PHOTOS: #MenToo: The hidden tragedy of male sexual abuse in the military

Award-winning photojournalist Mary F. Calvert has spent six years documenting the prevalence of rape in the military and the effects on victims. She began with a focus on female victims but more recently has examined the underreported incidence of sexual assaults on men and the lifelong trauma it can inflict.

_____

Last March, Sen. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., a retired Air Force combat pilot, disclosed that she had been the victim of multiple sexual assaults by fellow officers, putting the issue of sexual assault in the military on the national agenda. Two months later, a required biannual Department of Defense report found that sexual assault within the ranks had increased by 38 percent over two years. Much less attention has been given to the problem of sexual assault against men in uniform. The report estimated that “20,500 Service members, representing about 13,000 women and 7,500 men, experienced some kind of contact or penetrative sexual assault in 2018, up from approximately 14,900 in 2016.”

Although the military has made efforts to encourage victims to come forward, most assaults are still not reported, and victims who do make reports sometimes still face retaliation. Although men are less likely to be victimized than women, the stigma and psychological trauma can be equally devastating. A DOD report released on Nov. 5 determined that military sexual assault might be more likely to cause PTSD than combat.

“Male victims of sexual assault in [the military] remain in the shadows and are not receiving the care and support they need,” said retired Marine Corps Col. Scott Jensen, the vice chair of Protect Our Defenders, an organization that combats military rape and assault. “When it comes to actual reporting of sexual assaults, it is telling that male victims actually file a report at such a low rate [18 percent] when we know from DOD’s own 2016 survey that 42 percent of overall victims are male. A system that addresses men and women in the same way without sensitivity to the nuances and differences between survivors of different genders is destined to fail. Much more attention to both preventing and responding to male survivors is necessary to ensure that those who are suffering feel comfortable and supported enough to report.

“This can only happen when a cultural shift occurs that reduces the stigma of reporting a sexual assault in a hypermasculine culture. That type of change will not occur without focused, aggressive and demanding leadership on the part of the leadership of DOD.”

The effects of military sexual trauma (MST) in male victims include depression, substance abuse, paranoia, hypervigilance, anger and feelings of isolation. Victims may turn to alcohol or drugs or end up homeless, even suicidal.

There are few treatment programs in the U.S. military for male MST victims. Most men are lumped in with combat PTSD sufferers, who often resent the presence of rape victims and treat them as phonies and pariahs. The Department of Veterans Affairs has few beds reserved for MST victims nationwide, and most are assigned to women.

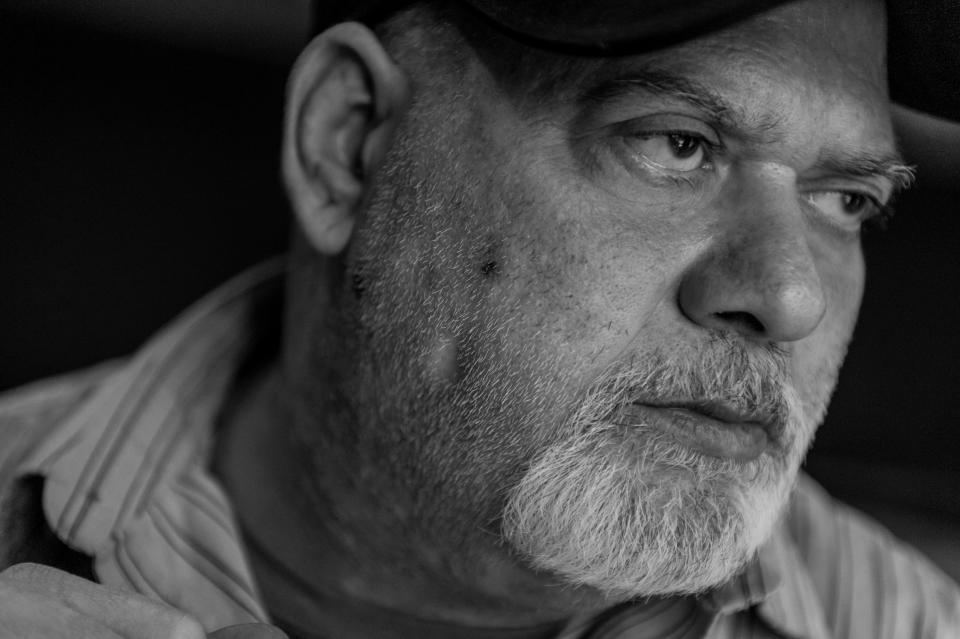

Here are a few of the male victims’ stories:

Jack Williams

Jack Williams, 72, spends the night at a highway rest stop in Everett, Wash. Williams was raped by an instructor when he served in the U.S. Air Force in 1966. He reported the rape immediately but the response by his superiors was to threaten him with a homosexual discharge. “Back in 1966 if you admitted you'd been raped that was the same as saying you were a child molester,” he says. “My PTSD has been so bad for all these years. ... All those years I have not been able to sleep in a normal way like normal people do. I have to carry extra clothes with me because I soil myself. ... I feel that the government should have to bear the expense of repairing me even though I am old.”

Ethan Hanson

Six years after he was sexually hazed in a shower during Marine boot camp, Ethan Hanson still can’t shower, even at home. The assault, he says, was punishment by his drill instructor for talking and laughing with other recruits in the shower. “When I come into contact with steam, hot water, anything that makes my skin slippery, it's back to being in that shower again. ... It makes me want to vomit up every bit of bile I have.”

Paul Lloyd

Ten years ago, Paul Lloyd was raped by a fellow soldier in the shower during Army boot camp. After the attack he spent 14 days in the hospital but never reported the crime. A few months later he was given a general discharge from and went home to Salt Lake City to try to rebuild his life. He was comforted by his wife, Rachel, after a flashback in the grocery store.

“We were at the store. I was looking at some stuff and started smelling some candles and found a candle that triggered me back into a flashback. It's similar to the scent of the shampoo I was using at the time of the assault. When it happens, you're back there; you're back in that little three-by-three-square shower, cold tile and hot water and cold water running down. You do, you feel psychologically, not just physiologically, your mind goes back to the pain at the time of the assault being thrown up against the wall multiple times, being forced to do things, forced having your jaw open. It's hell, and there's no escape from it,” he said.

To escape the nightmares that follow his flashbacks, Lloyd sometimes stays up late doing chores like cleaning the house. “The flashbacks keep me from sleeping and so I clean, I over clean, I’m obsessed because I have to get my mind off of what had happened. I think the worst I've ever gotten is four days without sleeping, like an actual good night's rest or even just a decent rest. I just obsess. It’s something that I have complete control over when I clean and that’s why I do it.”

Billy Joe Capshaw

Billy Joe Capshaw was 17 years old when he joined the U.S. Army to help support his family in Hot Springs, Ark. His mother signed for him and he was shipped off to Germany where he spent the next 18 months being raped and tortured by his roommate — the notorious serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, who after his discharge committed at least 17 murders, dismembering and in some cases eating the victims. (Dahmer was killed in prison by another inmate in 1994.) Capshaw reported the abuse, but, he says, the Army did nothing to protect him. At one point he jumped out of a third-story window to get away from his rapist but was literally dragged back into the room. Dahmer was eventually discharged for alcohol abuse. Soon after, Capshaw was given an honorable discharge and sent home, where he stayed in his room for five years.

“I had to get 26 years of therapy because of this. I look like a leopard. I got spots all over me, I mean, just horrible scars and it’s just ruined my life. And just being attached to the name of Jeffrey Dahmer, I can never hold a job.”

Capshaw stays up late drinking and watching music videos on his computer. The kitchen light is always on. “When I first got to Germany I was 17 years old and I think it was in February when I got there, in 1979 or 1980,” said Capshaw. “I met Jeff and we became roommates. I think the first or second night he started acting funny and by the third night I’d been raped and I didn’t know what to do, I really didn’t. I didn’t know who to go to or any of that stuff. He was drinking heavy and I told him what happened the next morning. He just looked at me like, ‘Who cares?’ Kind of a blank look.”

Capshaw sleeps on his living room couch with the kitchen light on. He says he cannot sleep in a dark room or a bed because he was raped in a bed. “If you knew how hard it is to admit your rape,” he says. “I’m getting stuck for words. It’s hard to admit. Wow. If you’re a man, it’s very hard to admit you get raped. It takes away from everything you were ever, ever, ever told in life by your mother, your father, everything. It takes away your sexuality; it takes away from you emotionally. You’re vulnerable in a lot of ways.

“You feel that way all the time. We feel like somebody knows it that’s the only way to get better is to admit it. I mean tell people and now there’s not such a stigma about it because it’s been going on so long.”

Text and photography by Mary F. Calvert

Jerry Adler/Yahoo News contributed to this report

See more news-related photo galleries and follow us on Yahoo News Photo Twitter.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: