dollar developments.

Councilmembers rub elbows with the city's wealthiest business people and developers who come to City Hall looking for taxpayer help on projects.

"The best-case scenario was he could have grown into the role of councilman," Niven said. "The old phrase is, ‘Power doesn’t build character, it reveals character.’”

A 3-year court case

Pastor's case dragged on for three years. There were delays related to the COVID-19 pandemic and at one point his attorney was disbarred, which resulted in Pastor working with a public defender.

Pastor did not respond to text messages seeking comment for this story. His public defender did not respond to an email seeking comment.

At his sentencing in December, he told the judge that he regrets what he did and apologized to the city and taxpayers.

“There is no one else to blame. I stand here for myself," he said.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Jeff Pastor's bizarre Ohio political career ends in prison