How Democratic Party insiders could make a comeback at the 2020 convention

Democrats last year moved to restrict the role of party insiders, known as superdelegates, in presidential primaries in the hopes of convincing voters to put more trust in the party, but the size and structure of the 2020 primary now threatens to undermine that plan.

“We have to move forward … to ensure that we’re continuing that ongoing process of rebuilding trust, making sure that everything we do day in and day out as Democrats is designed to ensure that everybody’s got a fair shake,” Tom Perez, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, said a year ago as the organization’s rules committee worked through the process of reducing the superdelegates’ role.

But as the 2020 election has started to come into focus, some observers have sounded the alarm that the superdelegate loophole — which gives them a vote at the convention if the party has not settled on a nominee — may come into play this election, further sowing outrage and distrust of the DNC, the exact opposite of what was intended.

Superdelegates “could be more influential than ever if the Democratic primary devolves into a floor fight,” Dave Wasserman, of the Cook Political Report, wrote recently in the New York Times. “And the potential for back-room deal-making or heavy-handed Democratic National Committee refereeing could only further fuel grass-roots suspicion that the party’s elites are running the show, setting ablaze the prospect of party unity.”

Superdelegates are DNC members, elected members of Congress and others, who are free to support whomever they want in the party primary. After supporters of Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., decried the perceived influence of superdelegates on the 2016 primary, the DNC made changes in an attempt to heal wounds opened by the fractious battle between Sanders and the Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton.

But there were not enough votes among the DNC’s membership to completely eliminate superdelegates, and so the compromise agreement reached last August barred them from voting at the convention on the first ballot. That means if the primary process in 2020 produces a consensus candidate who has a majority of delegates heading into the convention in Milwaukee in mid-July, then superdelegates will play no role.

However, if there are two, three or even four Democrats who all win significant victories in the primaries and are all determined to stay in the primary into the convention, then there might not be a nominee after the first vote of the convention delegates. And on the second ballot, the superdelegates’ votes would then be counted, setting off a potentially chaotic sprint to win their support.

There are currently 3,768 pledged delegates whose votes will count on the first ballot. There are 764 superdelegates, also known as unpledged delegates, who in a contested convention would suddenly represent one-fifth of the entire delegate total.

For those who pushed for reform, the prospects of superdelegates determining the candidate in a contested convention would look like a bait and switch. The DNC reforms were done in the name of increasing fairness and democracy, but a superdelegate process would come across to many as an insider-driven decision.

But some DNC veterans who know the primary process well said they don’t believe the Democratic primary will result in a deadlocked convention. And, some added, even if it did, the superdelegates’ influence would be welcomed rather than decried.

“I just don’t see it happening,” said Kathleen Sullivan, a DNC member from New Hampshire.

Florida consultant Steve Schale, an ally of former Vice President Joe Biden — a possible 2020 contender — agreed that a deadlock is unlikely. “I think it’s a long shot,” he said.

“When you look at the number of candidates, it’s possible … but it’s unlikely,” said Larry Cohen, chairman of the board at Our Revolution, a group that supports Sen. Bernie Sanders’s candidacy.

