DeSantis cuts $28 million from disease treatment at Florida prisons as pandemic's toll worsens

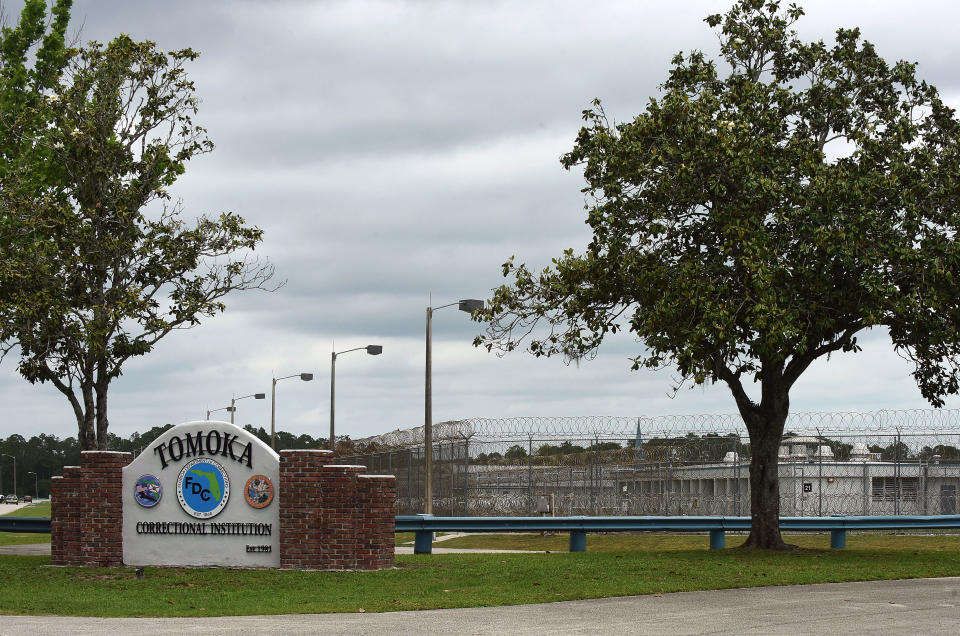

WASHINGTON — The coronavirus is raging inside Florida’s prisons, with about 2,400 inmates and 600 employees testing positive for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. Twenty-three inmates have died. Last week, two prison system contractors became the first people working within one of the state’s 16 prisons to succumb to COVID-19.

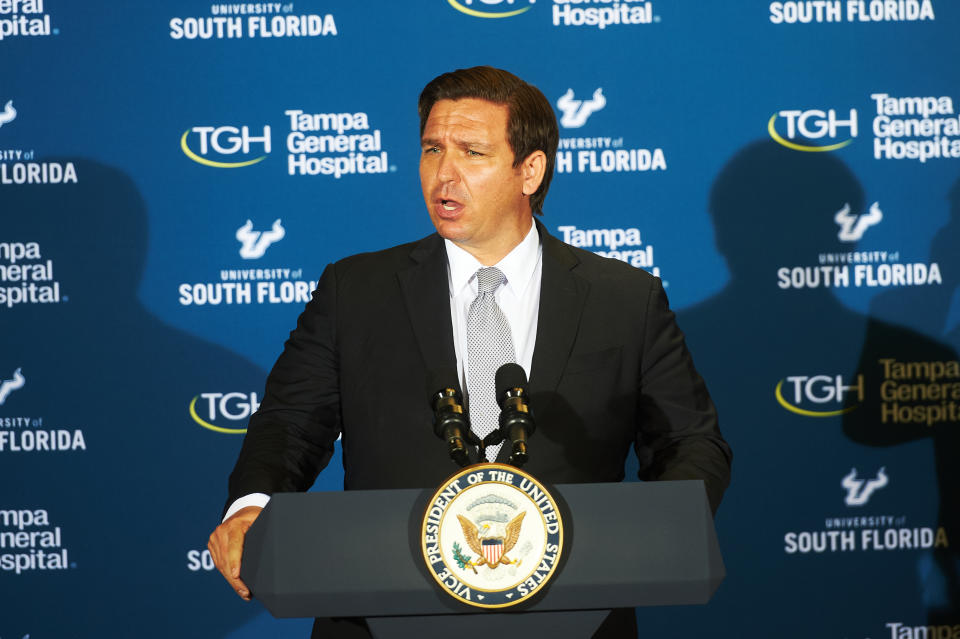

With the third-highest prison population in the United States, after Texas and California, Florida could be putting its 99,000 prisoners at acute risk of contracting the coronavirus, criminal justice advocates worry. Nevertheless, Gov. Ron DeSantis used his veto powers late last month to excise from the state budget a $28 million initiative to treat prisoners for hepatitis C and the coronavirus.

The veto was one of many DeSantis made in the proposed $93.2 billion state budget. Among the dozens of other rejected funding items were a $530,000 security grant for a synagogue in Tallahassee and $500,000 to support babies born with visual impairments, not to mention a host of remote-learning and physical infrastructure programs.

The governor did, at the same time, preserve wage increases for state employees.

DeSantis touted the final budget as “realizing historic savings.” He has argued that cuts were necessary owing to a decline in revenue, as the coronavirus is in the midst of dealing a crippling blow to Florida’s tourism-dependent economy, which has already lost some $900 million in tax revenue. Those losses could run into the billions, analysts say.

The savings may thrill fiscal conservatives, but the cuts have angered increasingly vocal detractors who charge that the first-term governor is more interested in pleasing President Trump than doing right by his own constituents. He has routinely received among the lowest approval ratings of any governor on his response to the pandemic.

“We understand there’s a significant decline in our state revenue,” Carrie Boyd of the Southern Poverty Law Center told Yahoo News. “However, the prison population should not suffer as a result of the administration’s political decisions.”

DeSantis’s press office did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Although he had warned that the pandemic would require him to use his veto powers, the dreaded red pen passed over many Florida-based corporations, which received $543 million in tax breaks from the state.

“Governor DeSantis has a unique ability to find and execute the most hurtful, damaging and counterproductive moves imaginable,” said Pam Keith, a prominent South Florida progressive who is now running for Congress. In a text message to Yahoo News, Keith called the veto “heartless.”

The $28 million initiative stemmed from a case known as Hoffer v. Inch, a 2017 lawsuit in which three incarcerated individuals sued the state for failing to provide treatment for hepatitis C, an infectious liver disease that has proliferated throughout American prisons. (Mark Inch is the Florida Department of Corrections secretary.)

Some 20,000 inmates in Florida — nearly a fifth of the state’s prison population — are believed to have hepatitis C. The continuing legal battle now concerns Florida’s refusal to treat those in the system who are less severely infected with hepatitis C. In a 2019 ruling, a district court judge charged the state with “deliberate indifference” and ordered those inmates to be treated; the DeSantis administration appealed that ruling to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which could rule as early as September.

The state Legislature allotted the $28 million with the anticipation that DeSantis would lose the appeal and would have to treat those inmates with less severe cases of hepatitis C. At the time legislators were crafting the budget throughout the spring, after the coronavirus had made landfall in the United States.

Predicting that the state would eventually have to deal with the pandemic, legislators wrote the budget item in such a way that the Florida Department of Corrections could also request that the money be used to treat the coronavirus instead of hepatitis C. “We passed this budget as the pandemic was beginning to unfold. It was written into the budget that this $28 million could also be used, or instead be used, to treat or stop the spread of COVID in our state prisons,” state Rep. Carlos Guillermo Smith told Yahoo News.

In response to a question from Yahoo News, the state’s Department of Corrections said that “ensuring inmates incarcerated in Florida’s prisons receive an appropriate level of medical and behavioral treatment” was one of the department’s “core constitutional responsibilities.” A request for more detailed information about those responsibilities went unanswered by the prison system’s public affairs office.

“Now’s not the time to cut funding for a chronic and widespread infectious disease like hepatitis C,” said Dante Trevisanti, executive director of the Florida Justice Institute, which brought the original lawsuit. “Treating hep C is treating COVID,” Trevisanti added.

It is not yet clear just how a patient already ill with hepatitis C would respond to a coronavirus infection. In its guidance on liver disease and the coronavirus, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention explains that liver disease could potentially exacerbate the ravages of COVID-19, whose assault on the human body remains somewhat poorly understood.

DeSantis was initially celebrated by some conservatives for his coronavirus response, but the celebration appears to have been premature. As case counts have risen across the state, he has since been widely criticized for moving to reopen Florida too quickly and allegedly suppressing data.

DeSantis has tried to minimize the outbreak of the virus in prisons, describing the situation behind bars as “a discrete issue that is not really indicative of a community outbreak.” As he has done at other points throughout the outbreak, DeSantis tried to tie the rise in cases to an increase in testing. Though testing has increased in Florida and across the United States, that increase does not explain growing case counts.

At the same time as he has cut funding for infectious disease treatment inside prisons, DeSantis has moved to stop the formerly incarcerated from voting in Florida. A court order in May said that people who had served time for a felony should be able to vote in Florida, but DeSantis is challenging that ruling. The challenge was filed shortly before the governor vetoed the $28 million allotted to infectious disease treatment inside prisons.

“He pivots to communities that are not only marginalized but potentially can’t vote,” said state Rep. Anna Eskamani, who has begun to garner talk as a potential Democratic rival to DeSantis in the 2022 gubernatorial race. “It such a dire situation,” she said of Florida’s prisons. “The bare minimum for the state is to ensure the safety of the incarcerated.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: