WNC camper death: NC Health records show prior child death violations; delayed search

A therapeutic outdoor camp temporarily shut down and under criminal investigation for the Feb. 3 death of a newly arrived camper faced a similar situation a decade ago — that was when it was hit with a severe penalty and criticism in the tragic aftermath of a camper's 2014 death that documents recently obtained by the Citizen Times show might have been avoided but for multiple camp missteps.

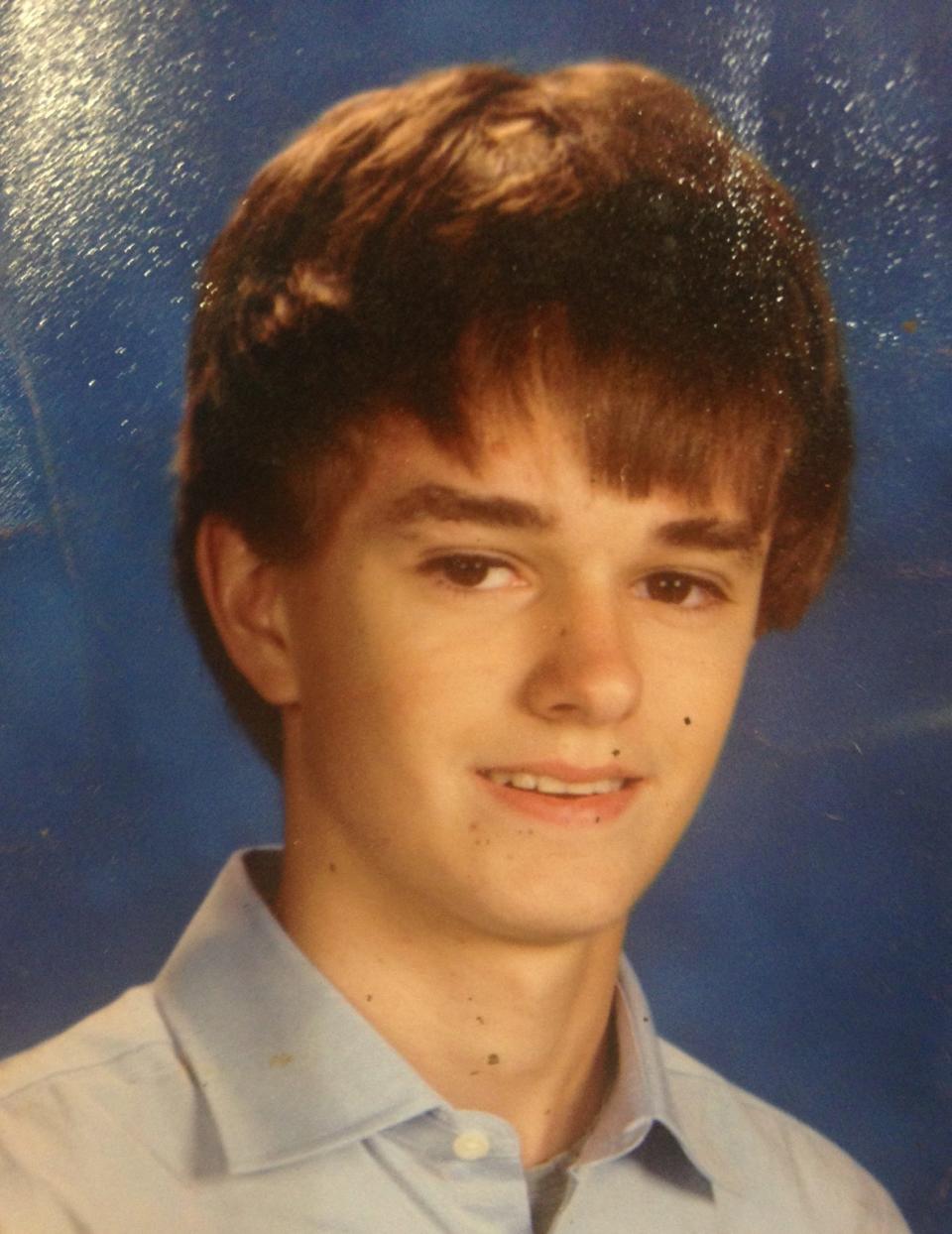

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services documents obtained by the Citizen Times through a public records request show how Lake Toxaway-based Trails Carolina faced sanctions from state health regulators and criticism from law enforcement after the death of Alec Sanford Lansing, 17, of Atlanta on Nov. 22, 2014.

