How the coronavirus undid Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There was the time Gov. Ron DeSantis showed up at a coronavirus press conference in a solitary rubber glove, proceeding to repeatedly touch his face with the other, ungloved hand. And there was the time he went through heroic struggles in trying to put on a respirator, its straps providing perhaps more of a challenge than they should have.

There was the time he said professional wrestling was an essential business, the time he blamed New Yorkers for the pandemic, the time he tried to stop cruise ships sick with COVID-19, the lung disease caused by the coronavirus, “dumped” on Florida’s shores.

Above all, there were confusing messages about what people should and should not do in response to the coronavirus.

Some people took the conflicting messages to mean that they should keep doing what they had been doing all along. Many went to beaches, where photographers were waiting. The images of crowded sands quickly went viral, and so now there was a Twitter hashtag to shame people flouting social distancing rules: #FloridaMorons.

Long before the coronavirus outbreak turned him into one of the least popular governors in the nation, Gov. DeSantis of Florida was something of a conservative golden boy.

He had spent barely a month at 700 North Adams Street in Tallahassee when talk began about when he might ponder a move to another, more coveted address: 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Having run as a Trumper, the 40-year-old governor quickly “shattered assumptions” about his ideological fealty, the Tampa Bay Times said, and, in doing so, had “drawn unexpected praise from Republicans and Democrats.”

Two years and two months later, DeSantis is not drawing much praise from anyone. Of the 15 governors whose approval ratings were recently tracked by polling site FiveThirtyEight, DeSantis was last. He was also the only governor of those 15 to see his popularity decrease because of the coronavirus. DeSantis’s approval rating dropped 7 percentage points, while California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s rose by 41 points.

And that was before DeSantis moved hastily to reopen beaches and other parts of Florida, an effort that appeared to be guided less by scientific thinking than a desire to please the White House, where the governor’s political benefactor resides. And it was before he was criticized for calling Florida “God’s waiting room,” a reference to the state’s elderly population that struck many as crass in the midst of a pandemic.

Florida has so far avoided the epidemiological disaster some worried was coming, but that appears to have happened despite DeSantis, not because of him. In fact, a 50-state survey by researchers at Northeastern, Harvard and Rutgers found that only 60 percent of Floridians approved of his pandemic response, 12 points below the national average.

Even so, DeSantis has moved quickly to deem the virus defeated. Last Wednesday, he announced that the state would begin partially reopening by the start of the following week. Deaths continue to climb in the state, but it is not exactly clear to what degree. Late last month, DeSantis’s administration told coroners to stop publishing coronavirus death data, making it impossible to know how many lives have been lost.

“We’ve got deaths stacking up in South Florida like crazy,” says Rick Wilson, a Republican consultant. The virus has killed 750 people in the three counties at the state’s southern tip (Broward, Miami-Dade and Palm Beach), which is three times more than have died from COVID-19 in all of South Korea. South Florida is exempt from the initial stage of DeSantis’s reopening plan, which begins on Monday.

Overall, the state has only tested 1.8 percent of its 22 million residents, according to a Miami Herald analysis. That means the state is declaring victory with almost no sense of enemy forces.

“It’s like we’re watching a mockumentary of a pandemic movie in Florida,” says Kevin Cate, a Democratic strategist in the state who worked for a Democratic opponent of DeSantis. In a post on Medium, Cate enumerated DeSantis’s many errors, from letting spring break revelers continue to congregate on Florida beaches to touting the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine, which some (the president foremost among them) held out as a potential coronavirus cure.

Cate charged DeSantis with a “disregard for the health of Floridians,” an especially fraught accusation in a state that already has the fourth-highest rate of uninsured individuals in the nation. It is also the state with the second-oldest population, after Maine. Already fragile, Florida has had its vulnerabilities vividly highlighted by DeSantis’s missteps.

DeSantis now has 33,000 coronavirus cases on his hands, and more than 1,200 deaths. What he no longer has is the confidence of his fellow Floridians, who were once poised to embrace him. A widely discussed Miami Herald editorial harshly criticized the governor, at a time when many other governors around the nation were being lauded for doing what the federal government could not or would not. “We’re looking like ‘Flori-duh’ again, Gov. DeSantis,” the editorial said. “Any idea how that happened?”

Especially surprising is the speed with which DeSantis has fallen out of grace. He appears to have squandered the unlikely bipartisan goodwill that marked his first term in office.

A virtually unknown congressman representing the Jacksonville suburbs throughout the second Obama term, DeSantis had become a Fox News staple by 2017, opining on Clinton-related conspiracy theories favored by Trump. Trump noticed, and when DeSantis ran against agriculture commissioner Adam Putnam in the Republican gubernatorial primary the following year, the president endorsed the largely untested young congressman.

In the general election, DeSantis ran against Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, who looked at the time like a rising Democratic star. DeSantis ran a Trumpian campaign, replete with racial innuendo (Gillum is African-American; Cate, the Democratic strategist, was a close Gillum adviser) and featuring an inflammatory television advertisement that had his toddler daughter building a border wall out of toy blocks. The Guardian accused him of “lapdog behavior.”

Whatever you wanted to call it, the ploy worked, with DeSantis narrowly defeating Gillum.

Victory seemed to transform DeSantis. He shed the trappings of Trumpism with what many saw as refreshing vigor, eager to show that he wasn’t the “lapdog” critics on the left accused him of being. The new governor quickly began working to restore the threatened wetlands of the Everglades, an issue far closer to Democratic hearts than to Republican ones. He named the state’s first chief science officer. He came out in support of cannabis legalization.

People were stunned, in particular Democrats who had seen their hopes of electing the state’s first African-American governor dashed.

“I say this as a Democrat and as a mayor: I’ve been really pleased and pleasantly surprised by the course and the decisions he’s made,” Tampa Mayor Bob Buckhorn told his hometown newspaper in 2019. An April 2019 poll gave him an approval rating of 62 percent among Floridians.

What happens in Florida rarely stays in Florida. As soon as DeSantis showed signs of political independence, he became the symbol of a post-Trumpian brand of Republicanism. “Ron DeSantis Is Showing the GOP a Different Path Forward,” went the headline of an Atlantic article from that January by Reihan Salam, a respected “non-Trumper” conservative. DeSantis even earned a favorable write-up in Mother Jones, the steadfastly progressive San Francisco-based magazine not known for favorable write-ups of Republicans unless they are named Abraham Lincoln.

For most of 2019, DeSantis managed to stay out of controversy, a generally impressive feat for any Floridian. So when, a year later, Politico compiled its list of 2024 — yes, 2024 — possible presidential contenders, DeSantis was on the list. “Remember when Republicans were so proud of their governors?” wondered the entry about his prospective run four years hence. Before Trump, the last Republican president was also a governor with Yale and Harvard degrees: George W. Bush.

The Politico article was published on Jan. 3. That same day, federal Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar called President Trump to warn him of a virus then devastating Hubei province in central China. By all accounts, Trump blew off the warning, and would continue to do so in the days and weeks to come.

That didn’t matter much to the pathogen. Throughout January and February, the virus spread along the West Coast, offering Eastern states a grim preview of things to come.

The first two cases in Florida were discovered on Feb. 29, just as thousands of colleges were about to descend on the state’s beaches for the beachfront bacchanal known as spring break. Debauched as the rite may be, it contributed a significant amount to Florida’s $14.4 billion annual haul from tourism-related taxes alone. Overall, the state, with its 663 beachfront miles, is third after California and Texas in tourism-related revenue.

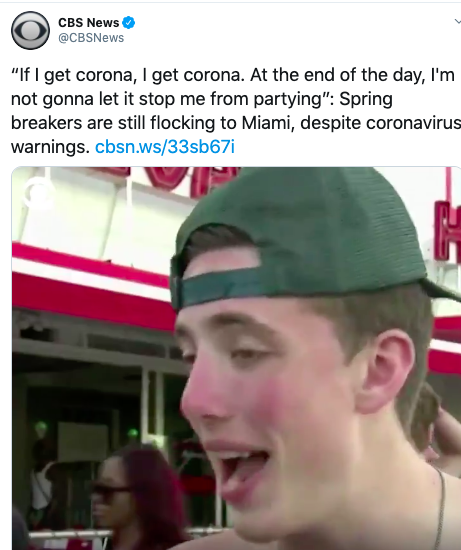

The spring breakers who’d booked their flights and hotels months before had no intention of staying away from Florida’s bars and beaches. Their attitude was best summarized by Brady Sluder, an Ohioan whose carefree assertion to CBS News — “If I get corona, I get corona. At the end of the day, I’m not gonna let it stop me from partying.”— went viral on March 18.

DeSantis was now in the midst of his first crisis, and he clearly didn’t know what to do. Republican governors like Mike DeWine of Ohio and Larry Hogan of Maryland had seen the threat coming, and they had acted without waiting for permission from Washington. That’s because they didn’t need it: DeWine and Hogan are experienced politicians who owe nothing to Trump. DeSantis, by contrast, owes Trump everything. Tweets from the president had made him, and they could just as easily unmake him.

DeSantis and other governors who’d been boosted by Trump — Brian Kemp of Georgia, Kristi Noem of South Dakota — now had an exceedingly difficult political challenge before them: They had to show their citizens they were moving to address the pandemic, but they had to make sure the measures they undertook did not anger the president, who had only started taking the virus seriously with great reluctance.

Not two weeks before, after all, the president had minimized the threat, tweeting on March 9: “Nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on. At this moment there are 546 confirmed cases of CoronaVirus, with 22 deaths. Think about that!”

The day after Sluder’s comments went viral, DeSantis defended his decision not to order a statewide closure of beaches. “They want you to social distance, of course,” he said on March 19 in describing a conversation with the U.S. surgeon general. “But they actually encourage people to get fresh air.” (DeSantis had closed restaurants and bars two days before; his education commissioner had closed schools the previous week.)

“Ron DeSantis is only here because of Trump,” argues Anna Eskamani, a progressive state legislator from the Orlando area who has been sharply critical of DeSantis. “He won’t move on things unless Trump gives him permission to.”

As the crisis deepened, DeSantis remained in regular conversation with the White House, speaking frequently with the president or officials on the coronavirus task force. The White House would not elaborate on communications between the two men. “President Trump speaks often with many governors, including the Florida governor,” said White House deputy press secretary Judd Deere in an email to Yahoo News.

Continuing to seek guidance was a mistake, says Wilson, the Florida-based Republican consultant who has emerged as one of the most prominent anti-Trump voices in the conservative movement. “He doesn’t understand that Donald Trump is a huge drag on his ability to be a leader,” Wilson told Yahoo News.

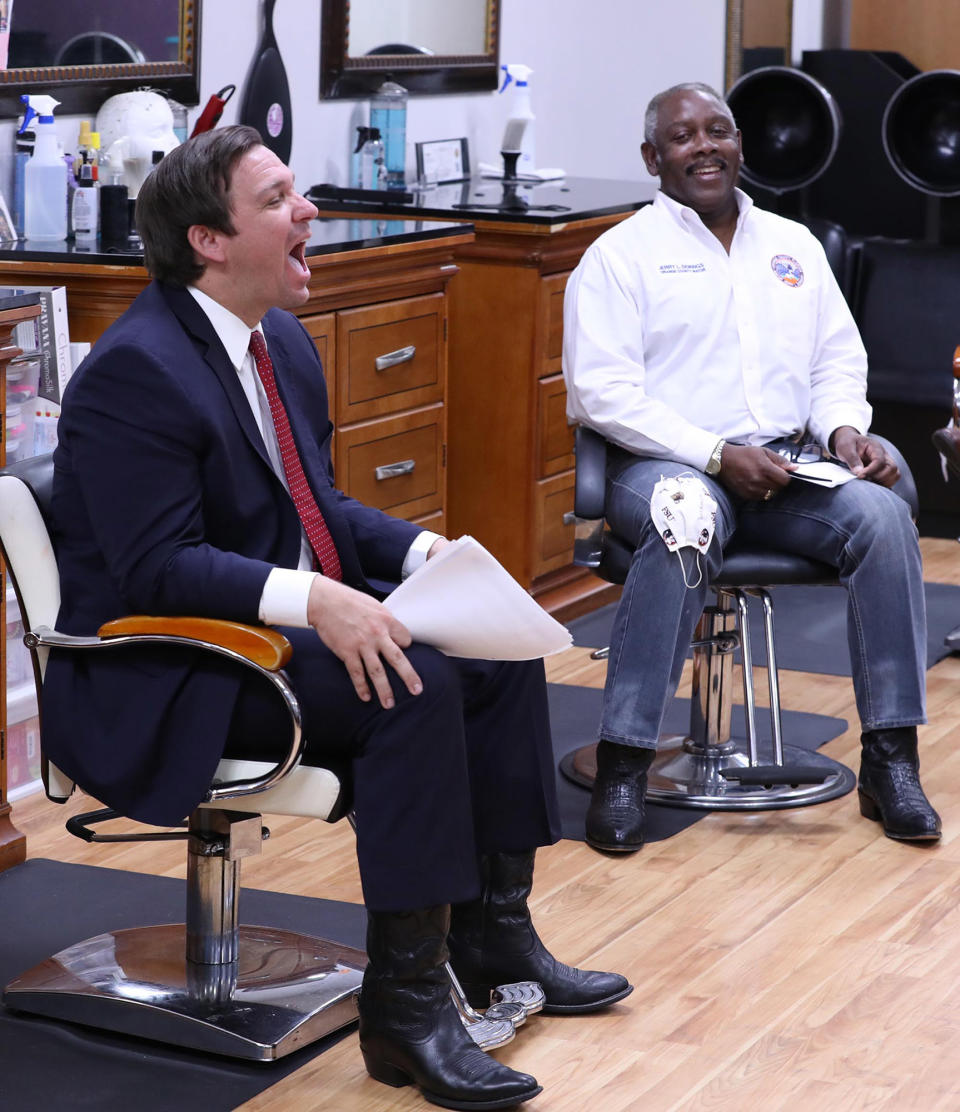

Even as he continued to seek counsel from the White House, DeSantis made no effort to communicate directly with the mayors of Florida’s biggest cities. If those mayors happened to be Democrats, they were flatly ignored by the governor, according to what those mayors or their press secretaries told Yahoo News about their interactions with DeSantis between mid-March and mid-April.

“The governor and the mayor have not spoken directly,” said Cassandra Anne Lafser, spokesperson for Buddy Dyer, the mayor of Orlando, a city of 286,000 residents. DeSantis also neglected to reach out to Rick Kriseman of St. Petersburg (pop.: 265,000). DeSantis and Jane Castor, the mayor of Tampa (pop.: 393,000) have also not spoken throughout the coronavirus crisis.

Castor told Yahoo News that she was speaking “regularly” with Jared Moskowitz, the well-regarded head of the state’s Division of Emergency Management. Castor said that she was also in regular communication with her fellow Florida mayors, as well as mayors from around the country. In a phone conversation with Yahoo News, the former police chief was careful not to criticize DeSantis, but the governor didn’t appear to factor into her coronavirus response.

Republican mayors have had better luck getting the governor’s attention. A spokesperson for Francis Suarez, the mayor of Miami — the state’s second-largest city, with a population of 471,000 — had spoken to DeSantis “around three or four times” between mid-March and mid-April. Lenny Curry, the mayor of Jacksonville (pop.: 904,000), fared even better when it came to gubernatorial communication. “Mayor Curry speaks frequently with Gov. DeSantis,” said Nikki Kimbleton, a Jacksonville spokesperson.

The governor’s press strategy also seems to have been borrowed wholesale from the president, which isn’t especially surprising, since his communications director Helen Aguirre Ferré is an alumna of the Trump administration. Preparing to enter a gubernatorial briefing in late March, journalist Mary Ellen Klas — a bureau chief for both the Tampa Bay Times and Miami Herald — found her access blocked. She later said, according to the Miami Herald, that “the state was refusing her access into the Capitol because she had requested ‘social distancing’ at the governor’s briefings.”

The very concept of social distancing seemed to offend DeSantis. On April 13, state Surgeon General Scott Rivkees said in a Cabinet meeting that social distancing would have to continue until the development of a coronavirus vaccine. While that assertion appeared to be thoroughly innocuous from a scientific perspective, it appeared to offend DeSantis. Ferré made Rivkees leave the meeting.

DeSantis was obviously concerned with not contravening Trump, determined to only do something after the president had done it first. Even as much of the country went into lockdown, DeSantis refrained from doing so. Instead, he blamed New Yorkers for bringing the disease to Florida, ordering that people flying in from the New York City metropolitan area be quarantined for two weeks upon entering Florida.

DeSantis said that the White House was worried about people “fleeing the hot zone and bringing the virus to Florida.” This dubious thinking was in line with Trump, who considered — but ultimately decided against— a mandatory quarantine for the city. An analysis of flight and coronavirus data by local news affiliate WFLA later found that only 6 percent of the state’s cases had originated in New York.

Asked several days later why he refused to issue a statewide lockdown order, DeSantis said he was awaiting word from the White House. “I’m in contact with them and basically I’ve said, ‘Are you guys recommending this?’ The task force has not recommended that to me. If they do, obviously that would be something that would carry a lot of weight with me.”

On March 28, the White House extended its own stay-at-home guidance for another month. This did carry weight with DeSantis, who promptly issued a 30-day stay-at-home order of his own. DeSantis did little to explain how the state order would work within the context of local or county orders that in some cases had been in place for several weeks. “There was a great deal of confusion” about the state order, Castor, the Tampa mayor, told Yahoo News.

That order also became the subject of national mockery when, about two weeks after first issuing it, DeSantis amended the order so that professional wrestling was now deemed an “essential business.”

New troubles loomed. Images of packed beaches were now replaced by another: that of people waiting in seemingly endless lines to apply for unemployment benefits through the state’s Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, which was to be administered by the state’s employment department.

The unemployment site had been created by DeSantis’s predecessor, Rick Scott, now a member of the U.S. Senate. But its deficiencies were not exactly a secret. An audit performed in 2015 had found many problems with the site, as did a follow-up audit conducted in 2016. DeSantis took no evident steps to correct the problems after taking office.

Floridians desperate for relief don’t care much about who was originally at fault. Anna Wallace lives in Lake Worth, not far from the president’s Mar-a-Lago resort, and was laid off from her job as a customer service representative on March 23. She has been struggling with the state’s unemployment system ever since. It took a month for that system to declare her ineligible, for reasons that are beyond her.

“I can’t get through to anybody,” she told Yahoo News. She has emailed DeSantis and tweeted at him, to no evident effect. And though she is eager to get back to work, she is worried that DeSantis is moving too quickly.

“I don't agree with it, to a certain extent,” she told Yahoo News of the governor’s rush to reopen. “Who doesn’t wanna make money? But at what cost?”

Wallace added that, in her view, DeSantis is a “follower.”

Much like Trump, he has been impatient to get the pandemic over with. He spent much of April promoting the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine as a potential cure, but when Trump stopped boosting its benefits, so did DeSantis. Hydroxychloroquine has since been shown to be potentially harmful to coronavirus patients.

Then he said that, despite a lack of treatments and vaccines, it was time to reopen the state anyway. Less than two weeks into his lockdown, DeSantis suggested it was time to resume public education. “I don’t think nationwide there’s been a single fatality under 25,” the governor said, an incorrect assertion. His proposal to reopen schools earned a rebuke from Dr. Anthony Fauci, the National Institutes of Health epidemiologist and a prominent member of the president’s coronavirus task force.

Florida’s schools remained closed, but not its beaches. DeSantis announced on April 17 that beaches could begin to reopen. Among the first to take up the call was Curry, the Republican mayor of Jacksonville who has worked closely with DeSantis throughout the pandemic.

Florida is a large, complex state, which has made governing in the midst of a pandemic exceptionally difficult. That difficulty has been exacerbated by DeSantis’s acute awareness that he cannot contravene Trump. “It’s a tightrope to walk,” acknowledges Chip LaMarca, a Republican state representative from the Fort Lauderdale region.

“I would give the governor an A,’’ LaMarca told Yahoo News, disputing suggestions that the governor’s response has been faltering and haphazard. “We’re trying to do this in a measured approach,” he argued.

And even Cate, the Democratic strategist, credits DeSantis with some decisions, including the April 2 declaration that evictions and foreclosures would be suspended for 45 days.

Floridians, however, are growing increasingly dissatisfied. A new poll, conducted throughout April, finds that while 69 percent of Americans approve of the job their governors are doing in battling the coronavirus, only 51 percent of DeSantis’s constituents endorse his handling of the pandemic. That puts him in unwelcome company with Kemp, the Georgia governor whose hasty reopening plan earned sharp criticism from Trump himself.

With its 29 Electoral College votes, Florida will be enormously consequential in next fall’s presidential election. Trump knows that, of course. He is a Florida resident himself, having switched his primary residence from his Fifth Avenue tower in Manhattan to his Mar-a-Lago golf resort in Palm Beach. He also knows that if Floridians are angry at DeSantis, they are likely to take that anger out on the Republican Party’s head, potentially handing the crucial state to the presumed Democratic nominee Joe Biden.

“We had many Republicans tell us they will never vote Republican again,” says Eskamani, the Democratic state legislator.

That explains why Trump invited DeSantis to the White House last week. DeSantis trotted out charts to show that, in fact, Florida was defeating the disease. Later that evening, DeSantis was on Sean Hannity’s primetime Fox News program, yet another sign that he was in desperate need of positive press.

Hannity, who acts like a shadow press secretary and chief of staff to Trump, praised DeSantis, who the anchor said took “very aggressive steps right away” to keep Florida safe. “You saved a lot of lives,” Hannity told the embattled governor.

The notion, purveyed eagerly by Hannity, that DeSantis has successfully defeated the coronavirus is false. While the spread of the disease has slowed, little DeSantis has done could be seen as leading to that outcome.

As for the goodwill DeSantis engendered in his first year, it is gone. Buckhorn, the erstwhile Tampa mayor who praised DeSantis in 2019, is certainly not praising him anymore. “I’ve been disappointed,” Buckhorn told Yahoo News. DeSantis, he worries, is “reverting to what our worst fears were.”

_____

Click here for the latest coronavirus news and updates. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please refer to the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.

Read more: