A dangerous hitchhiker: How spotted lanternflies get around

In the video, a spotted lanternfly is clinging to the hood of a car with its wings fluttering from the wind. A moment later, the wind blows the invasive bug off the car.

Experiments show the spotted lanternfly, often referred to as SLF by folks researching it, can stay on a vehicle traveling at up to about 65 mph, particularly when they are in window wells or on wipers, U.S. Department of Agriculture research entomologist Tracy Leskey said.

They also often survive if they hit a windshield on a trailing vehicle, Leskey told about 100 people attending her spotted lanternfly talk Wednesday night at the National Conservation Training Center north of Shepherdstown, W.Va. The talk was co-sponsored by the Potomac Valley Audubon Society.

The pest's ability to cling to a moving vehicle and survive being blown off are among the reasons it can spread and colonize in other areas, said Leskey, who is station director at the Appalachian Fruit Research Station in Kearneysville, W.Va. Spotted lanternflies hitchhike along major transportation corridors like Interstate 81 and rail lines.

The agriculture department and several partners continue to do research and experiments, like the wind-related ones, about the spotted lanternfly because of concerns regarding the ecological and economic harm the bug can cause. Those partners have included universities like Penn State, Virginia Tech, Rutgers and the University of Maryland, as well as Fort Detrick in Frederick County, Md. The Army base hosted a quarantine greenhouse for research about spotted lanternflies and host plants, Leskey said.

Among the plants it feeds on are grape vines, particularly wine grape vines, Leskey said. That feeding causes wilting, stunting and fungal problems.

Some vineyard owners reported yield losses up to 90% from spotted lanternfly infestation. The pests do "quite well on wine grapes" putting those particular varieties at risk, she said.

A brief history of the spotted lanternfly

The spotted lanternfly is native to China, India and Vietnam. Before arriving in the U.S. in Berks County, Pa., in 2014, it was invasive in South Korea and Japan, Leskey said.

SLF likely arrived in the U.S. via a decorated stone shipment from China, she said. Pennsylvania officials immediately put a quarantine and mitigation plan in place to stem the pest's spread and try to eradicate it.

