FAQ: Contested conventions and the Democrats' 'delegate math'

You may have heard some discussion lately about “delegate math” as it pertains to the Democratic presidential primary. And if you have, you might be wondering what this all means.

Here are the basics: Every time Democratic candidates do well in a primary or caucus, they win a share of delegates. The candidate who eventually wins 1,991 delegates, or a majority of the delegates in play, then becomes the Democratic nominee for president.

This is by no means a new process. But in most presidential primaries, the race for delegates is little more than a formality. After some number of primaries and caucuses, a clear front-runner for the nomination emerges and is considered the presumptive nominee by media outlets and party leaders. That candidate then appears at the party's convention the summer before the general election and is formally designated the party's presidential nominee.

This year, however, it's possible that none of the Democrats running for president will win a majority of delegates. And that means that the Democratic Party could be heading for a contested convention in Milwaukee this July.

More on that in a little bit. First, let's take a look at how this process works.

How do you win a delegate?

The mechanism by which a candidate wins a delegate is somewhat complicated and can vary from state to state. But generally speaking, a candidate needs to clear 15 percent of the vote in a given contest to start collecting delegates.

Once a candidate has cleared that 15 percent threshold, delegates are awarded based on how many people voted for that candidate and the other candidates who received at least 15 percent of the vote. Candidates also win delegates from winning at least 15 percent of the vote in various sections of the state, usually broken down by congressional district.

To put this at its simplest: The more votes a candidate receives in a given state or district, the more delegates they get.

What are these delegates supposed to do?

Once the primary results are in, delegates are pledged to a certain candidate and are expected to vote for that candidate on the first ballot of a convention. The first ballot is usually the only ballot, and the voting in that case is just a formality.

This is because everyone typically knows who the party's nominee is going to be long before the convention kicks off. The last time the Democrats had to go to a second ballot was 1952, when delegates chose Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson over Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver.

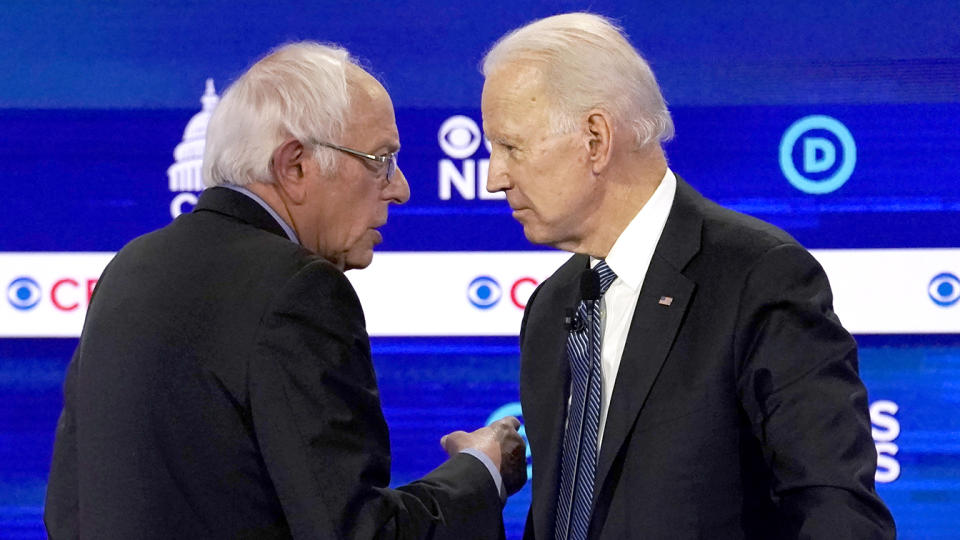

This year, however, it’s possible that neither Joe Biden nor Bernie Sanders will arrive at the convention with a majority of delegates. And it’s possible this could mean that there’s no winner on the first ballot and Democrats have to go to a second, which is when the so-called superdelegates enter the picture. More on them in a moment.

Do delegates have to vote for the candidate they're pledged to?

In theory, yes. In practice, there’s nothing anyone can really do to stop a delegate from voting for someone else.

Campaigns have some say in the people who become delegates for their candidate, and they don’t want to send anyone to the convention who might be disloyal.

But since it's been nearly 70 years since there was a truly contested convention, this could all get a little screwy. For example, the rules governing delegates aren't officially hammered out until the party’s rules committee meets in the days before the convention. And if Sanders and Biden both arrive at the convention with similar delegate totals, it’s possible the committee will try to make it easier or harder for delegates to switch from one candidate to another.

What about delegates pledged to a candidate who has already dropped out?

It’s not certain how this would all play out. After Biden's big South Carolina win, two candidates who had already won delegates — Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg — left the race and endorsed Biden. Mike Bloomberg did the same the day after Super Tuesday.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that the delegates pledged to Bloomberg, Buttigieg and Klobuchar need to follow suit. As with the Electoral College, which occasionally has an “unfaithful elector” vote for a candidate he or she wasn’t supposed to, there’s no real mechanism that prevents delegates from “going rogue.”

The best way to stop a delegate from defecting probably occurs when the delegates are themselves chosen. And while candidates don’t exactly get to pick their delegates, they do get a chance to review them. The actual picking, meanwhile, is mostly done by local parties after the voting has already occurred. So it’s a process that’s going on right now.

The political scientist Josh Putnam argues on his website, FrontloadingHQ, that because former candidates like Buttigieg and Klobuchar suspended their campaigns rather than ended them, they could still have some say in who their delegates will be. Otherwise, delegates are reallocated among the remaining candidates.

“But at the end, any reallocation isn't going to prove to be all that much of a boon to either candidate in the delegate count,” Putnam tweeted Friday. “Wooing the remaining district delegates from the candidates who dropped out might be … if the count remains close between Biden and Sanders.”

What about those superdelegates?

Due to rule changes after the 2016 election, superdelegates would only come into play on a second ballot, while in previous years they could vote on the first. So if there is a contested convention, superdelegates could be decisive.

Superdelegates are usually party elites: members of Congress, current and former Democratic National Committee officials and former presidents and vice presidents. There are 771 of them this year, and they aren't pledged to support anyone, although a recent New York Times report indicated that a substantial majority of them don't want Sanders to be the nominee.

The addition of 771 superdelegates on the second ballot means that a candidate would theoretically have to win 2,375 delegates to get to a majority.

July is still a long way off, so if either Sanders or Biden are able to rack up major wins in the remaining primaries, none of this may matter. But if Democratic primary voters deliver split decisions in the remaining contests, the party’s nominee might finally be selected by a small number of delegates.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: