Polarizing predator: Separating fact from fiction to answer common questions about wolves

When it comes to Coloradans' feelings about wolves, there is little gray and lots of black and white.

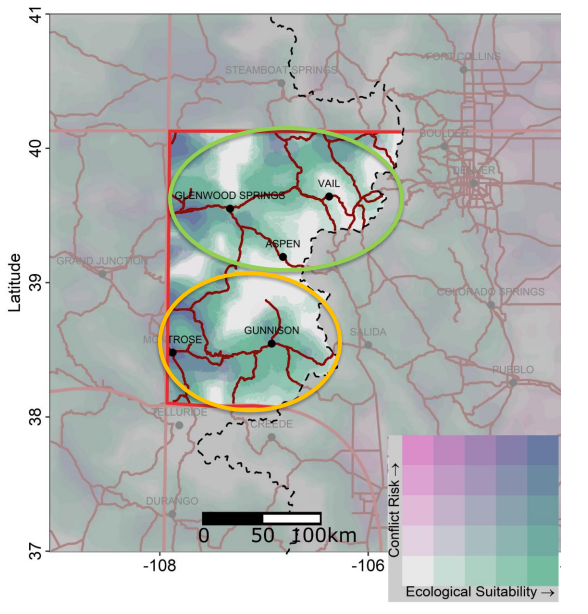

Those polarizing feelings have been stoked since Colorado Parks and Wildlife released 10 wolves into Grand and Summit counties in late December. They were the first to be released under the state's wolf recovery plan, which calls for 30 to 50 wolves total to be released over the next three to five years.

Wolf advocates say wolves belong back on the landscape and will offer wildlife viewing opportunities and tourism revenues. They also point to how reintroduced wolves restored the ecology of Yellowstone National Park and say they will do the same in Colorado.

Ranchers claim wolves could put them out of business, and hunting outfitters say the apex predator will decimate the lucrative deer and elk hunting industry in the state. Others fear wolves are a threat not only to livestock but people and pets as well.

There is some truth to those ideas, but the polarization also inherently perpetuates half-truths.

One thing is for certain: Wolves are back in Colorado — and maybe this time for good, after largely being extirpated from the state in the mid-1940s.

There are studies to support claims by both sides of the wolf aisle, but here are answers to common questions about wolves that separate fact from fiction based on the most accepted science.

Two entities that include those studies on their websites are Colorado Parks and Wildlife and CSU's Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence.

How are the recently released wolves doing in Colorado?

Colorado Parks and Wildlife said as of the first month after the release, all the wolves are still alive and in Colorado and none had a reported livestock depredation.

Some have stayed in the general area of the release sites, and some have moved northwest into south Routt County. One of the first photos of the released wolves by the public was taken about 5 miles from the first release site.

Then why did the reintroduction cause such a stir among some?

The released wolves are the beginning of what the state wolf recovery plan hopes will lead to a sustainable population of a minimum 150 to 200 wolves. That plan, which many viewed as a success, started three years ago, so the release in late December didn't come as a surprise.

What angered mostly ranchers, outfitters and rural folks on the Western Slope was the way the release was handled by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

State wildlife agency leadership said the release needed to be done in as much secrecy as possible for the safety of the wolves and the people doing the release. Those people numbered about 45 and included Colorado Parks and Wildlife staff, wolf advocates and Gov. Jared Polis, who pushed for the reintroduction deadline to be moved up from 2023 to 2022 after the measure was passed. That idea was rebuffed by the Colorado Wildlife Commission.

The Colorado Wildlife Commission, which voted on the recovery play, was not informed of the release until after it happened, which upset some members.

That anger spilled over to some state and county government leaders and ranchers whose land was near the release sites and weren't told about the release.

What further exacerbated the situation was Colorado Parks and Wildlife capturing wolves from northeast Oregon packs with a recent history of depredation of livestock and the belief those wolves will kill or injure livestock in Colorado.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife leadership has apologized for not making it clear they would capture wolves with prior depredation history and have vowed to work on its communication with affected ranchers.

They also said they are working on a program that will allow the public to see areas where the wolves are present and inform livestock producers of the wolves' whereabouts to allow them to take precautions.

However, ranchers and hunting outfitters say a lack of transparency and communication from Colorado Parks and Wildlife has strained their relationship and that it will take time to regain trust in the agency.

Why is Colorado reintroducing wolves when they are already here?

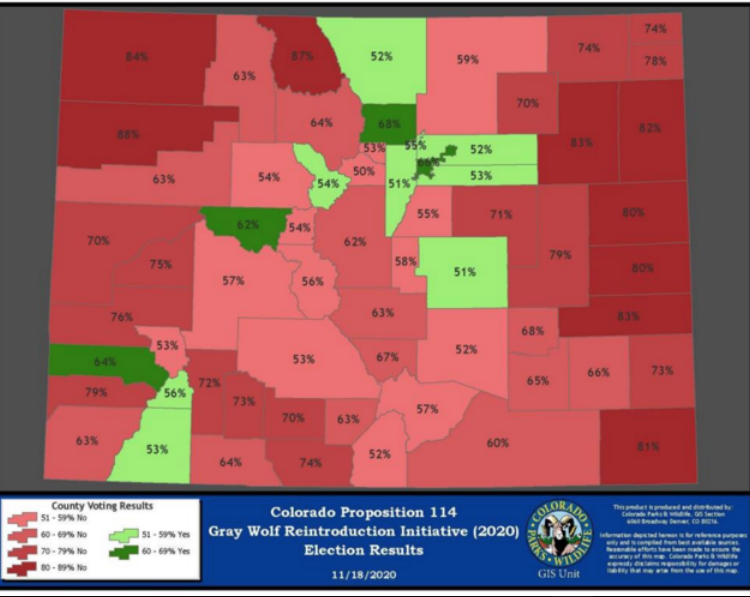

Quick answer: Voters approved a ballot initiative in 2020 that mandated gray wolves be reintroduced west of the Continental Divide starting by the end of 2023. The measure was the first of its kind passed by a state in the U.S., and it passed with 51% of the vote.

An explanation: The vote was a sharp divide between urban and rural counties. Only 13 of 64 counties voted in favor of reintroduction, but the bulk of those favoring the measure were heavily populated Front Range counties that include Fort Collins, Boulder, Denver and Colorado Springs.

Only five western counties where wolves can be released voted in favor of the measure. Those counties include the municipalities of Breckenridge, Aspen, Telluride and Durango.

Digging deeper: There have been infrequent sightings of wolves in Colorado for decades, but some groups wanted to speed up the process to restore wolves to a sustainable level through reintroduction, like what had been done in Yellowstone National Park and Idaho in the mid-1990s.

Points to consider:

Wolf populations in Yellowstone and Idaho reached initial recovery goals three years after reintroduction but it wasn't until 2002 that those goals were reached for three consecutive years, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

In 2020, a pack was found in Moffat County in the far northwest corner of Colorado. The Moffat County pack disappeared a year later.

In spring 2021, two wolves that naturally migrated into Colorado from Wyoming gave birth to six pups in Jackson County, the first born in Colorado in 80 years. Those were known as the North Park pack, which now numbers just two.

Many of those wolves from both packs were legally shot in Wyoming.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife says the state is home to the 10 recently released wolves and two from the North Park pack in Jackson County that have GPS radio collars. Ranchers claim there are more.

Will wolves kill a lot of cattle and sheep in Colorado?

Quick answer: This is mostly a myth. Considering the overall number of cattle and sheep where wolves are/will be present in Colorado, there will be minimal impact. But impacts can and have been significant to certain ranches in certain areas in Colorado and elsewhere.

Digging deeper: In the West, the percentage loss of livestock to wolves is somewhere in the low single digits or lower when you factor in only cattle on farms and ranches where wolves exist and don't include cattle in feedlots, which have minimal risk.

Points to consider:

Studies in Montana show about 17% of wolfpacks kill livestock.

In northeast Oregon, where Colorado captured and relocated wolves for its reintroduction program, Oregon Department of Game and Fish records show 13 of 29 packs (45%) have confirmed depredations since July 1, 2023. Five of the 10 released wolves were from packs that had depredated livestock in Oregon in the last six months.

Studies have shown once wolves learn to kill livestock, they have a propensity to continue the behavior, which worries Colorado livestock growers.

Members of the North Park pack have been confirmed by the state wildlife agency to be responsible for killing or injuring 20 livestock, including 14 cattle, three sheep and three working cattle dogs over the last two years across six ranches in Jackson County. Seven of those livestock killed have been on a ranch leased by Don Gittleson north of Walden.

Studies after wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone and Idaho show the number of times wolves killed or injured livestock steadily increased for several years until the wolf population stabilized, then livestock depredations declined.

Will wolves wipe out Colorado's deer and elk herds?

Quick answer: This is mostly a myth. Like in the livestock industry, wolves are unlikely to have a major impact on overall deer, elk and moose populations or hunting opportunities in Colorado at a statewide level, but populations may be impacted in certain areas.

Digging deeper: There is much information spread that wolves have decimated deer and elk herds and hunting opportunities in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho since wolves were reintroduced into Idaho and Yellowstone in the mid-1990s. The concern is that will happen in Colorado.

Points to consider:

Elk are the primary prey base of wolves in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho. Despite an increase in wolves, the elk population and number of elk killed during hunting season have not declined since wolves were reintroduced in 1995 to 2018.

Colorado has an abundant prey base for wolves. The state's elk herd of around 280,000 is the largest population of any state, and the vast majority of its 430,000 mule deer are found in western Colorado where wolves are being reintroduced.

In pockets, wolves, along with other factors including severe winters and habitat degradation, have reduced the number of elk in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho and could do the same in Colorado.

According to the Colorado Wildlife Council, in 2018, hunting brought in $834 million into the state, the vast majority of which comes from deer, elk and moose hunting licenses and spending by those hunters.

