Sarasota's Mote biologists care for coral rescued from July heatwave in the Florida Keys

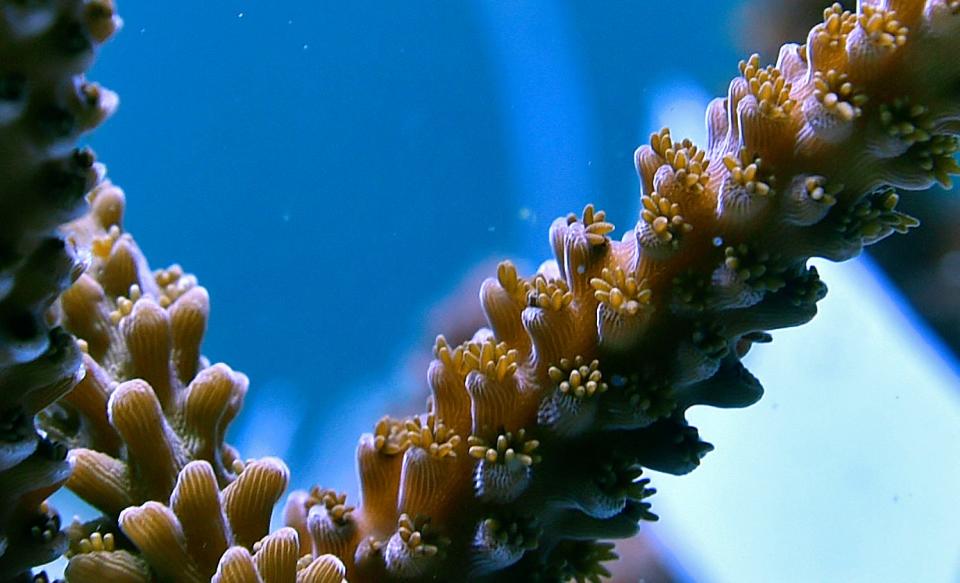

Marine biologist Lauren Burk leaned down and squeezed out several ounces of a nutritious soup of amino acids, phytoplankton and brine shrimp from a pipette into a kiddie-pool size tub filled with two dozen fragments of Staghorn coral.

It was feeding time at the Mote Aquaculture Research Park for corals rescued after a mid-July wave of warm water in the Florida Keys triggered a mass bleaching event.

They arrived with more than 2,000 other Staghorn and Elkhorn corals evacuated from nurseries designed to produce coral to repopulate the Florida Reef Tract.

Corals are colonies of tiny polyps that eat plankton. They live in a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae algae, which feed on coral waste and carbon dioxide and provide the coral oxygen and organic products of photosynthesis.

Those two dozen corals have recently taken up residence in a 20,000-gallon tank in Mote’s Florida Coral Reef Restoration Crab Hatchery Research Center, along with a host of other Staghorn coral.

On a recent Tuesday, Burk, along with Kari Imhof, a marine biologist with Mote’s coral health and disease program, and research technician Chloe Manley, were tasked with feeding all the corals in that 20,000-gallon tank, a process that included Imhof getting in the tank and removing a rack of corals transferred to that tub for feeding.

The corals spend about a half hour in the mini pool filled with sea water and essentially being hand-fed by Burk.

“That gives them time to do a full polyp extension and grab what’s floating around,” Imhoff said.

“In the ocean, in the wild, they have a lot of different things swimming around – microplankton, shrimp – when they’re in captivity like this, it’s important we introduce new nutrients.”

Dr. Erinn Muller, program manager for coral health & disease and senior scientist at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium, said every rescued coral gets treated that way.

“We feed them at least once a week but we try to do it twice a week,” Muller said.

Saving unique genotypes

Mote houses about 250 unique Staghorn coral genotypes and 150 Elkhorn coral genotypes rescued from the underwater heat wave. A similar stockpile of coral is also housed at The Reef Institute, a coral research and restoration facility in West Palm Beach.

Staghorn and Elkhorn coral were particularly impacted by warm water and subsequent bleaching in a historic climate event that garnered international attention after an underwater sensor in Florida Bay recorded a temperature of 101.5 degrees on July 24.

By then though, coral scientists in the Florida Keys were already involved in an effort to get a variety of endangered corals out of the underwater nurseries and away from the bleaching danger.

Those nurseries are key to Mission Iconic Reefs, a $100-million effort by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and seven partners to restore roughly 3 million square feet of coral reefs on seven iconic sites along the 300-plus mile long Florida Reef Tract.

Muller said the effort includes both Staghorn and Elkhorn genotypes, representing different colonies with different genetic combinations both to Mote’s gene bank and the Reef Institute.

“For these particular species, those genotypes that are in the nurseries, for the most part they’re the only ones that exist in Florida anymore,” Muller said.

She noted that while many of the rescued corals will be returned to the Keys when the water cools – likely around November – others will be retained in gene banks to spawn.

“They’re the ones that you are using to bring back that population from potential extinction,” Muller added, aiming to "increase the diversity of the species.

“The idea is to keep them there in the real, living Noah’s Ark of the species.”

A mission of resiliency

As part of Mission Iconic Reefs, scientists are working to develop corals that will be resilient to warming oceans, ocean acidification – caused by increased levels of carbon dioxide – disease and other factors.

Healthy corals that retain their zooxanthellae algae create calcium carbonate, or limestone, which makes up a coral reef. Coral reefs provide habitat for almost 25% of life in the ocean and protection from storms for homes along the coast.

NOAA projects the value of the reef along southeast Florida at $8.5 billion, with more than 70,000 full and part-time jobs generated.

Once resilient corals are identified, the technique of micro-fragmentation, a process that capitalizes on the natural healing process and allows corals to grow more than 25 times faster than normal – with some larger boulder corals growing up to 50 times faster – can be used to fast-track their growth.

Those corals would be planted at seven iconic sites – the Carysfort Reef Complex and Horseshoe Reef in the upper keys; Cheeca Rocks and Sombrero Key in the middle keys; and Looe Key, Newfound Harbor Patches and Eastern Dry Docks in the lower keys.

That would increase cover on those sites from an estimated 2% prior to the current bleaching event, which started in July, to 25% by 2035.

Mote is working to restore three additional reefs: American Shoal offshore between Sugarloaf Key and the Saddlebunch Keys; Coffin’s Patch, a shallow reef southeast of Bamboo Key near Marathon, and Ham Reef off of Islamorada.

A shared effort

Though Hurricane Idalia both bumped the coral bleaching crisis from the headlines and cooled the temperature as much as two degrees (according to a social media post from the Coral Restoration Foundation) scientists are still transporting corals from offshore nurseries to safe havens such as Mote and the Reef Institute, as well as the Florida Aquarium conservation campus Apollo Beach, the Florida Coral Rescue Center in Orlando, Mote Aquaculture Park and facilities at the University of Miami and Nova Southeastern University.

Muller noted that Mote is expecting another shipment later this month.

In years past, water temperatures would not hit the critical 88-90 degree range that could prompt a bleaching event until late August or September.

As part of a sharing program corals from several institutions that work in the Keys are being stored in the different land-based aquariums.

Each batch of coral is quarantined in its own tank.

Several coral tanks – including those that first arrived at the 200-acre Mote Aquaculture Research Park off of Fruitville Road – are housed in Mote’s Florida Red Tide Mitigation & Technology Development Facility.

One Staghorn quarantine tank contains fragments with tags from Mote as well as from partner organizations such as the University of Miami, Nova Southeastern and the Reef Institute.

A neighboring tank contained severely bleached Elkhorn coral from Biscayne National Park that is also being treated with antibiotics.

Mote’s Coral Gene Bank – one of the largest of its type in the world – even has a temporary annex in another room at the red tide center, as well as the corals in large crab research center tanks.

Complicating things further is that each tank at MAP has a self-contained water circulation system for safety.

“These corals, they’ve been through a lot,” Muller said. “They were in really warm water temperatures for at least one to two months before we got them and then we had to make the trek up here.

“It’s a lot of hand-holding to make sure the corals stay healthy,” she added. “The ones we’ll see in the gene bank, they were very bleached when we got them.”

A learning opportunity

While all the rescued corals at Mote and the Reef Institute came from nurseries, other corals were left in place, so the scientists can see which genotype fares the best.

“Those are the ones I want to learn most from and figure out what makes them tick and make sure that whatever I can learn from them we can integrate across our restoration efforts more thoughtfully across our restoration efforts,” Muller said.

“Unfortunately this isn’t the last heating event,” she added. “This is going to become more and more the norm and I don’t want to move corals from our in-water nurseries to Sarasota for a few months every single year.

“We can’t move outplants back onto land every single year, so we have to make sure that whatever we’re doing for restoration has to withstand these events – and maybe those events are coming more intensely and more quickly than we envisioned but we knew they were coming – now we have to learn from it and make sure more corals survival the next event.”

While the coral community, especially in the Keys, has been close knit, efforts to combat stony coral tissue loss disease – a virus that first occurred in 2014 near Miami and eventually spread throughout the Keys – forged a heightened sense of teamwork, as did NOAA’s creation of Mission Iconic Reefs.

Muller said an unintended consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which put a damper on travel to international conferences to share techniques, was that it increased opportunities for virtual meetings and a more frequent sharing of ideas.

“Because of that it’s allowed connectivity across the globe to occur in much more real time space,” Muller said. “The good news is that there’s so much innovation within restoration right now – within Florida but also around the world – and everybody is talking .. and we’re all learning from each other because of it.”

Earlier: Mote receives nearly $7 million from NOAA to enhance Keys coral reef restoration effort

Related: Big Red (or his offspring) may one day help scientists restore iconic Florida coral reefs

Also: Caribbean king crabs arrive at Mote Aquaculture Park; seen as key to restoring coral reefs

And: What you need to know about Florida’s Coral Reef

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Mote biologists care for Elkhorn and Staghorn corals rescued from Keys