Homicide in Rochester dropped last year. Can efforts get us to pre-pandemic levels?

Violence in Rochester hit a sharp decline last year. Killings fell 32%, while non-fatal shootings dropped 31% from 2022. The latest data brought some relief to violence prevention workers and city leaders.

But what does it mean?

Assessing the reasons a city sees a drop in violence is tricky. And if you feel the presence of violence in your life, what does it mean for a year's total of Rochester shootings to change?

LaVonn Wilson had just pulled up to a Dollar General with a student from his barbershop apprenticeship program in the passenger seat when he was confronted by the reality of his new role as a mentor and an agent for peace in Rochester.

The local barber was one of 20 community organizations that received city grants last year for innovative programming designed to steer people away from violence. On some days, Wilson’s young trainees showed up to his class ready to cut hair. On others, he wove in lessons on conflict management and financial wellness that challenged the thinking they might find on the street.

The barber was giving one of his students a ride home a few months ago when they stopped at a store just a block away from the teen’s house. Wilson told the boy to stay in the car, but the student refused.

The boy said he had trouble with some people in the neighborhood and couldn’t be caught alone.

“We had a big discussion of why he had that conflict, how uncomfortable it had to be living the next street over from people you have problems with, when you don’t know how far it could escalate,” Wilson said.

The teenager seemed resigned. His attitude toward a potential altercation was sort of, “If it happens, it happens.”

Wilson tried to lay it out plainly: If you resort to violence, you won’t feel better about yourself, he said. You won’t stop looking over your shoulder for what’s next. And you might not see daylight again ― either because you’re buried six feet under or locked away in a jail cell after choices you made.

More: 'Biggest challenge': Homicides dropped in 2023. Rochester led the way in national decrease

How do you really measure success in reducing city violence?

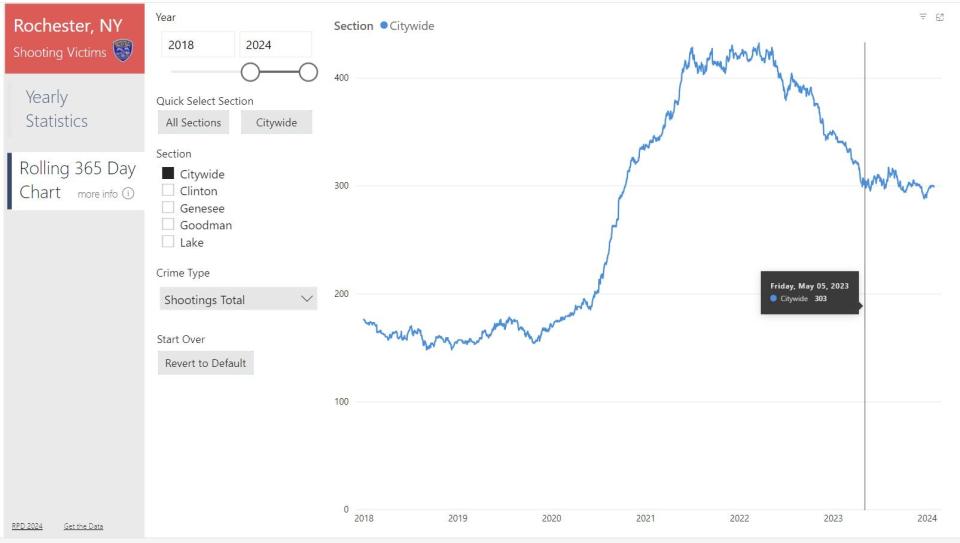

Rochester is coming down from a terrible high. Bloodshed hit an all-time peak in 2021, with 81 homicides. Last year, we had 58 deaths.

Still, Rochester has yet to return to its pre-pandemic numbers, when yearly homicides floated around the 30s. Rochester police said a steady decrease in non-fatal shootings started to plateau last summer, leaving further progress uncertain.

And moments like the one Wilson described are a reminder of the dark reality many residents still face. The fight to curb gun violence is far from over. But what has worked so far ― and how do we expand on that success? It is not clear.

Everyone has their own theory. Rochester has a sprawling grocery list of prevention efforts that include both community and police initiatives.

While most of those efforts follow evidence-based models, their local impact has never been studied in depth, according to Dr. Irshad Altheimer, who leads RIT’s Center for Public Safety Initiatives.

To truly get a grasp on its gun violence problem, Altheimer said, the city must first invest in a rigorous evaluation of its programming to understand what’s working ― and what’s not.

Homicide rate falls in Rochester, nationwide in 2023

The dip in homicides in Rochester mirrored a national decrease last year, suggesting part of the decline took place naturally, Altheimer said.

Violence nationwide spiked after the Covid-19 pandemic and social unrest following several police killings during the summer of 2020. Both events exacerbated already difficult social conditions, leading to a rise in crime nearly everywhere.

As we move further away from that time, Altheimer said we should see crime rates start to stabilize again.

Early data show homicides across the U.S. fell about 10% last year. If those numbers hold, some researchers believe 2023 will have seen one of the largest single-year reductions in homicides in decades.

And in Rochester, Altheimer said it was also normal before the pandemic for shootings and homicides to jump or fall between 15% to 20% year over year.

Those typical changes must be accounted for when looking at this year’s data, he said.

That doesn’t mean local efforts are futile.

Altheimer said Rochester has an abundance of people and organizations trying to halt violence at the ground level. Their work is painstakingly involved. They canvass city streets to offer resources and send response teams to homicide scenes and hospital beds.

Rise Up Rochester: Go inside the race against the clock to help victims of violence in Rochester

Rochester police are short-staffed, still down about 100 officers during one of the worst spates of violence in the city’s history. Still, the police department created a new task force last year to investigate non-fatal shootings with the same resources they’d apply to a homicide case.

Until the city studies these efforts, though, Altheimer said it’s impossible to know for sure what and how much of an impact each program is having.

“If you want to definitively say it’s local factors, you have to have an evaluation that’s able to parcel out all of those (broader social trends),” he said. “We haven’t been able to disentangle that. … I think if we want to have answers, we have got to get serious about measurement.”

Violence in Rochester is falling. What’s behind the change?

Outreach workers found themselves walking Chili Avenue on a sunny day in May, attempting to replace a feeling of defeat in the neighborhood with solidarity and hope a day after two people were shot there.

Several organizations were present, handing out pamphlets and speaking with residents mowing their lawns. They understand that collective action is needed if they want to meet all the pressing needs of victims and perpetrators of violence in Rochester.

Rise Up Rochester coordinates emergency housing and buys groceries for people touched by violence while they are trying to get back on their feet. Pathways to Peace finds mentors for troubled youth. Advance Peace uses credible messengers to mediate conflicts before they turn violent.

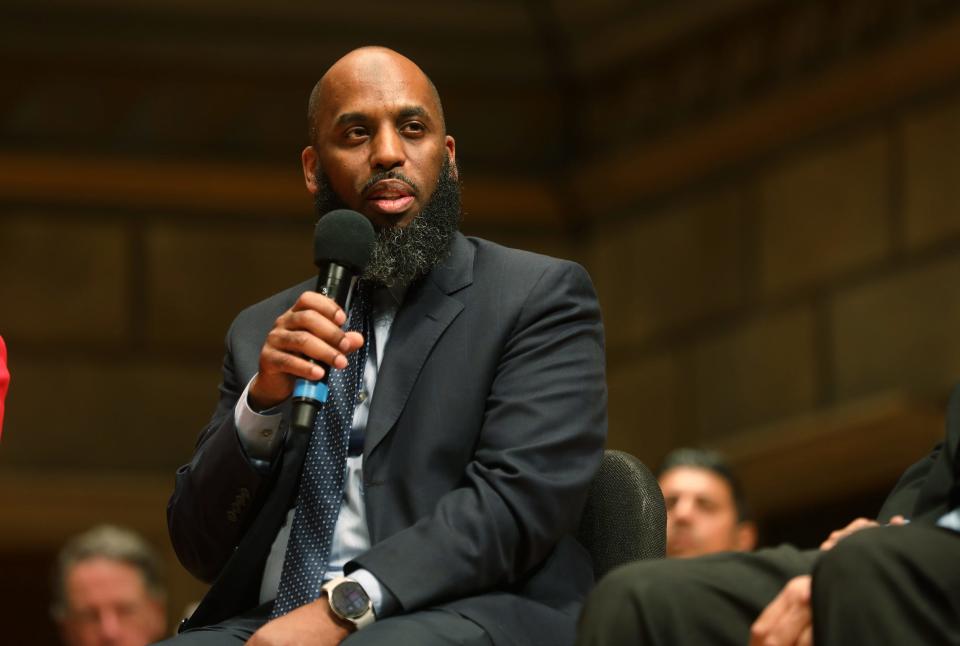

Anthony Hall, a well-known violence prevention worker in Rochester, believes the change we’ve been seeing is a result of these agencies shifting to a cognitive approach to combat violence, addressing mental and emotional wellness in the people they serve alongside physical needs.

“It’s restorative practice, coupled with empathy, compassion, love,” said Hall, who now leads the Community Resource Collaborative. “To shift someone’s mindset it’s not just a job or housing, it’s how they view themselves externally and internally.”

The Rochester Police Department is also leaning on partnerships to drive change.

Last year the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives set up a 24/7 hotline for RPD, where an officer can reach an on-call agent to evaluate if and how to apply federal charges to repeat violent offenders.

RPD also purchased a machine that can scan bullet casings in house. Previously, an officer had to send the casings to a lab for images, and then send those to an ATF office in Atlanta for analysis. That process could take up to nine months to see results.

The machine, coupled with the ATF partnership, means RPD can now match casings from a crime scene to a potential weapon within days.

Capt. Greg Bello said the changes will also enhance prevention efforts by helping officers identify in real-time which groups of people are fighting and where.

“While we might not have enough to charge a person for shooting into a house or shooting into the air, what we can do is start attacking that with our focused deterrence, with our dispute mediation, with our (partnerships with) Pathways to Peace or Rise Up Rochester, whatever it may be,” he said.

Wilson, from the barbershop program, is less sure about his impact on the city’s gun violence.

He doesn’t have any true way to measure whether his work is effective. He just knows that for six weeks at a time, half a dozen teenagers are showing up to his barbershop ready to work and open to the thoughtful discussions he puts before them.

Some of his students may not have been on a destructive path in the first place. But Wilson figures if he reaches just one person who was, it will have been enough.

It could mean one less shooter. It could mean one less death.

Antagonized: How can we defuse conflict on the streets of Rochester if we're caught in it?

More: Can barbershop talks curb gun violence in Rochester? LaVonn Wilson thinks so.

— Kayla Canne reports on community justice and safety efforts for the Democrat and Chronicle. Get in touch at kcanne@gannett.com or on Twitter @kaylacanne.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Rochester NY gun violence: What's behind drop in shootings, homicides?