After Nex's death, former LGBTQ+ students say Owasso has troubling history of bullying

OWASSO — Questions surrounding the final hours of a 16-year-old’s life in this suburban Tulsa city have sparked national scrutiny over the safety of transgender and gay children in Oklahoma.

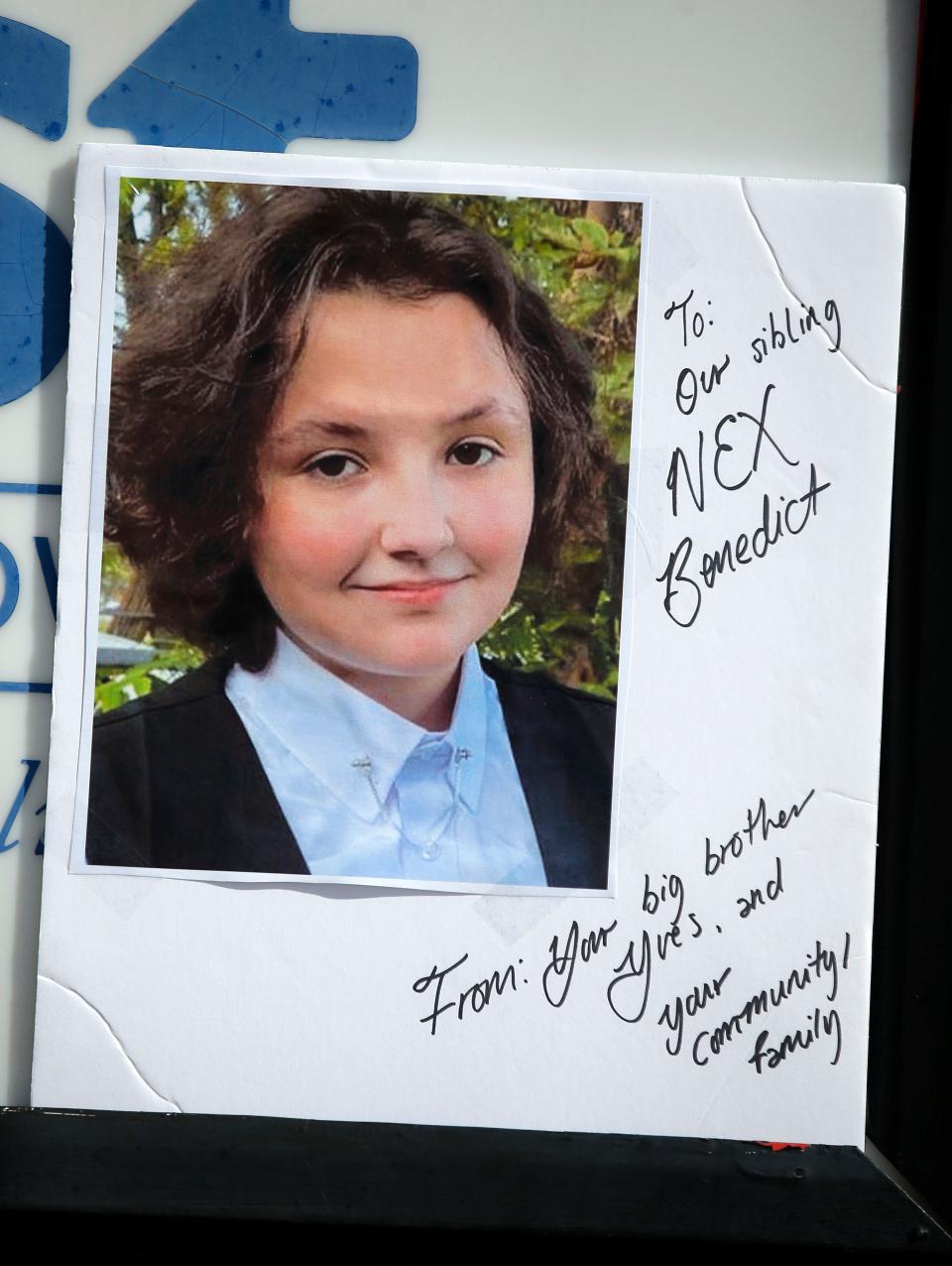

Nex Benedict died one day after an altercation inside an Owasso High School bathroom. Friends have said Nex, who used the pronouns they and them, had been bullied before over their gender identity, which was different from their gender at birth. Investigators are still interviewing the other students involved in the fight to determine whether Nex was targeted in an act of gender-based violence.