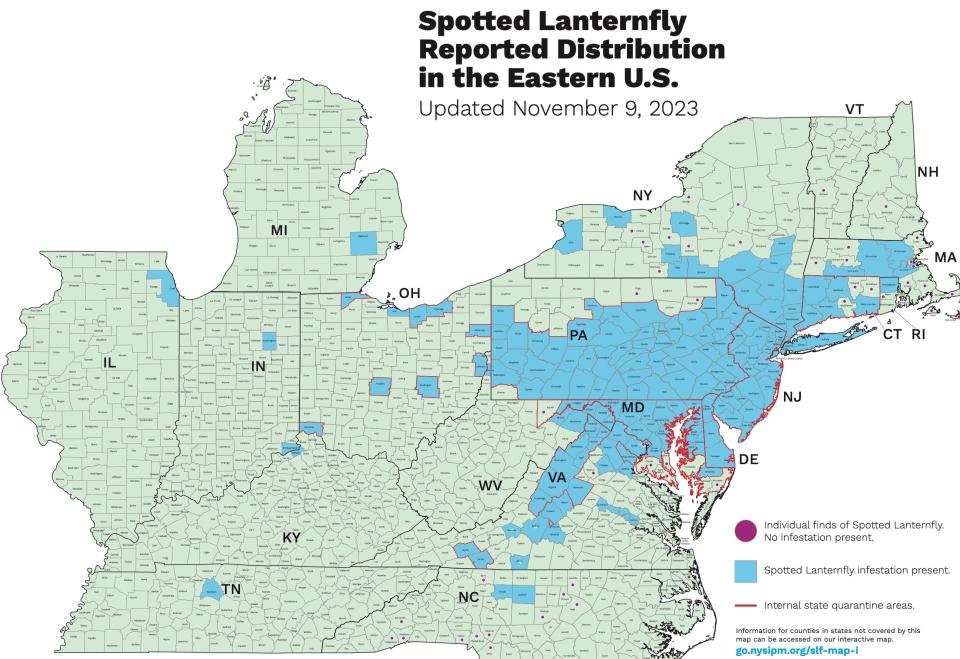

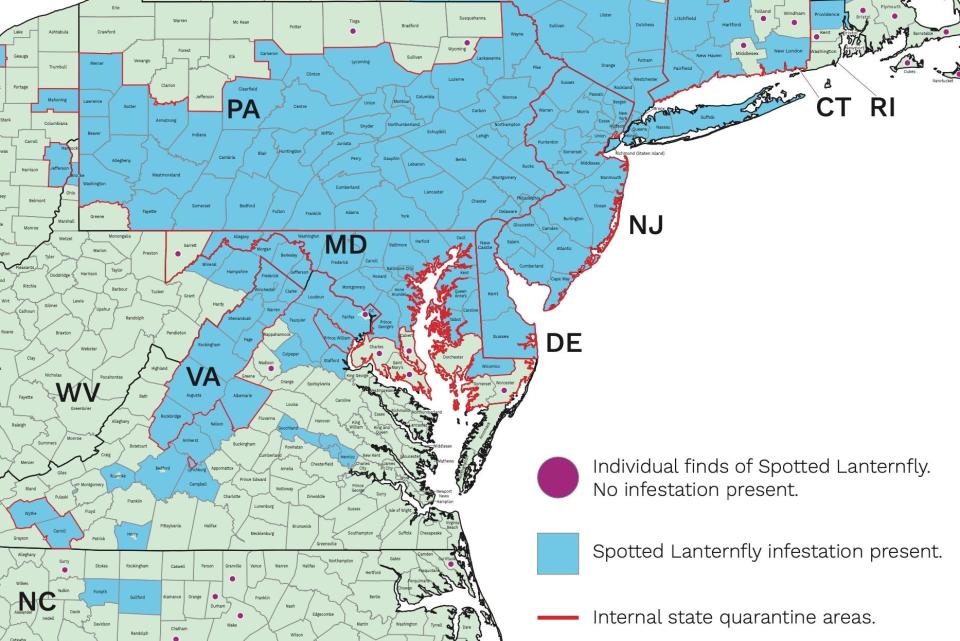

While those efforts slowed the spread, spotted lanternfly infestations have reached most counties in Maryland and Pennsylvania, all of New Jersey, and as far west as a county in Iowa, according to a New York State Integrated Pest Management map updated last fall. West Virginia's Eastern Panhandle, Northern Virginia and Delaware are among other areas with infestations.

Leskey said she first encountered the spotted lanternfly when an entomology colleague at Penn State asked her to come look at a new invasive species spreading in eastern Pennsylvania. They went to a vineyard and saw egg masses at the end of vineyard rows.

It reminded her of the 2010 outbreak of the brown marmorated stink bug, another pest Leskey has talked about at the conversation and training center. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Historian Mark Madison, a representative for the lecture series, said the stink bug talk drew about 350 people, the lecture series' largest crowd in its 27 years.

After that visit to Pennsylvania, Leskey committed to working on the spotted lanternfly with her team. This included looking at reports from its native area and other places it invaded, even a visit to South Korea.

Water, emergency services debate: City, county officials debate water capacity and emergency services

Researching natural ways to deal with spotted lanternfly

The encouraging news is South Korea saw the spotted lanternfly population crash between 2012 to 2018 after exponential growth.

Leskey said South Korean officials think a natural enemy curbed the spotted lanternfly population. That enemy is an egg parasitoid, Anastatus orientalis. It is a non-stinging wasp that lays its eggs in the eggs of the spotted lanternfly.

Research is being done in the U.S. on Anastatus orientalis and the spotted lanternfly — under quarantine conditions, Leskey said.

Speaking about spotted lanternfly predators that aren't native to the U.S, Leskey said researchers can't just release those nonnative predators into the environment. A lot of research has to be done and there is a regulatory process to go through as officials have to be careful about the potential impact on local species.

