Biden hopes to escape the shadow of Obama's immigration policies

It happened quickly.

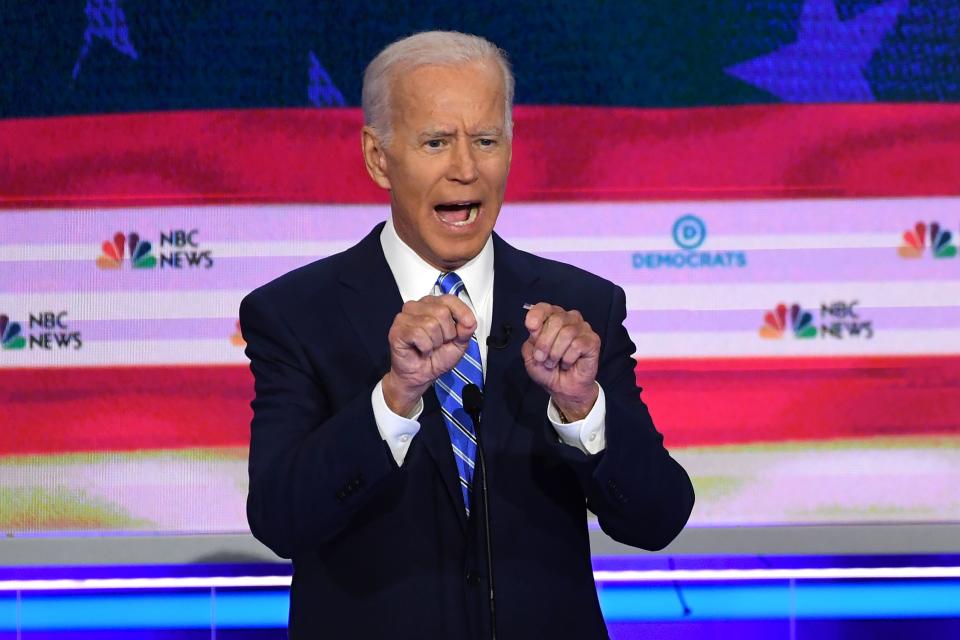

Jorge Ramos, the influential Univision anchor and one of the moderators of the ABC News Democratic debate in Houston in September, turned from the mass shooting in El Paso, Texas, that targeted Latinos, to immigration, and pressed Joe Biden over his vote as a senator for 700 miles of border fencing, and the 3 million deportations during the Obama administration, when Biden served as vice president.

“Why should Latinos trust you?” Ramos said, accusingly.

Biden was ready. As he has previously, Biden said, “Comparing [Obama] to the president we have is outrageous, No. 1. We didn't lock people up in cages. We didn't separate families. We didn't do all of those things.”

“Did you make a mistake with the deportations?” Ramos tried, again.

“The president did the best thing that was able to be done at the time,” Biden offered.

When the debate concluded, Biden approached Ramos and had a conversation that a high-level Univision source with knowledge of the exchange described as contentious. Biden’s message was that Ramos’s questions were a low blow, that he fought for “Dreamers” as vice president, and that while they didn’t get deportations right early on in the administration, they did by the end. The Biden campaign did not dispute that Ramos and Biden discussed the subject after the debate.

As Biden readies for another Democratic debate Tuesday night, his record on immigration has to be on a long list of concerns, along with President Trump’s attacks on him and his son Hunter, his vanishing lead over Elizabeth Warren in recent polls and the danger of another ambush like the one Kamala Harris launched over his record on school busing. The exchange with Ramos echoed the previous debate, when activists interrupted Biden, chanting, “Three million deportations! Three million deportations!” In an interview afterward, as they drank beers, the activists from Movement Cosecha were asked what they actually want to hear from Biden.

“Biden hasn’t apologized. He wants the Latino vote, but he’s not saying, ‘I’m sorry,’” Ofelia, an activist with the group who withheld her last name because of the current immigration climate, told Yahoo News in Spanish. “When you were VP you didn’t speak against it, but now you have a chance to change that. We didn’t forget. Say, ‘I’m sorry, we’re not going to do that anymore.’”

“There can be no daylight between Biden and Obama; he’s always going to get Obama’s back,” a source close to the campaign explained. “He knows mistakes were made at the beginning [on deportations], but they did get it right at the end.”

Biden doesn’t grasp — or perhaps genuinely isn’t concerned — that by defending Obama and refusing to reckon with his immigration policy and record of deportations, he’s sending a message to Democrats and activists that a Biden administration will be no different.

But that won’t be the last time Biden will be put on the defensive over the issue, as he runs for the presidential nomination in a party where even as Obama remains personally popular his immigration policies are increasingly viewed as problematic. More than the crime bill, or busing, two issues from his past that have been heavily litigated during the campaign, what Biden believes on immigration and the moral authority he brings to a potential fight with Trump could help decide whether he is the one who takes back the White House for the Democrats to begin the job of undoing Trump’s policies.

Digging into Biden’s record reveals tough votes during his long Senate career that activists will want him to answer for, but also a story he can tell about his decades-long support for admitting immigrants to the United States and a bipartisan approach to the issue that bolster his argument that he has the experience to actually govern.

Biden has long described immigration as stitched into the American fabric, as he did three decades ago, during the final Senate session for the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, better known as Ronald Reagan’s amnesty law.

Biden, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time, expressed hope that legalizing undocumented immigrants would “move a growing underclass living in the shadows into the daylight of citizenship and opportunity. These individuals must become full participants in our society, not just the object of our concern.” He added: “Immigration has always been in the national interest, and the amnesty program in this bill represents the best of that tradition. By turning strangers in our midst into friends and neighbors we trust."

In 1994, tucked inside the controversial crime bill Biden designed was a Battered Women Immigrant Provision. This section “allowed undocumented women physically abused by their partners to petition for legal status themselves. Previously, they were only able to do so through a husband who had legal status, putting untold numbers of women at the mercy of their abusers,” wrote socialist magazine Jacobin in a discussion of Biden’s record earlier this year. But the thrust of the article was contained in the headline: “Joe Biden, Anti-Immigrant Enabler.”

One of the elements in that assessment was his vote for the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996. The bill, widely supported by Democrats at the time, is now viewed as a vehicle for making deportations easier, establishing the practice of deputizing local law enforcement to enforce federal immigration law, and creating the punitive three- and 10-year bars, which prohibit reentry based on time spent in the country illegally. In 2016, Rep. Raúl Grijalva of Arizona and 32 other Democrats put forward a resolution calling for repealing much of the law.