Lansing had gone missing from a campsite in Jackson County where he had been staying with three Trails Carolina staff members and six other campers. His body was found 12 days later, less than a half-mile from the campsite, the documents say. The medical examiner said he had a broken hip and died of hypothermia. Health regulators found that staff failed to keep watch on Lansing despite categorizing him as a higher risk and did not have a plan for calling law enforcement when a child went missing. One law enforcement officer, whose name and agency were redacted in the documents, said Lansing might have been found alive if camp staff had notified law enforcement immediately.

NCDHHS staff declined to comment March 20 on the ongoing regulatory investigation into last month's death of a 12-year-old at the camp. A spokesperson for Chuck Owenby, sheriff of Transylvania County, where the camp is based, said the criminal probe was still on hold as deputies awaited an FBI forensic analysis of camp computers and a toxicology report from the state medical examiner.

Along with the current criminal and regulatory investigations, Trails Carolina was recently sued by two former campers who said the camp should have taken steps to prevent them from being sexually assaulted by other campers. One case has been settled. In recent years, the camp has had other notices of deficiencies, including five from 2018 to 2023.

The National Youth Rights Association, a critic of the "troubled teen industry" said what happened to Lansing was a sad forecast of last month's death.

"If you were to look at previous coverage of this very facility there have been red flags everywhere," the NYRA said in statement. The Citizen Times reached out to the group for further comment.

Trails Carolina Executive Director Graham Shannonhouse who lives in the Ramble subdivision near Asheville did not respond to phone calls and emails. Camp spokesperson Wendy D'Alessandro responded in a statement saying Trails Carolina continues to "pray for healing and peace for everyone involved" in Lansing's 2014 death.

"Everyone in this profession, including the State of North Carolina, shares a common purpose: helping children and their families heal. We value and support regulation and oversight for this industry so the profession can continue learning and improving. Trails has been cited, and from those citations, the program has made immediate changes to policies, protocols and training," she said.

'Harm, abuse, neglect'

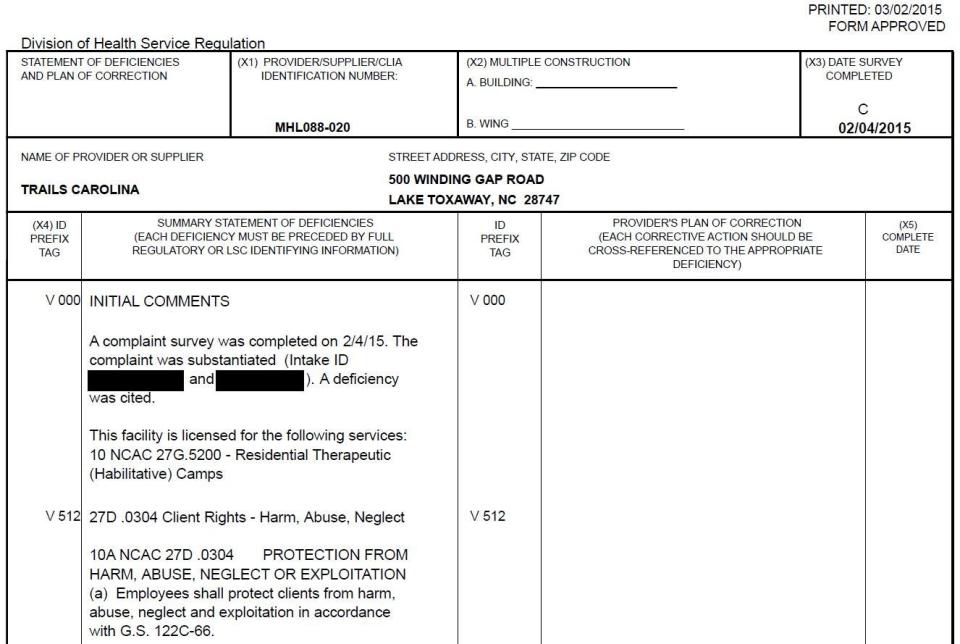

In a March 3, 2015, certified letter, N.C. Mental Health Licensure Chief Stephanie Gilliam told Shannonhouse the high-end camp had violated Lansing's right to "protection from harm, abuse, neglect or exploitation," as provided by state law. Gilliam assigned a $12,000 fine.