What threat do wolves pose to people and their pets?

Quick answer: Wolves pose virtually no risk to humans but some risk to dogs.

Digging deeper: Since 1900, there have been no reported fatal human attacks by wolves in the lower 48 states and one fatal attack in Alaska in 2010. Since 2002, there has been one nonfatal wolf attack of a human in the lower 48 states, which happened in Minnesota in 2013.

Points to consider:

Wolves are generally afraid of humans but see dogs — fellow canids — as competition to territory and prey and will kill them if they perceive a threat.

Colorado's North Park pack has confirmed kills of three working cattle dogs and at least one pet dog.

Other Colorado wildlife pose more of a threat — albeit still remote — than wolves. According to Colorado Parks and Wildlife, since 1990, there have been 88 attacks by black bears on humans, three of which were fatal, and 28 attacks by mountain lions on humans, three of which were fatal. Since 2006, there have been 21 attacks by moose on humans, with one fatal attack, and nearly all occurred with a dog or dogs present.

What has/will it cost Colorado to bring wolves to the state and to compensate ranchers for livestock losses?

According to Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the state has spent $3.3 million over the past three years for planning and reintroducing wolves to Colorado. The agency allocated $2.1 million for reintroduction efforts in 2023-2024. The agency also paid $1 million for the environmental impact statement required under the National Environmental Policy Act to obtain the 10(j) rule, which allows lethal take of wolves in certain situations. This money comes from the state's general fund.

The ballot measure passed included compensation to livestock producers — up to $15,000 per animal as stated by the recovery plan — for loss to wolves. The state wildlife agency has paid ranchers nearly $40,000 over the last two years as compensation for the loss or injury to 14 cattle, three sheep and three working cattle dogs from the North Park pack. These funds do not come from hunting and fishing license fees but from separate funds, including Colorado Parks and Wildlife's species conservation trust fund and Colorado's nongame conservation and wildlife restoration cash fund.

Comparatively, in fiscal year 2022-23, Colorado Parks and Wildlife paid nearly $550,000 in compensation to livestock producers for 147 claims involving loss of livestock to black bears and mountain lions and elk eating crops and hay.

The state legislature has allocated the following money from the general fund to pay for livestock compensation due to wolf depredations: $175,000 for fiscal year 2023-24 and $350,000 and for each state fiscal year after that.

Starting Jan. 1, a "Born to be Wild" license plate was offered, with $50 of every specialty plate sold going to Colorado Parks and Wildlife's wildlife cash fund to pay for nonlethal control of wolves. For fiscal year 2023-24, a legislative bill authorizes up to $548,000 to be used by Colorado Parks and Wildlife to help livestock producers with nonlethal means to deter wolves.

A CSU study indicated those who voted for reintroduction would be willing to pay $31 million per year for 200 reintroduced wolves.

CSU created The Wolf Conflict Reduction fund to support the use of nonlethal tools for livestock producers through donations. Other nonprofit wolf advocacy organizations also have pledged financial help.

Here are rapid fire answers to other common wolf questions

Can you legally kill wolves in Colorado? They are listed as endangered and can only be killed if they are a threat to human life, in the act of killing livestock or when they are deemed to have chronically killed or injured livestock. Hunting of wolves is not allowed, and illegally killing a wolf can include a fine of up to $100,000 and jail time.

How many wolves can Colorado support? The state's minimum recovery goal is a sustained population of 150 to 200, but most studies indicate it could sustain more.

How successful are wolves at killing wild animals? They're successful killing elk and deer about 15% to 20% of the time.

What kills most wolves? Humans do through hunting, poaching, livestock depredation removal and collisions with vehicles. After that, in areas where other wolves are present, wolves killing other wolves over territory ranks high.

Do wolves kill for fun? Ranchers and hunters say yes, biologists say no. Sometimes, wolves eat only a portion of what is killed. Biologists say wolves might "surplus kill," meaning they kill more prey than they can immediately eat and sometimes return to eat it later.

Do wolves only kill the sick, old and injured? Wolves are opportunistic hunters. Biologists say a better explanation is they kill the vulnerable, which mostly are the sick, old and injured, but could also be a healthy cow elk made vulnerable when trapped in deep snow. The reason wolves opt for the most vulnerable is it reduces the risk of injury or death to the wolves.

Do wolves reduce the spread of chronic wasting disease in and vehicle crashes with deer and elk? Some, because they eat those animals, just like mountain lions do, but it is largely believed they don't play a significant role in either in most areas.

Did the reintroduction of wolves restore the Yellowstone National Park ecosystem and cause the drastic decline in elk numbers in the Greater Yellowstone Area and in central Idaho, as some claim? Just like wolves don't by themselves decimate deer and elk herds, neither do they single-handily restore ecosystems. In each case, they have played a part. Also in each case, some would have you believe that part is much larger than it actually was. Nature isn't that simple. Other ecological factors also have played a role in those events.

This article originally appeared on Fort Collins Coloradoan: Why Colorado's wolf reintroduction has caused such a big stir