Structural cascade: Broken rods were just a symptom of RI's Washington Bridge crisis

A couple of broken bridge parts took center stage when the Rhode Island Department of Transportation closed the westbound lanes of the Washington Bridge in December, citing the potential for a catastrophe.

RIDOT Director Peter Alviti Jr. asserted that the highly disruptive shutdown was due in part to the span’s broken tie-down rods, which he referred to as “pins.”

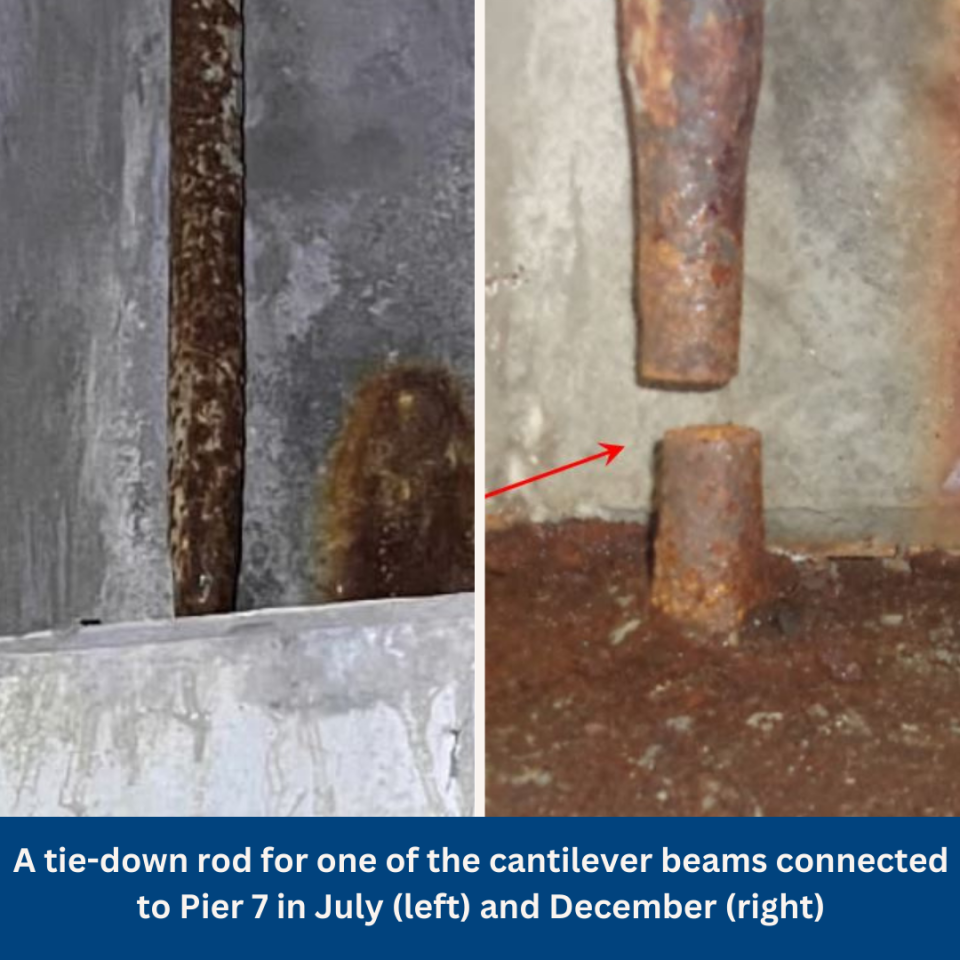

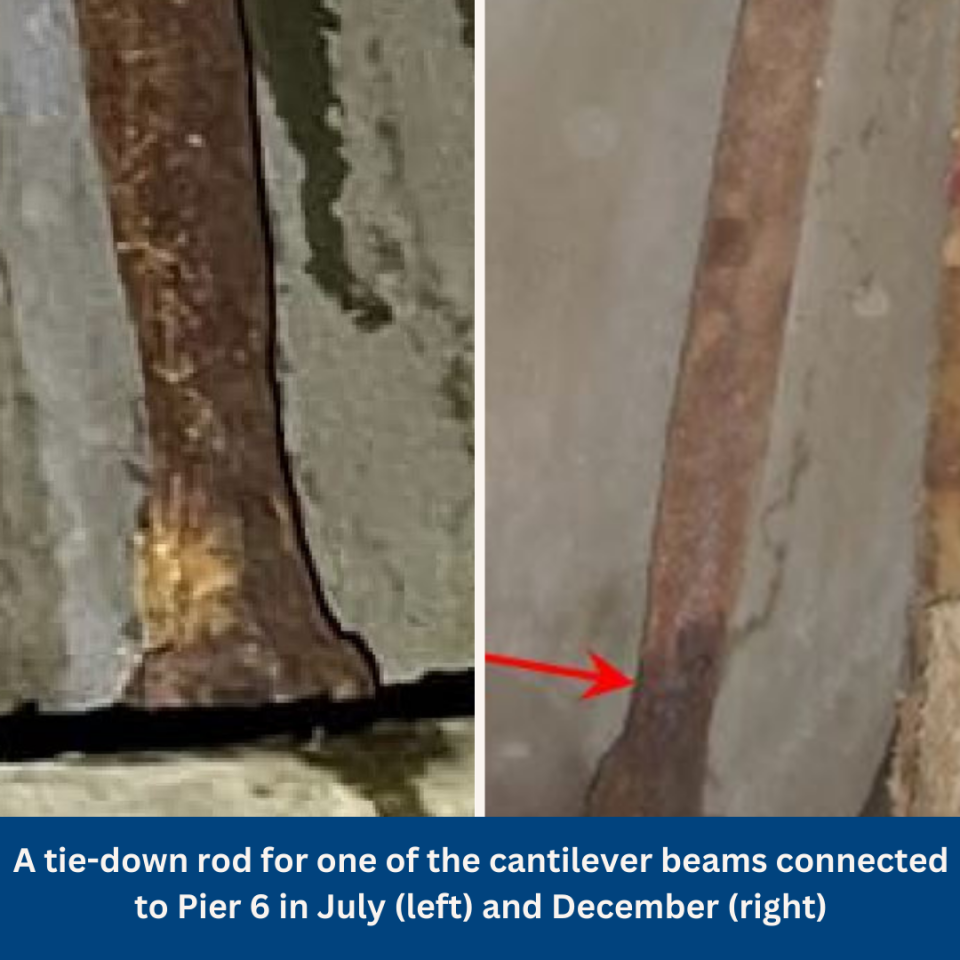

Alviti cited a “cascade” of other related “deficiencies.” But the rods, shown in photos provided by RIDOT, would draw heavy public scrutiny initially.

Two were broken. And both exhibited another trait: Neither was uniform in diameter. Each was narrower in the area where it was broken – as if something had stretched it.

Also, the diameter of a third rod that was tapered but not broken had drawn attention from an inspector. The rod’s diameter was measured at 1 inch, according to a notation with a photo that DOT posted online. That's almost half an inch less than the diameter specified in the bridge's plans.

More than two months later, other structural concerns are emerging. But the bridge’s tie-down rods remain prominent, and questions about them remain unanswered.

Why did the rods break? How long were they broken before the shutdown? Was their narrowing a warning sign? If so, why didn’t DOT close the bridge before they broke rather than after?Could the failure of just a few rods leave the bridge vulnerable to a potential catastrophe?

Oversight hearing with Alviti and engineer raises more questions

At an oversight hearing at the State House last week, Alviti provided some additional context, acknowledging, for example, that some rods had showed narrowing under tension, something engineers refer to as “necking.”

Alviti also emphasized that the U.S. Department of Justice is tracking the history of the rods “to see what happened.”

Initially, an engineer whose company works for DOT, Jeffrey Klein, gave his take on how the bridge works. It included some points about the role of the tie-down rods.

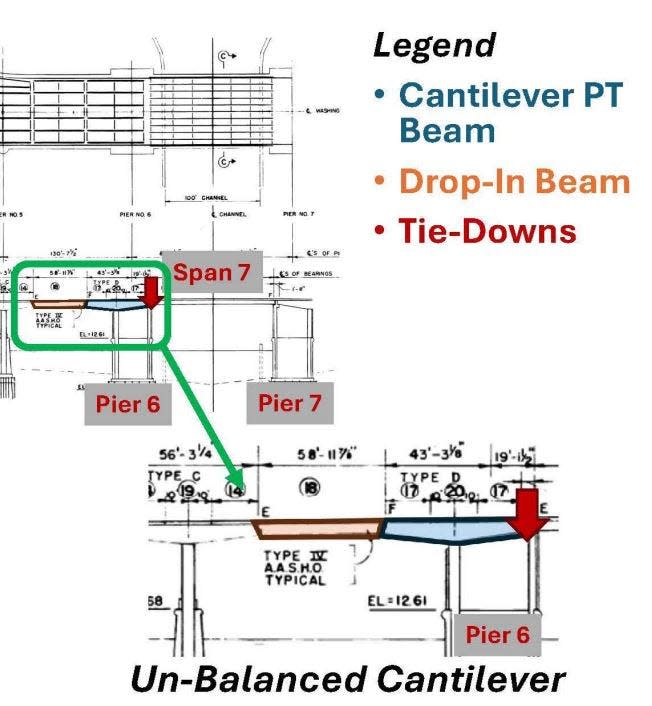

Bridges are frequently described as spans, but the crossing that takes westbound Interstate 195 traffic over the Seekonk River is not a single span. It is a series of spans supported by abutments, which rise out of the water below.

Some spans rely on the tie-down rods to provide stability, according to Klein, who drew attention to a specific drawing in DOT’s PowerPoint presentation.

One drawing in the display offers a side view, showing both a large bridge abutment and a single span. One side of the span is above the abutment while the other side is above the water.

That abutment side of the span has steel rods that tie it down to that structure, according to Klein's presentation.

With this "cantilever" design, the end of the span that protrudes out over the water can support the next bridge section in the series without any abutment directly beneath it.

The "span" in the drawing that Klein referenced looks like a single part. But it represents six parallel beams.

The beams, which engineers also refer to as cantilever girders, are massive structural components. Each concrete beam is held down by two tie-down rods.

Klein told lawmakers that the particular spans with tie-rods are held down by a total of 12 rods. Ten of those rods are encased within the concrete bridge abutments below. The other two rods are mostly exposed.

During the oversight hearing, Alviti said he still hasn’t determined when the rods broke, “Part of the work we're having done right now is for a forensic engineering company to determine when those pins actually broke,” he said, adding that samples of material from the rods are part of the analysis.

“That will tell us how far back the inspection reports were either correct or incorrect,” Alviti said. “When we have that .... we'll be looking at all of the responsibility issues that go with that.”

Another question: Is it clear now that a thorough inspection in July would have included a look at the tie-down rods?

Alviti said it was “always our opinion” that the companies inspecting the bridge had the responsibility of reporting “any concern” about the structural integrity of the rods as well as the rest of the structure.

Alviti said the visible narrowing of rods didn't happen between July and December 2023.

“No, I don’t think so,” he said. “I think the necking showed up in previous reports, but it never rose to the level of concern, of being a critical finding.”

Deformation in steel rods

“Necking” is a specific engineering term. It refers to one way that a steel rod can fail under tension.

A portion of the overloaded rod visibly narrows like a stretched rubber band. The rod basically loses elasticity. Finally, it breaks.

Necking is not an obscure subject in the engineering world; undergraduates study it in college, according to professor Barzin Mobasher of Arizona State University.

The photographs of the narrowed rods on the Washington Bridge are “textbook” exhibits of necking, he says.

In the July photos, the rods were stressed and stretched way beyond allowable engineering design, he says. And even at that point, before the rods were visibly broken, the necking was sufficient evidence of failure, he says.

“That’s enough,” says Mobasher.

Mobasher and another engineering professor, Andrew Bechtel of The College of New Jersey, were asked to provide comment on the rods following last week's hearing.

“It makes me shiver to think,” says Mobasher, “that somebody can just dismiss that, ‘Oh this is just a reduction in section.' No. I feel comfortable saying we would never even contemplate dismissing something of that nature.”

“Let’s not whitewash the necking issue,” he says. “The necking issue – in my opinion, it’s like the spaceship Challenger – the O-ring. That’s what it is.” This is a reference to NASA's dismissal of concerns about seals in one of the solid-fuel rocket boosters during the run-up to the 1986 shuttle disaster.

As questions about public safety and tie-down rods percolate, it's tempting to wonder if anything less than the most agile response to necked tie-down rods on such an old bridge is tantamount to a major fumble by the bridge's overseers. The professors' comments do not squelch that train of thought. But neither professor is ready to blame the DOT for a major inspection failure.

The bridge’s 1960s design incorporates elements that today’s inspectors aren’t likely to be familiar with, including the bridge’s exposed tie-rods, according to Bechtel. He says the necking of such tie-rods in a bridge isn’t something a typical inspector is likely to notice or focus on.

Bechtel compares the unusual presence of external tie-rods on the bridge to an organ that a doctor has never seen before.

“We train the inspectors to be like doctors, assuming that people all have the same kind of parts,” says Bechtel. “This is not a common part.”

If RIDOT knew about necking, should the department have acted sooner?

Mobasher's O-ring comparison is pointed, but he also credits the bridge's inspectors for gathering the information in the first place and he emphasizes that he isn't "upset" with how DOT has come to terms with the situation.

He likens the process to skimming the surface and then digging deeper.

“If you find more evidence, it’s you’re duty to come to the public,” he says. “That’s the credit that I give them,” he adds.

He also says the physical role of the tie-rods in the bridge was “minor” if the structure was functioning the way it was designed to function.

The necking of the rods, he says, was evidence of other, bigger problems on the bridge.

Images from July show cracks and gaps and the movement of some bridge components that are massive in size and weight, Mobasher says.

The observable gaps include space between the broken ends of the tie-rods themselves. All of this indicates movement of major components that wasn’t intended by the bridge’s design, Mobasher says.

Too much load, he says, was transferred onto the rods.

Such movement, even a fraction of an inch, can “snap a tie-bar like a pretzel,” he says.

“The fundamental insight,” Mobasher says, “is the integrity of bridge cannot be realistically dependent on the functioning of a single tie-down … as the forces we are talking about are hundreds of times higher than the capacity of a tie-down.”

Bechtel also sees major issues with the overall condition of the bridge.

“I think the real thing is, this bridge should have been replaced a while ago,” he says.

Mobasher and Bechtel emphasized the limited nature of their own knowledge about the bridge itself. They offered their reactions to the situation after quickly looking at bridge drawings and photos. This was before the dissemination of a consultant's report on Thursday.

'Read the drawings,' says DOT critic Rob Cote

One of the most outspoken local observers of the bridge's engineering issues is Warwick resident Rob Cote, who has made waves around the state for years by voicing criticisms of government officials and workers, particularly in Warwick.

Following Alviti’s comments at the hearing, Cote was highly critical.

Cote, a certified structural inspector who inspects a lot of bridges, sees huge problems overall with the bridge – not just the rods. But he’s ready to cite the DOT for being too slow to deal with deficient rods.

“If that is true, as evidenced by their own photos, why wasn’t the bridge load restricted?” Cote asks.

Cote also says the DOT and its bridge inspectors are responsible for uncommon elements such as tie-down rods.

“You read the drawings,” he said.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Washington Bridge tie-down rods: Symptom of structural cascade?