The camp has an average price of $66,000 for an 83-day outdoor experiential mental health treatment program, according to its website.

NCDHHS also sent a notice of deficiency summarizing multiple corrections that must be made. The camp faced no shutdown at that time, unlike last month's decision to close the camp until at least April after the death of the 12-year-old child. That was after health regulators said camp staff stopped them from accessing other children for three days. The camp, through its spokesperson, denied it had done anything wrong.

Asked why regulators had not closed the camp after Lansing's death, DHHS spokesperson Kelly Haight replied March 22, citing state law pertaining to the department's powers. The law says a mental health facility's license can be suspended when "public health, safety or welfare considerations require emergency action." A license can be revoked when a facility's failure to follow state rules endangers "the health, safety, or welfare of individuals in the facility," she said.

Trails Carolina had a right to appeal the 2015 penalty in response to Lansing's death but did not. After his death, Jackson County sheriff's deputies opened a probe into the camp's actions, Capt. Tony Cope told the Citizen Times last month.

"There was a criminal investigation completed, but it was determined that it was more of search and recovery effort. It was determined it was an accidental death, therefore no charges were brought," Cope said of the 2014 incident.

But according to the nine-year-old deficiency notice, dated Feb. 4, 2015, a law enforcement officer and an official involved with the search spoke about frustrations that the search wasn't started until nearly two days after Lansing went missing.

Notes in the statement of deficiency said, "Interview on 12/8/14 with an officer of a local (redacted) revealed:

If the camp had contacted their office immediately law enforcement would have come to the scene or made contact with someone in charge and then notified the volunteer rescue squad to begin a 'hasty search.'

'Hasty search' means quick, fast and in a hurry. This type of search would have placed people on roads and the marked trails.

The volunteer rescue squad could have been there within an hour had they been notified. The officer stated he believed if more people had been in the woods searching for (redacted) they may have been able to hear (redacted)."

Marks on a tree near Lansing's body, led investigators to believe that he fell from a tree and broke his hip, landing in a stream. Jackson County sheriff's spokesperson Maj. Shannon Queen, at the time, described the terrain as "rugged and treacherous." Some of the coldest weather of the season had settled over the mountains, with temperatures dipping into the mid-teens Nov. 19, the Citizen Times reported at the time.

'Computer prodigy' and devoted brother

Lansing was born in Atlanta but spent a large portion of his life in Tennessee with his mother, Pamela Lansing, according to his online obituary. He and his mother relocated to Atlanta in 2012 to be closer to his father, Stephen Lansing. Pamela Lansing declined to comment to the Citizen Times. Stephen Lansing did not respond to messages.

A high school senior at Ben Franklin Academy, Alec Lansing was described in his obituary as a computer prodigy and athlete who taught himself Swedish.

"Alec had a keen wit and verbal prowess that enabled him to espouse a worldview showing wisdom well beyond his tender years. He cared deeply about the injustices in the world, eloquently defending those who were wronged or mistreated," it said.

Lansing loved animals and his family and was devoted to his older brother, Brenan, who died in 2012, the obituary said.

"The loss of his brother was a devastation and heartache from which Alec never fully recovered," it said.

Delayed search and rescue effort

At camp, it was noted that Lansing did not have a "history of elopement."

On a Saturday before then, likely Nov. 8, his mother called and said she wanted to pick him up, according to "Therapist #1" interviewed Dec. 3 by health regulators. Lansing's mother said he "had completed enough of the program and needed to return to school." His mother was informed they could arrange a call on "Tuesday" − which was likely Nov. 11 − to discuss his "transition out of the program."

Some time in his stay, the date of which was redacted, Lansing was elevated to a "Level 2" status, meaning for his safety, staff were to have visual contact with him at all times. But on the Nov. 10 camping trip he asked to go to the "loo" and a staff member allowed him to go by himself, using a system of calling out his name and waiting for him to call back. At one point Lansing stopped responding, the records say. The time that happened appears to have been redacted, though law enforcement records showed officers were notified at 6:30 p.m., which one officer said was approximately four hours after Lansing went missing.

Once notified, deputies interviewed a clerk at a gas station in the Cashiers community who said she had seen someone who looked like Lansing. He was described as 5 feet, 11 inches tall, weighing 140 pounds with brown hair and brown eyes and last seen wearing a red, long-sleeve fleece with black pants and gray boots and carrying a backpack. Looking at a photo presented by deputies, the clerk said the person she saw walk by at 6 p.m. was Lansing. That turned out to be untrue, and it further delayed the call for an official search, the records show.

After determining the person seen was not Lansing, officials planned a search and rescue with a helicopter, though that effort turned up nothing, law enforcement records said. A ground search with "all-terrain vehicles, hikers and the (N.C. Highway Patrol) helicopter was initiated." The U.S. Forest Service, highway patrol, sheriff's office, Glenville-Cashiers Rescue Squad, Jackson County Emergency Management and Cashiers Fire Department participated.

Lansing's orange safety vest was found below the latrine area. On Nov. 14, four days after he went missing, the helicopter was redeployed, according to Citizen Times reporting. A K-9 team also joined. Searchers found a fanny pack with books in it was Lansing's. But on Nov. 16, with no other leads, the search was scaled back. More than 100 people had participated.

Lansing's mother, frustrated with the search had hired a private investigator, according to a law enforcement interview with her.

At 10:30 a.m. on Nov. 22, all search teams were notified to terminate their efforts. Lansing's body had been located in a "remote area" in a creek at the bottom of a gorge with clothing that matched his description.

"Search teams had covered the area before, but the vegetation was so thick down around the creek that the body could easily have been missed unless you were right down in the creek bed," said health regulators' account of the police report.

In a Dec. 4, 2014, interview, Shannonhouse, the camp executive director, acknowledged that staff should have maintained visual contact with Lansing and that a latrine should have been established with a tarp closer to camp.

"The camp had no specific protocol for contacting law enforcement," the deficiency notice said, quoting a redacted camp official who said "After police are called 'you lose control.'"

Camp staff were assigned to correct those and other measures.

In a Dec. 22, 2014, interview of the official involved with the search, the official found fault with the time it took to start the search. They said the the camp felt the claimed sighting near the gas station "was a good match to (Lansing) and felt confident that (he) hadmade it out of the woods.

The official said it was "troubling" that the camp staff "could make the assumption that 'a city kid' could make it out of the wood(s) that easily."

The camp sought to rebut that in its March 22 statement to the Citizen Times, saying it was law enforcement that reported the possible sighting and that led the search and rescue efforts.

"The program had no decision-making power to delay or direct the search," spokesperson D'Alessandro said.

The official said the search and rescue was not called until after dark Nov. 10, and because Nov. 11 was spent exploring the false sighting, "the real search did not start until (Nov. 12).""(Lansing) was found 530 yards from the campsite. A (redacted) representative had informed (redacted) that (Lansing) died the same day (he) left.

"The first 12 to 24 hours was critical," the official said.

Meanwhile, the camp remains closed as family of the 12-year-old camper and officials wait on the important next steps in the death investigation, including the medical examiner's findings.

More: Word from the Smokies: Training essential to park’s search and rescue

Great Smoky Mountains search for missing man intensifies near Deep Creek

Joel Burgess has lived in WNC for more than 20 years, covering politics, government and other news. He's written award-winning stories on topics ranging from gerrymandering to police use of force. Got a tip? Contact Burgess at jburgess@citizentimes.com, 828-713-1095 or on Twitter @AVLreporter. Please help support this type of journalism with a subscription to the Citizen Times.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Western NC camp child death: violations, search delayed in prior death