Other "biological control agents" — or natural predators, parasites and pathogens — of the spotted lanternfly include:

A microscopic roundworm that infects juvenile spotted lanternflies, releasing a symbiotic bacteria that causes septicemia and results in death in 48 hours. Leskey said, so far, the roundworm is not as effective against SLF eggs or adults. In early nymphs, there has been up to 44% reduction.

Orb- and funnel-weaver spiders, though Leskey said they haven't affected spotted lanternfly to the point researchers are seeing a complete reduction.

A non-stinging parasitic wasp called Dryinus sinicus lays its eggs under the wingpad of developing spotted lanternfly nymphs. Leskey said that can lead to a "gruesome death" for the lanternfly when the pupa burst out of its side.

In 2018, a natural infection of the native fungi Beauveria bassiana was effective against SLF nymphs and adults, but not against the eggs. The fungi that rainy summer turned spotted lanternflies into "little pom pom puff balls" and killed them, she said. That fungi works better when applied when its kind of rainy and wet, she said.

North Hagerstown's Luke Frazee: He didn't wrestle for two seasons. But the time away motivates this senior more than ever

What about that sticky honeydew left behind?

When spotted lanternflies feed intensely, sucking on plant sap, they leave behind a honeydew that is sticky and sugary. That honeydew leaves a sooty mold on plants and can reduce photosynthesis and be a problem for fruit trees, Leskey said.

What residents, including some who asked questions after Wednesday's talk, have also noticed is the honeydew attracts other insects like yellow jackets, wasps and ants.

When an audience member commented on the aggressiveness of yellow jackets, Leskey said that occurs more heading into winter as yellow jacket workers start to starve and are competing for resources.

Some beekeepers are bottling SLF honey, from bees that feed on spotted lanternfly honeydew.

After the lecture, a local beekeeper gifted Leskey with a bottle of such honey.

General Assembly opens: Maryland General Assembly session starts this week. Here’s five things to know.

What can you do to curb spotted lanternfly population?

The basic answer to this question is kill them. Squash them when you see them.

They are strong jumpers and the adults can fly. so getting them on the first attempt doesn't always work. Researchers tracked those jumping distances, discovering a nymph can jump more than 20 inches while an adult can leap as far as 8 feet, Leskey said.

Attendees at the lecture shared some of their own experiences, including spraying the bugs with neem oil or a mix of vinegar and water. Another person asked about using Windex.

Leskey said she didn't know about Windex, but said soapy water can probably kill spotted lanternflies, as they are not hard to kill.

Studies about several tree varieties spotted lanternflies feed on showed tree of heaven best supports their "survivorship," Leskey said.

One way the U.S. Department of Ag's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, or APHIS, reduced SLF spread is by hatcheting tree of heaven and squirting a herbicide into that cut, Leskey said. A couple tree of heavens are left behind, treated with a systemic insecticide to kill spotted lanternfly that feed on the remaining trees.

The Delaware Department of Agriculture has more info online on managing SLF with "trap trees" like this.

The Penn State Extension has information online about building circle traps on trees to capture spotted lanternflies, nabbing the pests without using insecticide to trap them.

This is the time of year to destroy egg masses, which each can contain 30 to 50 eggs. The masses look like silly putty smears, which cover rows of eggs. A female can lay five egg masses, Leskey said.

Mating behavior begins in early to mid-September, peaks in October, and continues until major frost kills the adults, Leskey said. Those eggs will start to hatch as early as late April, with many hatching in May and early June.

Check surfaces around your home and property for egg masses. Spotted lanternflies will lay eggs on just about anything, including bark, concrete blocks, a rusty barrel and lampposts, Leskey shared.

An APHIS video recommends scrapping the egg masses into a bag containing rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer and sealing the bag.

Another video by the Penn State Extension says to press down on the egg masses when scraping to kill the nymphs. Otherwise viable ones could survive. That's one reason to drop the scrapings into a bag with alcohol or hand sanitizer and press against the bag so the alcohol touches the eggs.

Leskey said there are even apps people can download to play a game with other people, seeing who can squash the most spotted lanternflies.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail: Spotted lanternflies can cling to vehicles going 65 mph