Meet the woman who helped desegregate Cincinnati’s streetcar system

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Let me introduce you to the Fossetts, one of Cincinnati’s most influential couples.

Nearly a century before Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Sarah Mayrant Walker Fossett took a stand and helped desegregate Cincinnati’s streetcar system.

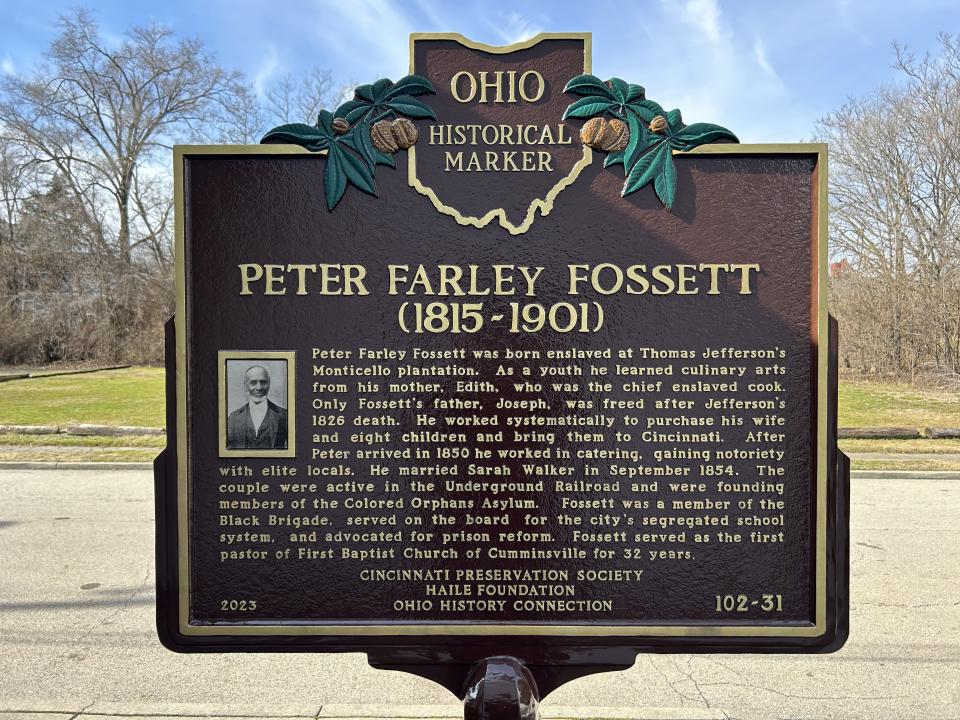

Her husband, Peter Farley Fossett, was a pastor, a member of an elite catering family and secretly a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

The couple were among the most prominent Black citizens in Cincinnati before, during and after the Civil War. And they are getting their due at long last.

In December, an Ohio historical marker for the Fossetts was placed outside the First Baptist Church at 3640 Roll Ave. in South Cumminsville, the church the couple founded in 1870.

Between them there is so much history that Sarah’s story is told on one side of the marker, Peter’s on the other.

Black history: ‘Amplifying the voices of those muted by history’: Challenges of researching Black history

Getting to know Sarah Fossett

Sarah Fossett’s role as a civil rights pioneer is a tale that needs to be told.

Sarah was one of the historic Cincinnati women my wife, Kristin Suess, and I featured in our “10 ___ Women” project back in 2019. Our goal was to bring a spotlight to some of the overlooked or forgotten women in our history. We are so delighted Sarah Fossett is getting more attention with the historical marker.

Not much is known about her early life. According to a brief profile in “Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens” by Wendell P. Dabney, published in 1926, Sarah was born June 26, 1826, to Rufus and Judith Mayrant, in Charleston, South Carolina. She was likely born into slavery, but there is no information on how she was freed.

At an early age, she was sent to New Orleans to study under a French specialist in scalp and hair care, training which made her a skilled hair stylist.

She was brought to Cincinnati about 1840 in the care of Abraham Evans Gwynne, part of a wealthy Cincinnati family. (His daughter, Alice Claypoole Gwynne Vanderbilt, wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, had the Gwynne Building at 602 Main St. built and named in her father’s honor.)

Through the Gwynne family’s connections, Sarah found the opportunity to be a sought-after hair stylist to Cincinnati’s society women.

Sarah also was known to be a close associate of Levi Coffin, the white leader of the Underground Railroad that was secretly assisting enslaved people in Kentucky to escape to freedom.

In 1854, she married Peter Fossett, who was also an operative with the Underground Railroad.

Thomas Jefferson’s house servant to Underground Railroad conductor

Peter’s story was the subject of a column a few years back.

Born into slavery in 1816 as a house servant at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, he recalled as a child visits by James Madison, James Monroe and Marquis de Lafayette.

“I had nice house servant work, got tips and all that sort of thing,” Fossett recalled during a lecture at Ninth Street Baptist Church in 1898. “Suddenly, at the death of my old master, Thomas Jefferson, I was put on the auction block and sold for $500 to strangers.”

When Jefferson died in 1826, he freed only five people in his will, including Peter’s father, who was able to buy his wife and five of Peter's siblings. Peter was sold and ran away. Recaptured, he was then sold to friends who sent him to his family who had relocated to Cincinnati.

He joined the family’s catering business (his mother, Edith, is credited with bringing Jefferson’s favorite French cuisine to Cincinnati), while secretly operating as a conductor with the Underground Railroad.

During the Civil War, Fossett served as a captain in the Black Brigade that helped protect Cincinnati under siege by Confederate forces in September 1862.

Taking a stand and refusing to leave

Prior to the war, before the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, Sarah Fossett fought her own battle for racial freedom.

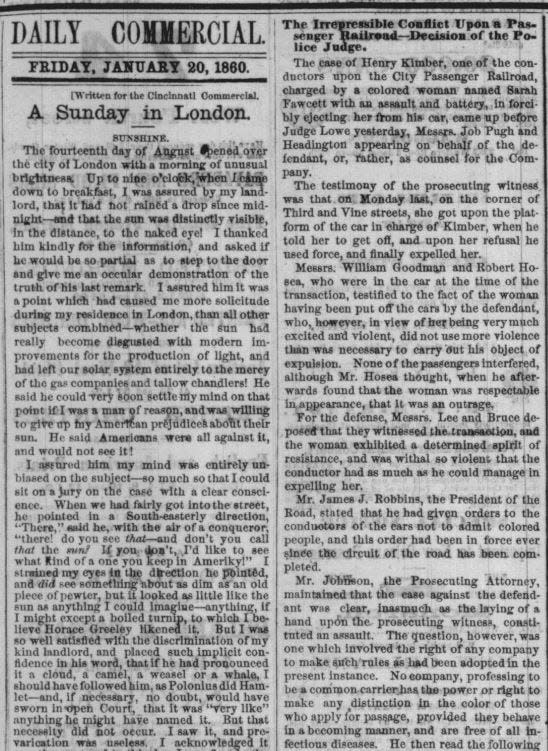

On Monday, Jan. 16, 1860, she stepped on a platform to board a Cincinnati streetcar operated by the City Passenger Railroad Co. The white conductor ordered her to leave, but she refused, claiming her right to ride in the streetcar. He then “forcibly ejected her from the car,” according to the legal case reported in “Weekly Law Gazette.”

Sarah had the conductor, Henry Kimber, charged with assault and battery.

The case went before the Police Court a few days later. The Cincinnati Gazette and the Cincinnati Commercial both reported on the case Jan. 20. (No mention was found in The Enquirer.) Sarah’s name was misspelled Fawcett in the court reports and newspaper stories.

The Gazette reported that Sarah “testified that she hailed the car on Third street, opposite the Burnet House, when the Conductor stopped for her, and said she could not ride. She told him that it was her impression that it was a public conveyance, and that she was not committing any offense. Conductor then commenced beating her across the breast and shoulders; still she held on to the car and refused to get off. Conductor then told the driver to go ahead. When the cars had proceeded a square or so the Conductor pushed her off.”

James J. Robbins, president of City Passenger Railroad, testified that he had given orders to the conductors not to admit “colored people” on the streetcars, although that was not in the company’s official printed rules.

Defense lawyers argued “the case was one which had been got up expressly for the occasion, wherein a woman was thrust forward by a combination of colored people, who were then in Court, to test the right of the company to exclude them from the cars,” the Commercial reported.

Judge David P. Lowe ruled in favor of Fossett.

Judge Lowe stated, “It is not pretended that the passenger was in any way disorderly, that she refused to pay her fare, that there was any lack of room for her accommodation, that any of the passengers objected to her being received, or that there was any objection to her whatever but her complexion.”

He found that the actions to remove her were assault and battery but not malicious. He fined Kilmer $10 plus costs (that’d be $344 today).

Sarah filed a civil suit, and according to Sean E. Andres on the Queens of Queen City blog, she was awarded $65 ($2,017 today) for being refused a ride, but no damages.

Sarah’s case did desegregate the city’s streetcars for Black womaen and children. Black men, though, had to wait until Isaac Young won the judgement in a similar case in 1866, after he and his wife were forcibly removed from the Cincinnati Streetcar Co. line.

Judge Bellamy Storer – who, as the former law partner of Abraham Gwynne, would have known Sarah and her case – awarded Young $800 ($17,000 today) in damages and desegregated the streetcars fully.

Fossetts appreciated for their philanthropic work

The Fossetts were both known for their philanthropic work in later years. As a newly ordained minister, Peter founded First Baptist Church in 1870 and served as pastor for the next 31 years for no pay, while he and his wife paid off the church’s debts.

Sarah was particularly active with the Orphan Asylum for Colored Youth and was elected manager, serving in that role for nearly 25 years.

Peter Fossett died in 1901. Sarah died in 1906. They were both buried in Union Baptist Cemetery in Price Hill, the oldest Black cemetery in Hamilton County.

The Fossetts stood up and refused to give in, proof of what effect one or two people can have on the world around them.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Black history: This woman helped desegregate Cincinnati’s streetcar