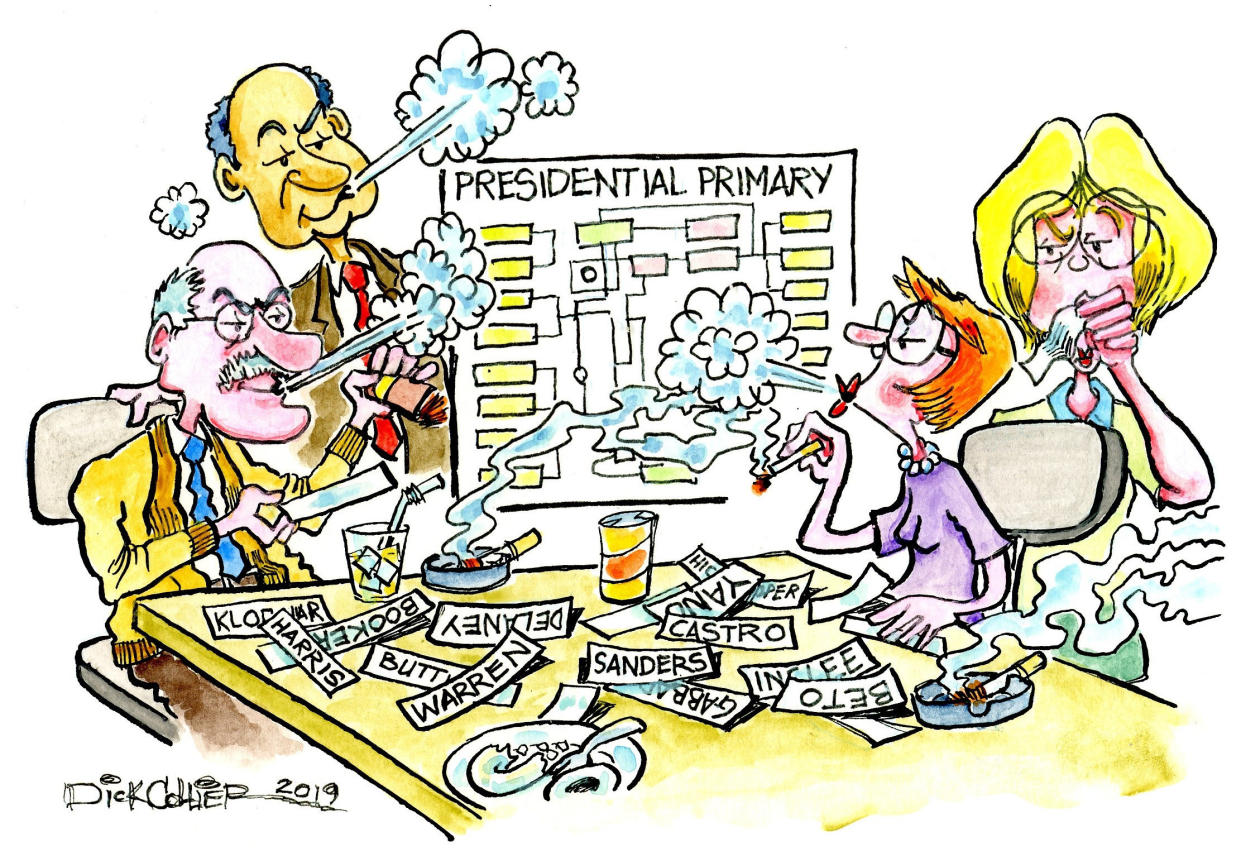

Elaine Kamarck, an at-large DNC member who is one of the party’s foremost rules experts, was one of several who argued that the primary process will winnow the current field long before the convention approaches. There are currently 15 declared candidates in the Democratic field, with Biden and a handful of others threatening to push the final number above 20.

Kamarck and others also argued that if the primary result was not conclusive, the public would welcome the superdelegates’ role.

“There’s a source of legitimacy to say, look, the voters didn’t decide. And if the voters didn’t decide, you can’t rerun 50 elections,” Kamarck told Yahoo News. “The natural people to decide are the leadership of the party, and that would be the superdelegates. I think there’s a legitimacy that people would be willing to accord it.”

Perhaps a bit surprisingly, Cohen agreed.

“Is it great that superdelegates come in on the second ballot? I would say not, but it’s not the end of the world,” Cohen told Yahoo News. “Something has to break a deadlock.”

David McDonald, a DNC member from Washington state who is on the Rules & Bylaws committee, agreed but also said that if there were a contested convention, the handful of Democrats still in contention would know “that if they do not work out something between themselves, the superdelegates will vote on the next round.” That, he said, could be a powerful incentive to reach a compromise.

But McDonald said that if no agreement could be reached among the primary candidates, the superdelegates could conceivably produce a nominee who had not even run in the primary.

“Were the superdelegates on the second round to facilitate a wholly new unity candidate, I believe the public would like it better than the alternative the pledged delegates had arrived at,” McDonald told Yahoo News.

This is what happened at the 1952 convention, when Democrats chose Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson, who went on to lose in a landslide to Dwight Eisenhower.

McDonald argued that choosing one of the candidates from within a group who were splitting the vote three or four ways would be divisive, and choosing someone from outside that group as a “unity candidate” could be a solution.

But the idea that Bernie supporters, for example, would be OK with superdelegates picking some new person as the nominee in the event of a three- or four-way tie is far-fetched, said Cohen, the Sanders supporter.

“I don’t see it,” Cohen said. “I don’t think that would be popular. … Unless there is some legitimate reason, like health, I don’t think people are going to accept a candidate they had nothing to do with.”

Cohen also said there is a “legitimate concern” about the sudden reemergence of superdelegates on a second ballot, but the argument he and others would make is that all delegates become unpledged on the second ballot.

“If everybody’s unpledged, why is the wisdom of someone who ran as a delegate for X any better than the wisdom of a state party chair?” Cohen said.

Democrats, of course, hope that it doesn’t come to this, but that may be wishful thinking. In particular, the Democratic primary is governed by “strict proportionality,” said at-large DNC member Jeff Berman, another top rules expert in the party. That means no candidate can sweep up the majority of a state’s delegates simply by winning the largest percentage of the primary, as happens in the Republican primary.

In 2016, for example, Donald Trump won all or most of the delegates in many states while garnering only 30 or 40 percent of the vote. In the Democratic primary, a candidate with a third of the primary vote would get a third of the delegates in that state, generally speaking, and the candidates who finished with lower percentages would receive delegates corresponding to their percentage of the vote, with one big caveat: Candidates have to receive more than 15 percent of the vote to receive any delegates.

The 15 percent threshold is a significant winnowing factor that will narrow the field. But the strict proportionality still means that there is greater potential for multiple candidates to win delegates in multiple states and to argue that they are credible contenders. This is especially the case since at least a third of all the delegates, and possibly as much as nearly half of them, will be awarded in the first month of the primary.

Schale argued that the first two contests — Iowa and New Hampshire — will play an outsize role. “Not that Iowa and New Hampshire don’t mean a lot every time, but given the fact that the field is so big, I think in a lot of ways they will really narrow the field. You spend yourself to broke to get through those first few states, and if you finish ninth in Iowa, I don’t know what the argument is to keep going,” Schale said.

But as Wasserman pointed out, the contest will quickly move after Nevada and South Carolina to Super Tuesday on March 3, when massive numbers of delegates will be the prize. California has moved its primary up to that day and will award 416 delegates, as has Texas, where there are 228.

The Democrats’ other hope of avoiding an ugly contested convention is that their voters act pragmatically and look for a consensus candidate to unify around.

“I just think the importance of defeating Trump will keep them from pursuing sort of lost causes,” Kamarck said.

If things do head toward a contested convention despite all that, there’s always “old-fashioned bargaining,” Kamarck said. “The first way to do this would be to bargain for the vice presidency,” she said.

And if the voters do not unify behind one candidate, and the handful of candidates still standing at the end can’t work out a compromise, then Democrats are prepared to absorb some complaining about a superdelegate-driven result.

“It’s not like we did this in secret. It’s been established since last year,” Kamarck said. “People will complain and then it will be pointed out to them that this was always the case.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: