Preliminary survey shows impact of summer heatwave on coral in the Florida Keys

A preliminary assessment of the impact of an underwater summer heatwave on seven iconic sites on the Florida Reef Tract Feb. 14 initially paints a bleak picture of damage.

For example, five of the seven sites targeted for restoration by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-led Mission: Iconic Reefs were surveyed and only 22% of 1,500 specimens of staghorn coral previously planted by scientists remained alive – all in the Upper Keys.

Still, data from the mission will help NOAA and its research partners understand the extent of the impact of record-high marine temperatures from the summer of 2023 on those restored corals – which are nursery-raised and planted on the reef.

It will also help form future restoration strategies to increase coral resilience.

“The findings from this assessment are critical to understanding the impacts to corals throughout the Florida Keys following the unprecedented marine heat wave,” Sarah Fangman, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary superintendent, said in a prepared statement. “They also offer a glimpse into coral’s future in a warming world. When the ecosystem experiences significant stress in this way, it underscores the urgency for implementing updates to our regulations, like the Restoration Blueprint, which addresses multiple threats that will give nature a chance to hold on.”

All the corals surveyed were tagged and previously planted by scientists and left out for the duration of the high temperature event.

Staghorn and elkhorn coral were particularly impacted by warm water and subsequent bleaching in a historic climate event that drew international attention after an underwater sensor in Florida Bay recorded a temperature of 101.5 degrees on July 24.

Tens of thousands of heat-stressed corals were rescued from underwater nurseries in an effort that was frequently compared to Noah’s Ark, and safeguarded in land-based coral nurseries and aquariums subsequently returned once the water cooled.

What does the preliminary data indicate?

Preliminary data showed that less than 22% of approximately 1,500 staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) surveyed remain alive – all of those were located on the two most northern reefs surveyed, Carysfort Reef and Horseshoe Reef.

No live staghorn or elkhorn corals were observed at sample areas surveyed at Looe Key Reef in the lower Florida Keys.

Of the five reefs surveyed, live elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) was found at only three sites: Carysfort Reef, Sombrero Reef in the Middle Keys, and Eastern Dry Rocks off Key West.

Anecdotal evidence from Mission: Iconic Reefs partners suggest that boulder, massive and brain coral outplants at a number of sites – including Looe Key Reef – fared better during the marine heat wave.

Rough weather conditions during this mission prevented the research team from surveying more than the branching coral assemblages of staghorn and elkhorn coral.

All data collected during the assessment is currently undergoing review and analysis.

Dr. Erinn Muller, program manager for coral health & disease and senior scientist at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium, noted that staghorn and elkhorn corals are more sensitive to bleaching and die more quickly after a bleaching event.

“You see them bleach and they either quickly succumb to bleaching or disease – we often see disease come as a one-two punch after bleaching occurs,” Muller said.

The positive results for the massive boulder and brain corals – critical for reef-building – are encouraging, but those corals react differently to heat stress than staghorn and elkhorn, Muller said.

“With the boulder and brain corals, they can survive bleaching or being bleached for much longer periods of time, so in many ways their story is yet to be told,” Muller said.

“We’re going to be focusing on that for the next six months,” she added. “We’re still watching them slowly recover; they could still succumb to disease, so we want to make sure we don’t monitor them too early and miss the story.”

How was the survey conducted?

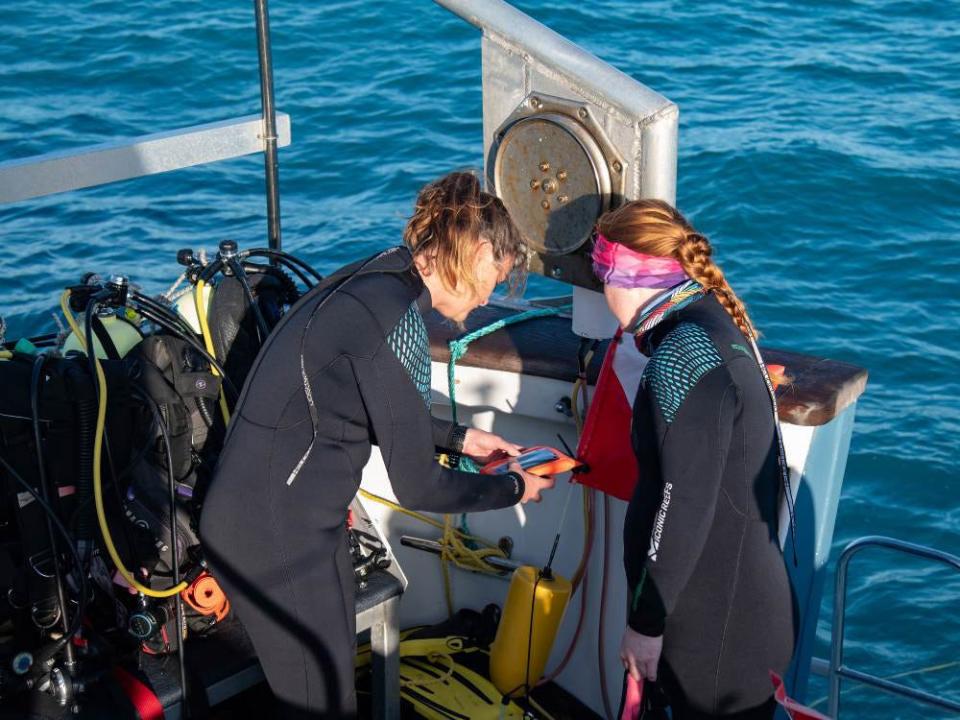

Researchers aboard the contracted vessel M/V Makai surveyed 64 locations at five of the seven Mission: Iconic Reef sites – Carysfort Reef, Horseshoe Reef, Sombrero Reef, Looe Key Reef, and Eastern Dry Rocks – to examine the reef-building stony acroporid corals planted by the Coral Restoration Foundation, Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium and Reef Renewal.

The research was a follow up on a mission in August that assessed coral health during the height of the marine heat wave and incorporates data about how eight additional weeks of high temperatures affected corals.

Those nurseries are key to Mission Iconic Reefs, a $100-million effort by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and seven partners to restore roughly 3 million square feet of coral reefs on seven iconic sites along the 300-plus mile long Florida Reef Tract.

NOAA projects the value of the reef along southeast Florida at $8.5 billion, with more than 70,000 full and part-time jobs generated.

Other preliminary success stories

The fact that elkhorn coral survived on the Mission: Iconic Reef sites bodes well for the effort of scientists to cross-breed corals to promote genetic traits that would allow them to survive high temperatures, disease or other issues that have plagued the reef.

Muller said that, as far as she knew, Mote is the only one of the partners in Mission: Iconic Reefs that has planted those corals.

“Anything south from the Upper Keys, the only living elkhorn corals out there are our sexually produced out-plants,” Muller said. “All evidence suggests that the wild elkhorn corals are gone and the only corals that do remain are the corals that we put out there as sexual recruits.”

And while no staghorn coral survived in the southern Mission: Iconic Reefs sites, Muller said staghorn corals cross-bred for resiliency and out-planted by Mote at other reef sites have survived the summer underwater heatwave.

“A lot of the surviving staghorn coral in the Lower Keys – where the water temperatures were the hottest – those survivors are primarily sexual recruits of staghorn coral as well,” Muller said, while citing the efforts over the past six years by Dr. Hannah Koch, the staff scientist who specializes in coral reproduction.

Muller said the fact that those corals survived the heatwave, “In a very dramatic way, points to the years that we put into developing assisted sexual production with corals and a lot of our resilience work with them.”

Similar surveys and studies of the surviving boulder and brain corals are planned.

Muller said it will be important to learn about “this almost miraculously high survival rate of a lot of our boulder and brain corals that live in some of the warmest water temperatures in any year and more so this year.

“Those corals we put out there, a lot of those individuals survived and are obviously recovering,” she added. “It’s phenomenal to be able to see those pathways forward that we can continue to integrate and do more informed restoration.”

What happens if another underwater heat wave occurs in 2024?

Muller said that coral scientists have been examing other ways to safeguard corals in underwater coral nurseries – including moving them to nursery sites in deeper water.

Related: World's largest deep-sea coral reef mapped 100 miles off coast of Florida. How big is it?

“It’s a much more efficient process and can reduce the stress by reducing the light,” she said, adding that the infrastructure is already in place to move corals back onto land if needed.

Jennifer Moore, co-lead of Mission: Iconic Reefs and Endangered Species Act coral recovery coordinator for NOAA Fisheries, noted that the collaborative efforts of multiple partners will be key in developing “effective and innovative restoration strategies to support the health of Florida’s coral reefs.”

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: NOAA-led coral survey documents impact of underwater heatwave in Keys