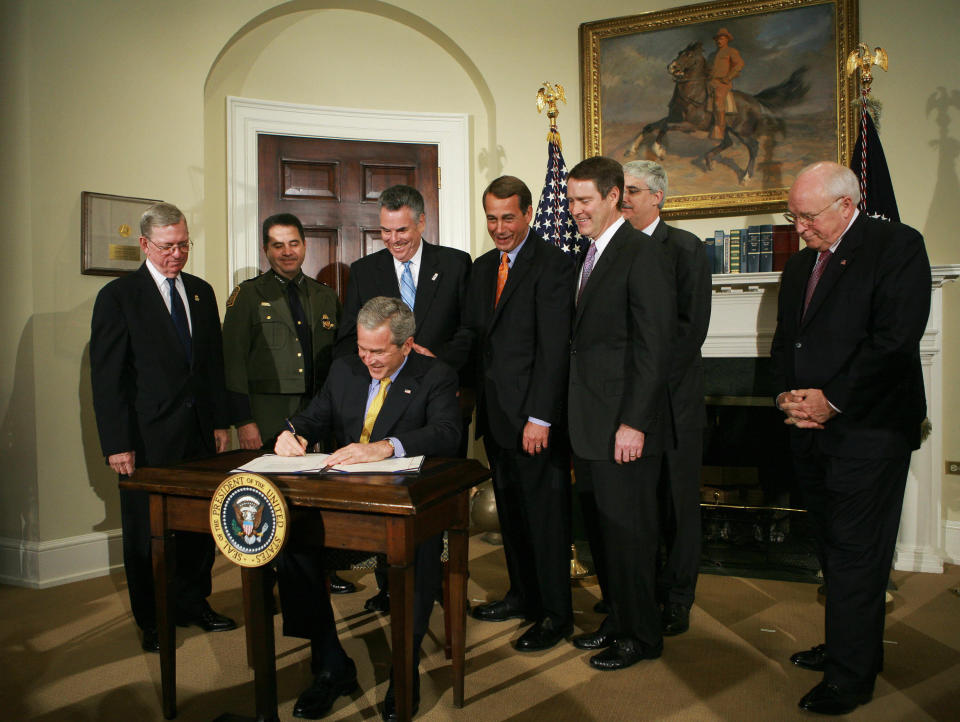

In 2006, Biden, along with other Democratic senators including Obama and Hillary Clinton, voted for the Secure Fence Act, which authorized 700 miles of fencing along the border. This was part of a pattern by Democrats, including Obama, to offer border security enhancements in hopes of winning concessions on legalizing undocumented immigrants. Progressives now regard that as a failed strategy.

“The 2006 vote f***ed us all,” said a veteran Democrat on the Hill who didn’t want to be quoted by name. “That’s where the majority of the Democratic Party was — being told you need to get the border secured if you want to get to the next step.”

Biden then ran for president in 2008 on an immigration plan that was closer to, say, Jeb Bush’s 2016 platform, than what Biden supports now, according to an archive of his campaign website. While seeking to provide a path to bring 12 million undocumented immigrants, including 1.6 million children, out of the “shadows,” Biden also proposed increased appropriations for border patrol agents, opposed driver's licenses for undocumented immigrants, and said, in a debate, that sanctuary cities shouldn't be allowed to ignore federal law.

Asked to comment, current campaign officials told Yahoo News the immigration policies of Biden’s administration would be informed by the policy he implemented as vice president, specifically his work in Central America, as well as his recent public statements.

How Biden viewed immigration during his time as vice president was often revealed by a story he loved to tell then.

Biden told the story to many people at the time, but it’s saved for posterity on an “Ask the White House” YouTube video from December 2013 featuring Cecilia Muñoz, Obama’s domestic policy counsel. In Biden’s telling, as the administration pushed for passage of the Senate’s bipartisan immigration reform bill, Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding father, said China was looking for America’s “black box,” the thing that enables it to constantly remake itself. “I can tell them what’s in that black box — immigration,” Biden said. “A constant stream of immigration from our inception. That’s what makes us the most innovative, the most unique country in the world. At its core we’re a nation of immigrants.”

But that view was challenged, during the summer of 2014, as a wave of unaccompanied minors came across the border — some 60,000, with internal estimates that it could have reached as many as 100,000, according to former White House officials. With Biden in the midst of a multicountry swing through Latin America, advisers recall the West Wing calling with an urgent directive: He had to sit down with the heads of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, known as the Northern Triangle countries, and deliver a stern warning that they should do as much as possible to stop migrants from coming to the U.S.

The vice president’s thinking at the time, according to Juan Gonzalez, a Biden adviser on Latin America, was “we can’t just ask these guys to not send people up to us; obviously they’re leaving for a reason. We should offer a carrot here to address why people are leaving.” Biden’s message to the Northern Triangle leaders became, “If you guys can develop a serious plan together, I promise that we will back you.”

Backing them came in the form of a $750 million bipartisan aid agreement for which Biden took the lead in convincing members of Congress that it was worth it. The sales job involved him pitching Republican members that it made no sense to devote 90 percent of federal funding to dealing with the crisis on the border, but only 10 percent on helping governments address and stem the root causes of migration.

In a 2018 Washington Post op-ed titled “The Border Won’t Be Secure Until Central America Is” — timed to Trump’s signing an executive order whose purpose was to end family separation — Biden wrote that as vice president he supported Congress in ”tying the aid package to concrete commitments by regional governments to clean up their police, increase tax collection, fight corruption and create the opportunities necessary to convince would-be migrants to remain in their countries.”

The episode could foreshadow how Biden would govern, leveraging his relationships in Congress and in Latin America, distinguished from Trump, who declared a national emergency on immigration while seeking to curtail or end asylum programs and aid.

“It’s a counterproductive policy of threat that cuts off your nose to spite your face, and there have already have been indications that Congress thinks the administration is acting outside the law by cutting off programs that have already been appropriated for certain purposes,” said Cynthia Arnson, director of the Latin America Program at the Wilson Center think tank.

“There’s no way Congress would have appropriated the resources if not for his advocacy,” Obama adviser Muñoz told Yahoo News. “He led on addressing the reasons people were migrating in the first place, in a hands-on way.”

Activists who worked with the Obama administration said they didn’t really interact with Biden on DACA, the program that deferred deportation for undocumented immigrants brought across the border as children and raised in America. But they acknowledge that he took the lead on Central American issues during a perilous time for thousands of migrants coming to the country.

During a May 2014 meeting at the White House between Obama and activists, where the president announced he was going to enact a second executive action on immigration known as DAPA (Deferred Action for Parents of Americans), Biden showed up to share how he was engaging with his counterparts in Central America, said attendee Marielena Hincapié, executive director of the National Immigration Law Center. “We’re not going to address the situation of migrants coming from Central America unless we’re looking at the root causes; we have to be looking at migration not as a domestic issue, but from a foreign policy perspective as well,” she said of the current dilemma.

Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign discussed tying immigration to foreign policy at the highest levels, according to the campaign’s former national political director, Amanda Renteria, due to Clinton’s experience as secretary of state, but never rolled out a plan.

“That’s what makes Biden’s immigration work around Latin America more attractive,” Renteria said.

An advantage for Biden over some of his Democratic opponents — who advocate decriminalizing border crossing — is that Trump couldn’t charge him with supporting “open borders.” The former vice president could invoke talking points about “smart” border security, while hammering the president on issues where there is a stark contrast, like family separation and eroding due process for asylum seekers.

If Biden openly explains and defends his record on immigration, he could emphasize the contrast with Trump and make immigration a top legislative campaign priority early in his presidency, pleasing advocates who seek major reforms to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). But party officials, including some who support Biden or are advising the campaign, say he needs to understand that he has to begin by admitting Obama made mistakes.

“Is Biden going to continue being the deporter in chief or is he going to learn from the mistakes and chart a different path on immigration?” asked longtime Nevada Democratic strategist Andres Ramirez, who worked with the Obama administration on projects such as getting Latinos signed up for the Affordable Care Act. “Trump’s record on immigration is an abomination, but Latinos are right to demand clarity on where candidates stand on this issue.”

Biden’s team is being advised on immigration policy by a loose network of unofficial advisers and stakeholders on domestic immigration and Latin American issues, and includes an intentional focus on recruiting and engaging Latina validators, say women who have been reached out to by Biden senior adviser and former Latino Victory president Cristobal Alex.

Still, Cristina Jimenez, the executive director of United We Dream, who met with the campaign this summer to give her organization’s views on how it should approach immigration, said that because of the rise in deportations under an administration Biden was a part of, her organization will be asking not just how Biden would govern differently than Trump, but also differently than Obama.

“I look forward to hearing how they will help our communities, without harming our communities more,” she said.

"Vice President Biden has said previously that early in the Obama-Biden administration immigration laws were not being enforced effectively, which is why in 2014 they changed course,” the Biden campaign told Yahoo News. “The administration reprioritized enforcement that went after violent criminals and repeat offenders, not families.

The campaign said Biden believes fixing the system starts with addressing the root causes of immigration abroad and working toward comprehensive immigration reform at home, including a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and smart border security.

“Those are the big contours, but what’s obviously different — if he’s elected president he knows how to get it done,” a source close to the campaign said, again pointing to Biden’s Latin America work and relationships in Congress. “As much as folks can’t stand the idea of Congress, you need to pass legislation. At the end of the day you can’t rely on executive action.”

Biden wants voters to see him as someone who can reach across the aisle, but he would be seeking to pass immigration reform in a political environment even more polarized in Trump’s wake. That’s why activists want Biden to pledge to use his finite political capital to make immigration a legislative priority immediately as president, beyond using executives orders to rescind Trump policies on day one, as he has promised.

Janet Murguia, president of UnidosUS, the nation’s largest Latino civil rights and advocacy organization, who called Obama the “deporter in chief” in 2014, said she does expect Biden and other Democrats to make immigration a priority in their first 100 days because of the damage done by Trump. “No question, 100 days is still a good measure to evaluate how a candidate will execute once they’re president,” she said.

The other area where Biden can show he’s paying attention to the realities of immigration in America, Democrats argue, is in reining in ICE, CBP and DHS, which are not hallowed institutions created by the Founding Fathers, but were instead all created post-9/11, over four months from 2002 to 2003.

The Obama administration infamously had difficulty getting ICE to enact its directives, like the Morton memo, which called for prosecutorial discretion on veterans, people who have lived lawfully in the U.S. for years, pregnant women, and domestic violence and trafficking victims, in favor of focusing on national security risks, gang members and serious felons. Yet the Trump administration has had no problem getting these same agents to zealously implement its zero tolerance agenda.

“There needs to be a conversation about the brutality used by agents at the border. Seven children died at the hands of this administration,” United We Dream’s Jimenez said.

The former vice president left room for modifying the scope and organization of these agencies when he was in the Senate. While Biden voted to create DHS, in a floor speech before the vote, he said he feared “because of the speed with which we considered this proposal, the rapid, sweeping reorganization it immediately envisions and the prospect for abuse in several of its provisions, I fear this bill will need to be revisited several times and its implementation will need to be closely monitored by Congress if we hope to get it right.”

Biden echoed those ideas during a July meeting with the Congressional Hispanic Caucus (CHC) and again during his meeting with Latino leaders in August, according to meeting attendees, who said his message was that there is a culture of corruption within ICE that needs to be rooted out. As a show of solidarity with CHC members in July regarding the need for better leadership at DHS, Biden surprised some in the room when he turned to Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard, D-Calif., and said, “Well, I think you would be great.”

Biden’s Latino supporters like Nevada state Sen. Yvanna Cancela, who endorsed him on the day he launched his campaign despite overtures from seven other contenders, believe that Biden would be willing to enact these reforms as president.

“If you look at the CPB mission, it’s related to terrorists, so when you have that agency doing the work of dealing with migrant children and families at the border, it essentially means we’re treating them like terrorists,” she said. “I trust that because of his experience the VP will know how to change those agencies from the inside out.”

Now Biden just has to start talking about it.

Adrian Carrasquillo is a national political reporter covering 2020 and Latino issues who has written for NBC News, BuzzFeed, Politico Magazine and Texas Monthly.

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Greta Thunberg: Powerful men 'want to silence' young climate activists

Driven from Central America by gangs and finding refuge in Kentucky: One woman's story

'I talk about power because you're not supposed to': Why Stacey Abrams still wants to be president

Nation's intelligence officers are resigned to serving a president who doesn't trust them

Before Black Lives Matter: Exhibition pays tribute to an earlier NYPD killing of unarmed black man

360: U.S. pulls support for Syrian Kurds: What happens next?

PHOTOS: Turkey presses Syrian assault as thousands flee the fighting