Detroit buildings were headed for demolition. Then a savior stepped in.

A once-grand building in Detroit grows old and empties out.

Renovations are sorely needed, but the business case seems weak.

Some suggest the most practical option — maybe the only option — is to demolish the building and start fresh.

This type of sequence famously played out for Michigan Central Station, the 1913 Beaux Arts train depot in the city's Corktown neighborhood that stayed vacant and blighted for decades after Amtrak pulled out.

But the depot also serves as an object lesson in how patience can sometimes be a virtue when determining the next step — rehab or demo — for aging landmark buildings that suddenly lack occupants and a clear future path.

Had a 2009 demolition effort by Detroit City Council succeeded, Michigan Central Station wouldn't have survived long enough for its eventual savior to appear, a savior with the motivation and the money to pull off one of the most dramatic historical renovations in the country.

That rehab effort by Ford Motor Co. — universally acclaimed and recently completed — may well have given the old depot another century of existence, this time with a different mix of uses and building occupants.

The experience could be instructive for those tasked with determining the next act for downtown's Renaissance Center after General Motors moves out next year.

GM CEO Mary Barra didn't rule out demolition of the landmark complex when speaking this spring before the Detroit Economic Club. GM still owns the property and is brainstorming with Dan Gilbert's Bedrock real estate firm on what to do next with the RenCen, including possible office-to-housing conversions.

Below are some other Detroit buildings that at one time were thought to be beyond saving, but after the passage of years or even decades, the situation changed and developers stepped forward.

Book Cadillac and Fort Shelby rebirths

The Book Cadillac hotel, 1114 Washington Blvd., opened in 1924 and reigned for decades as one of Detroit's most renowned hotels, hosting celebrities, sports stars and politicians including John F. Kennedy. But the hotel declined as the city did in the 1970s and eventually went bankrupt and closed in 1984.

The 34-story hotel remained closed for more than two decades. Through the efforts of then-Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick and Detroit development officials, a complex deal was eventually put together with a Cleveland developer that rehabbed and reopened the Book Cadillac in fall 2008 with luxury hotel rooms and high-end condos.

“There was a lot of hand wringing about the Book Cadillac for years; a lot of people were calling for tearing it down," said Michael Boettcher, an urban planner and historic Detroit tour guide. "But there were some intrepid, talented people who put a deal together.”

Weeks after the 453-room Westin Book Cadillac had its reopening, another long-vacant downtown hotel that was once in even worse physical condition made its second debut.

The 22-story Fort Shelby Hotel, 525 W. Lafayette Blvd., is an Albert Kahn-designed building that opened in 1916. It closed in the 1970s and fell into extreme disrepair, with trees growing through its roof.

The building was once thought to be beyond saving and another candidate for demolition, until metro Detroit real estate investors Emmett Moten, Leo Phillips and others teamed up with DoubleTree to restore it. It reopened in December 2008 as a DoubleTree Suites by Hilton Hotel featuring 203 guest rooms, plus 56 residences on the upper floors.

Hotel Eddystone

A decade ago, there were two abandoned hotels near the footprint of what is now Little Caesars Arena.

One was the old 13-story Hotel Eddystone, the other was the 13-story Park Avenue Hotel. The hotels dated to 1924 and 1925, respectively, and each were on the National Register of Historic Places.

Each lacked windows at the time, leaving them open to the elements and sped up physical decay. Their fate was the subject of negotiations between city officials and the Ilitch organization's Olympia Development of Michigan, which was preparing to build LCA as the successor to Joe Louis Arena.

The negotiations resulted in a compromise that allowed for demolition of the Park Avenue Hotel, but the preservation and redevelopment of the Eddystone. After some starts and stops, the Eddystone underwent an extensive rehab and reopened in late 2021 as upscale housing, most of it market-rate although 20% reserved as affordable.

Book Depository

Situated next door to Michigan Central Station, the old Book Depository building opened in 1936 as a U.S. Post Office and later was a warehouse for Detroit Public Schools. The district stopped using the three-story, 270,000-square-foot building after a 1987 fire that severely damaged the interior.

It sat unused for about 30 years until Ford also bought it in 2018 from the Moroun family.