Police have said the teen did not die as a result of any injuries, citing initial autopsy results. But exactly what killed Nex remains unknown, nearly four weeks after they died.

For many across the United States, as demonstrated by a flood of posts on social media, the teen’s death has come to symbolize the dire consequences of anti-transgender rhetoric and laws being promulgated by several of the state’s elected officials.

A law passed in 2022 requires students to use restrooms that match the sex listed on their birth certificates. Critics fear a new proposal making its way through the Legislature could ban discussions about gender identities and sexuality entirely from schools. The state’s top schools official has called gender fluidity “the most radical concept we’ve ever come across in K-12 education.”

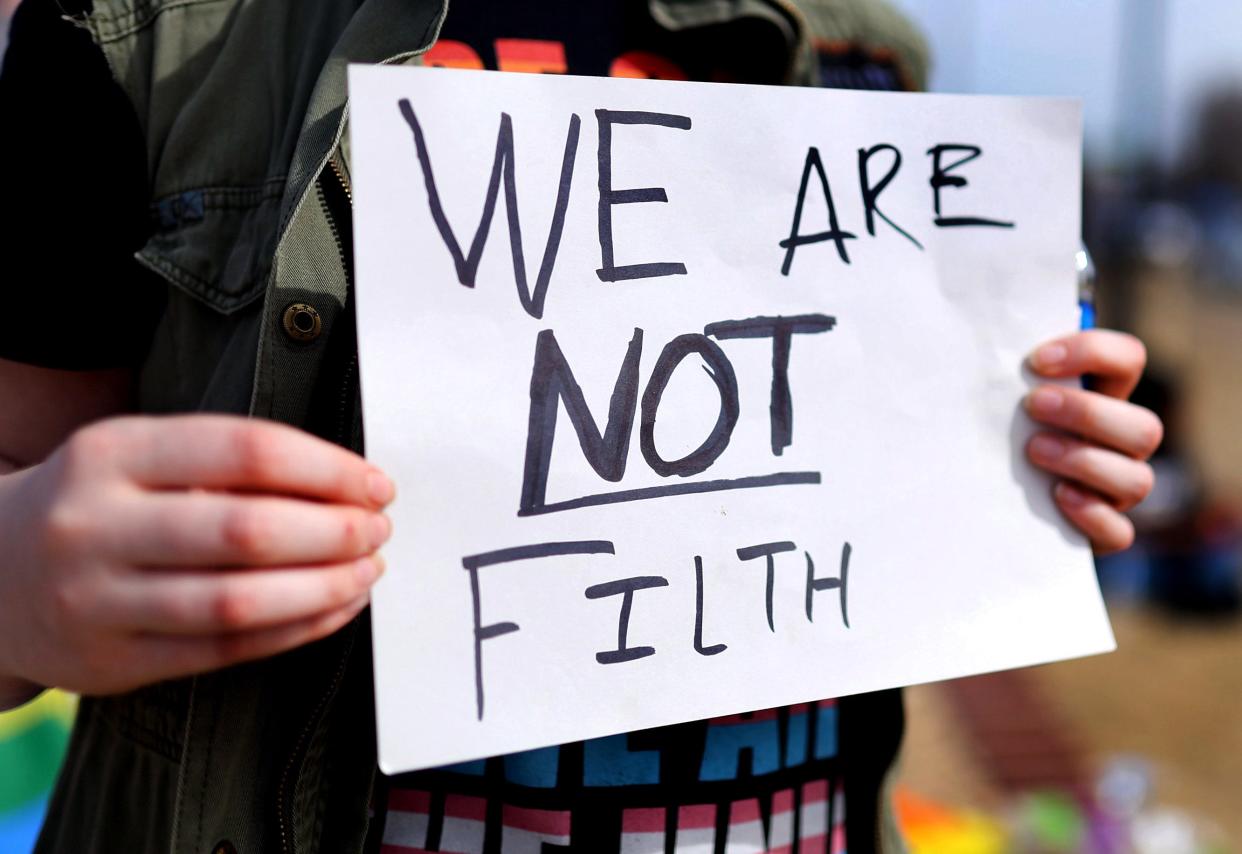

Editorial: Sen. Tom Woods' 'filth' comments expose Oklahoma's real moral crisis - LGBTQ+ kids are dying

'I was bullied pretty much every day, consistently'

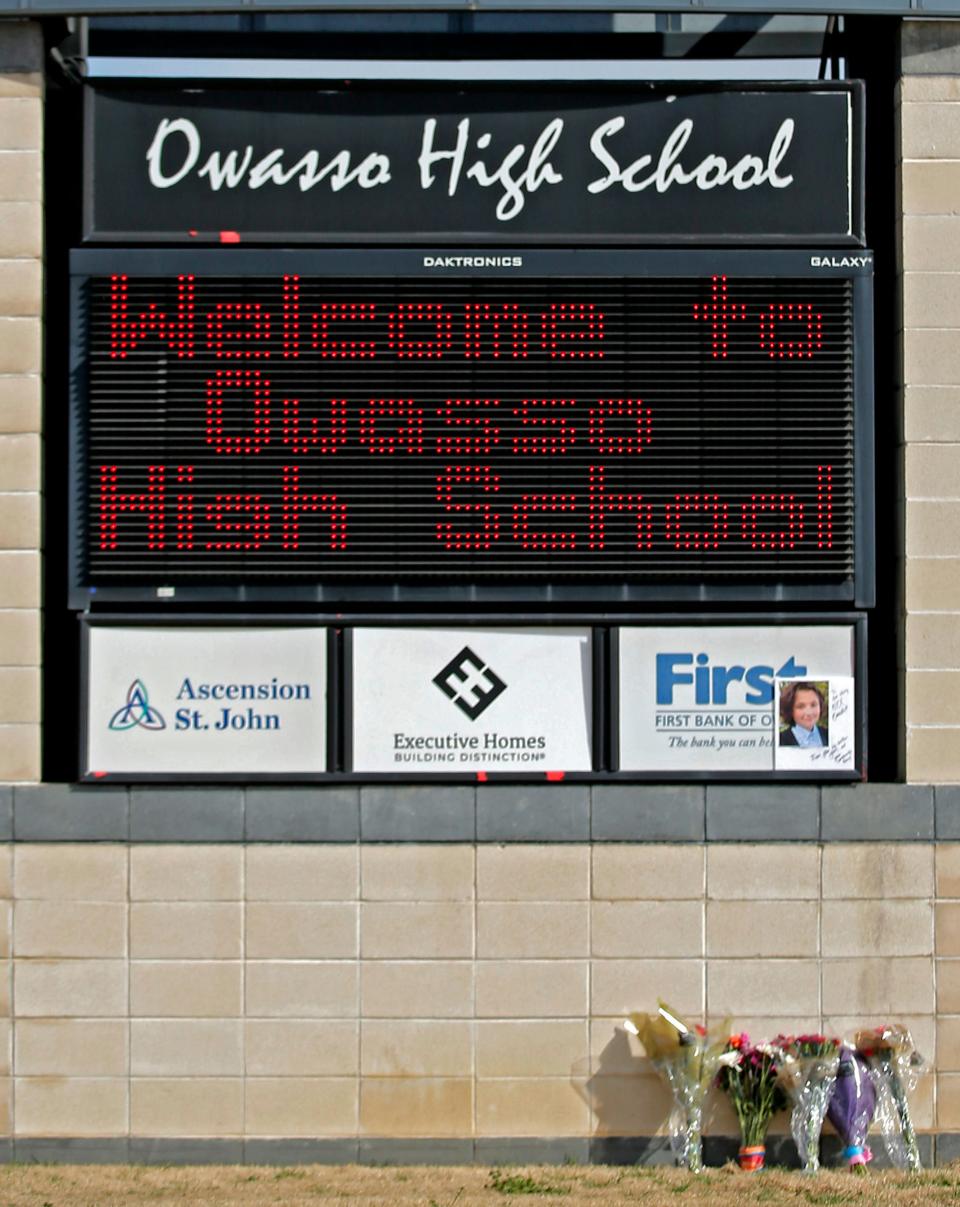

The groundswell of attention on Nex’s life and death has shined a bright light on Owasso and its public high school, where nearly 3,000 students attend classes. The city of about 40,000 residents has quickly transformed from a town with a few stop signs to a commuter hub that is a 15-minute drive north of Tulsa.

Several former and current Owasso students told The Oklahoman they recognized their own experiences in Nex’s story. They described instances of repeated bullying and harassment over their gender identities and sexualities and said they often felt administrators failed to appropriately intervene.

“I was bullied pretty much every day, consistently,” said Ren Stolas, 20, who is transgender. “That’s why this hurts a little extra.”

Yet others who live in Owasso don’t see the reckoning after Nex’s death as a hometown issue. They believe the furor will go away when a new cause takes hold on social media. Dozens of locals showed up at a recent rally in honor of Nex, not to join the demonstration but to watch it unfold from their cars and pickups. Some longtime residents believe the outrage has been manufactured by out-of-state advocacy groups that have seized on the tragedy of a child dying to spin a false narrative.

“I think people need to mind their own business and stay in their own lane,” said a downtown business owner, who asked not to be named over fears that some customers would stop coming in no matter what she said. “Leave us alone. This is a nice little town. You don’t need to muddy it up.”

Judy Jimison, a clerk at a downtown shop, echoed that sentiment.

“It’s the people from other towns that are coming in,” she said of the outrage.

More: The latest on the lawsuit against Ryan Walters over school pronoun rule

School administrators have issued statements expressing their condolences and making it clear they do not tolerate bullying.

No one representing the school spoke at a downtown candlelight vigil for Nex, which drew a few hundred people. A makeshift memorial for Nex on school grounds was mostly taken down in less than a day, though it's not clear by whom. Brock Crawford, a school spokesman, declined to say whether school officials had implemented any new anti-bullying measures in response to Nex’s death. He said administrators go over the school's anti-bulling policy with students at the start of every year and tell them how to report bullying.

Teachers and administrators rarely talk about bullying in class or in morning announcements, said Juan Pablo Alvarez, a 17-year-old senior.

“Honestly, I just wish they’d talk about bullying more, because it’s a prominent issue,” he said.

Friends remember Nex as fun-spirited and funny. Fiery and strong. Kind and thoughtful. They shared their memories with the crowd gathered at the downtown vigil, talking about how Nex was guarded but giving with close friends.

Some friends referred to Nex using the pronouns he and him. Relatives have said Nex also used the pronouns they and them. An obituary published by the family said Nex, a descendant of the Choctaw Nation, loved nature and cats, particularly their pet Zeus.

In a statement, Sue Benedict — Nex's grandmother whom Nex called Mom — acknowledged she was still learning about Nex's gender identity. “Please do not judge us as Nex was judged,” she said. “Please do not bully us for our ignorance on the subject.”

An attorney hired by the Benedict family said they wanted privacy to grieve and did not want to speak further. They plan to conduct their own investigation into the events leading up to Nex’s death.

In growing town, every teen ends up at Owasso High School

The family’s home sits in Owasso’s oldest residential neighborhood, sandwiched between a redeveloped downtown and a meat packing plant. Traffic driving toward Tulsa buzzes by on nearby U.S. 169.

Owasso did not extend far past the Benedicts' neighborhood for decades, until population booms in the 1970s and 2000s. Gated subdivisions on the outskirts of town are replacing the farms and ranches that once were Owasso’s main industry.

Even as the city grew, residents never embraced the idea of adding a second junior high or high school, so practically every teen who attends public school ends up at Owasso High. Marilyn Hinkle, who coordinates the city museum, remembers her son graduated from Owasso in 2000 in a class size of about 300. Graduating classes are closer to 700 or 800 students today.

The district has accommodated the growth in part by separating older grades into standalone buildings. Ninth- and 10th-graders like Nex go to West Campus, across the street from the other half of the high school and the football stadium.

What happened, according to body cam footage and reports

Nex and other students were stacking chairs after lunch on Feb. 7 before police and school officials say the altercation occurred. Security camera footage shows Nex walking into and out of a bathroom next to the cafeteria about the same time as several other students.

Nex later told a school resource officer a group of girls they did not know had been antagonizing them and their friends because of the way they dress and laugh. “So I went up there and I poured water on them, and then all three of them came at me,” Nex said, explaining the water came from a water bottle. Sue Benedict told the officer that Nex threw water on only one of the girls.

More: Owasso police release bodycam footage of Nex Benedict interview: ‘I got jumped’

The interview was recorded by the officer’s body camera. Nex said the girls took them to the ground and were beating them when Nex blacked out. Sue Benedict took Nex to a hospital to be checked out.

As Nex lay in the hospital bed, the officer explained Nex could also be facing assault charges because they squirted other students with water.

Nex was later released from the hospital. The next day, Feb. 8, Sue Benedict called 911 to report Nex was having trouble breathing. The teen died soon after.

The school the next day confirmed a student died, without disclosing their name or any details about what happened. The announcement gained little notice except from a few local news outlets that noted a student had died.

Days later, 2 News in Tulsa reported a fight had preceded Nex’s death, quoting an unnamed woman who also claimed Nex was targeted because of their gender identity. The story went viral after it was picked up by a LGBTQ+ news blog in Pennsylvania on Feb. 16.

School administrators went on to dispute many of the woman’s claims, including that Nex was so injured that they could not walk on their own. Police decided to release the body and security camera footage to try to tame the swell of online misinformation, said Lt. Nick Boatman, a spokesman for Owasso police.

But confusion and secrecy over other details — such as exactly how many students are under investigation — have continued to fuel widespread skepticism.

More: Search warrant filed in Nex Benedict death, police searched school records, bathroom

School spokesperson Jordan Korphage would not say whether administrators were aware of any past instances of Nex being bullied and, if so, what they had done to address the issue.

'I was not a threat, but I felt threatened'

Landon Wood said he felt Owasso school officials did little to protect him when he attended the school as a sophomore in 2018. Wood, 24, is transgender. He attended several public high schools in northeast Oklahoma and said his treatment at Owasso stands out as the worst.

He said he was once questioned by other students over the bathroom he was using. School administrators did not take steps to make sure teachers used his correct name, he said.

“You lose your privacy,” he said. “You never really get to let go of the person you were.”

Aren Deakins, who graduated from Owasso in 2018, said other students once cornered him and asked him to show his genitals. Deakins is queer and uses the pronouns he and it.

“I was not a threat, but I felt threatened,” he said, “and the school’s response was I could change lunch” times.

Crawford, the school district spokesman, did not speak directly to the experiences Wood, Deakins and other students described, but he said every report of bullying is investigated by the school.

"As a district, the safety and security of our students is our top priority, and we are committed to fostering a safe and inclusive environment for everyone," he said in an email. "Bullying in any form is unacceptable."

The growing number of anti-trans laws and policies have made it more confusing for children to navigate their rights at school, said Megan Lambert, the legal director for the ACLU in Oklahoma. “They retain the right to equal treatment before the law,” Lambert said. “That holds true regardless of any action of the state Legislature or state board of education.”

In addition to the bathroom ban law, state lawmakers also barred transgender girls and women from participating in female sports teams. The laws ignore trans children exist and are just trying to get through their school days like any other kid, Wood said. “We all have emotions,” he said. “We all have feelings.”

State schools Superintendent Ryan Walters has been the loudest supporter for the new laws and policies. “We’re not going to tolerate the woke Olympics in our schools, left-wing ideologues trying to push in this radical gender theory,” Walters said at a January meeting where the state Board of Education voted to require schools to get the board's approval before changing a student’s gender in official records.

That month he also appointed Chaya Raichik, an online personality who runs the far-right social media account Libs of Tik Tok, onto a state school library advisory board. In 2022, Raichik criticized videos posted to social media by an Owasso High School teacher, who said he was subsequently harassed and resigned from school.

The teacher, Tyler Wrynn, returned to Owasso to speak at the vigil for Nex. Wrynn said the teen loved to joke “'I’m going to fight you!',” always changing the reason why. One day it was over Wrynn’s sports car. Another day it was over being in Wrynn’s class.

“The world is a little darker because Nex is gone,” Wrynn said.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: After Nex's death, Owasso scrutinized over treatment of LGBTQ+ students