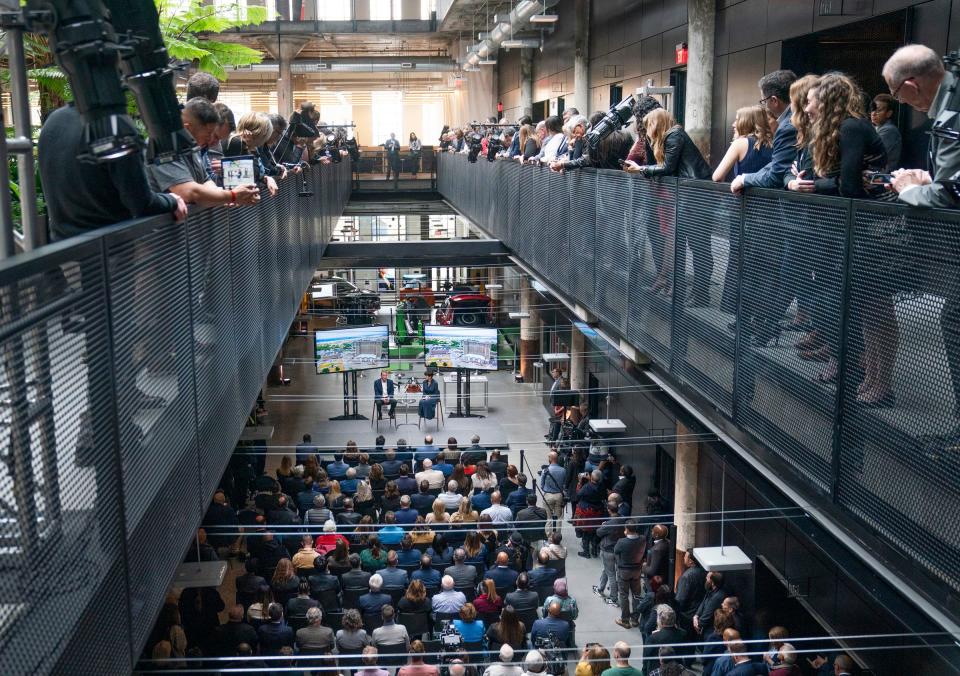

The building reopened last year as the Newlab at Michigan Central Building with modern workspaces and studios for mobility-focused companies and technologies.

Wheeler Recreation Center

Some projects are still works in progress.

The old Brewster Wheeler Recreation Center in the city's Brush Park neighborhood dates to 1929 and is where Joe Louis once trained and generations of Detroiters learned to swim. It is adjacent to the since-demolished Brewster-Douglass public housing projects.

The rec center closed in the early 2000s and fell prey to graffiti and trespassers. In 2014, the city added the building to its demolition list, saying it would come down that fall unless someone presented "a workable redevelopment plan."

Soon after, developers stepped forward with a vision to rehab the rec center into events space and a restaurant with a rooftop beer garden. But the plan faltered and the building stayed empty.

Then last fall a new plan emerged, this one calling for a fully renovation of the rec center building as a community fitness center. The nonprofit developer behind the plan, MHT Housing, also gained approval to build over 200 units of nearby affordable housing.

While the developer didn't respond to Free Press inquiries this week regarding the status of the rec center rehab, the building appears to be an active construction site.

Fisher Body Plant

The old Fisher Body Plant No. 21, located at 6051 Hastings St. near Interstate 75 and I-94, opened in 1919 and initially made auto bodies for Cadillacs and Buicks. The massive six-story, 600,000-square-foot building has been empty since 1993 and owned by the city since 2000.

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan was leaning toward demolishing the empty factory building until local developers Gregory Jackson and Richard Hosey stepped forward in early 2022 with an ambitious redevelopment plan: converting the structure into 433 apartments, plus retail and co-working space.

The industrial-to-residential conversion project, known as Fisher 21 Lofts, has already undergone a Community Benefits process and gained approvals for a medley of development incentives, including tax credits, tax breaks and a Brownfield tax capture.

A project representative couldn't be reached this week, but recently told Crain's Detroit that construction work could begin after their financing closes, which is expected in September.

A post-demolition success

To be sure, saving old buildings may not always be the highest and best option for development.

There was an organized effort in the 1990s to save and repurpose the massive J.L. Hudson department store building on Woodward in downtown. But demolitionists prevailed over the preservationists, and the 2.1 million-square-foot building was imploded in October 1998.

A quarter century later, the Hudson's site is home to two all-new buildings that are reshaping Detroit's skyline and generating excitement: a 12-story office building and a 45-floor skyscraper — the second tallest in downtown — with luxury hotel rooms and condos. The buildings, developed by Gilbert's Bedrock, are gradually nearing completion and have already gained national attention.

While this outcome appears to be a win for Detroit, Boettcher, the urban planner and historic tour guide, noted how the site of the former department store wasn't the only vacant parcel in downtown.

So Gilbert conceivably could have still done his celebrated new developments, even if the J.L. Hudson building remained standing today.

“In the case of Hudson’s (demolition), whether or not that’s was the right idea is debatable," Boettcher said. "It is entirely possible that that building could have been rehabbed. And if it was, somebody like Gilbert would have found another site. So I don’t think it’s a matter of one or the other only."

More: It wasn't just the Morouns who let Michigan Central Station slide into decay

Contact JC Reindl: 313-378-5460 or jcreindl@freepress.com. Follow him on X @jcreindl.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit buildings were headed for demolition until they were saved